In 1945 most European cities lay in ruins. But not all ruins were caused by bombings and not all destruction was material. Germany’s authoritarian regime disrupted the demography, traumatized societies for generations to come, and scarred the urban fabric even before the war began. As an example of this multifaceted destruction, this paper examines the defilement and subsequent demolition of the Bornplatz synagogue in Hamburg as well as the annihilation of Hamburg’s Jewish community during the Nazi regime. Currently, the reconstruction of the Bornplatz synagogue is being discussed with arguments revolving around questions of Jewish visibility and cultural manifestation in the contemporary city, as well as the memory of a lost identity. A reason for the controversy’s complexity is the multilayered character of the synagogue’s destruction in 1939: not only architectural but also symbolical and socio-demographical.

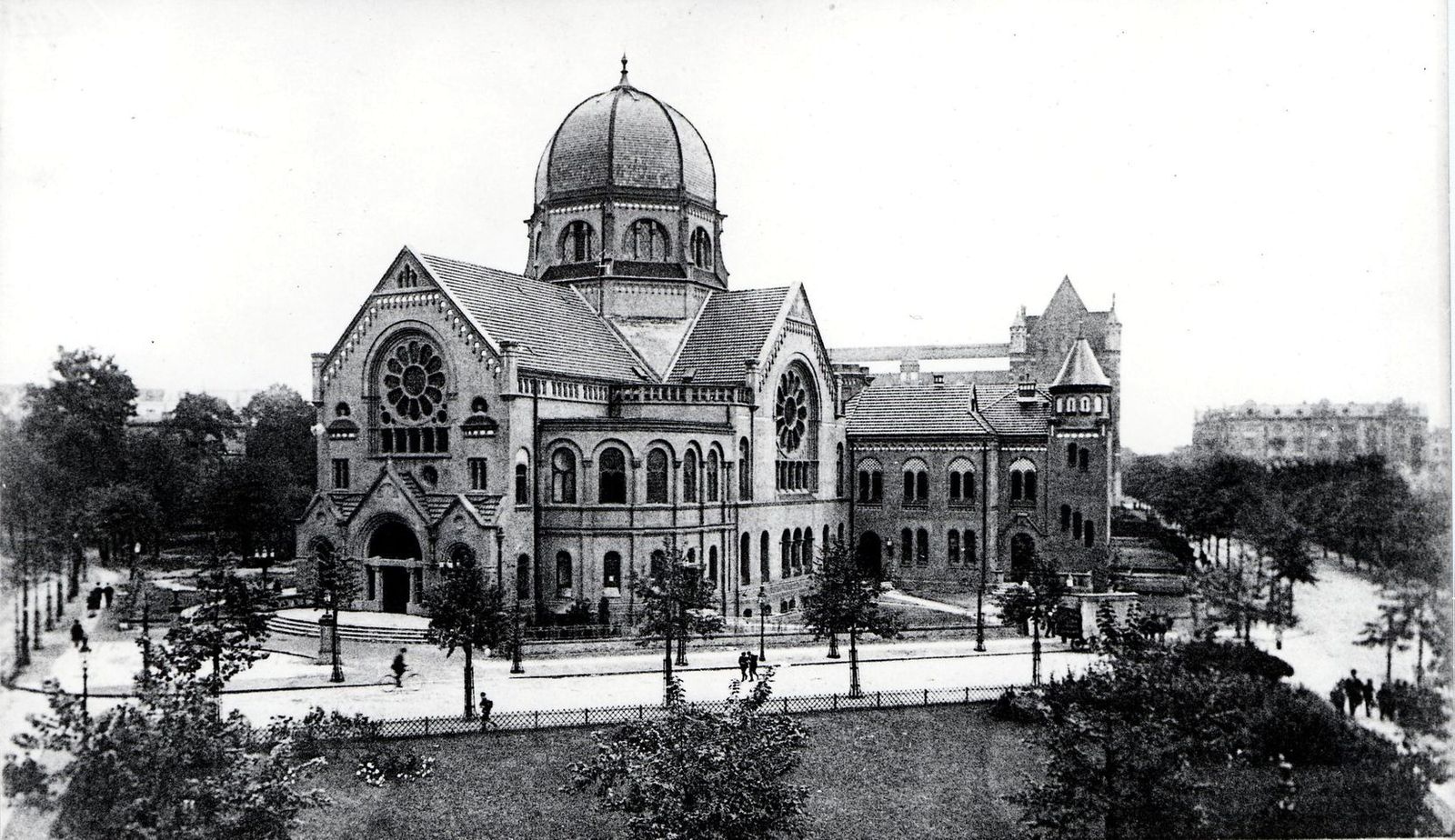

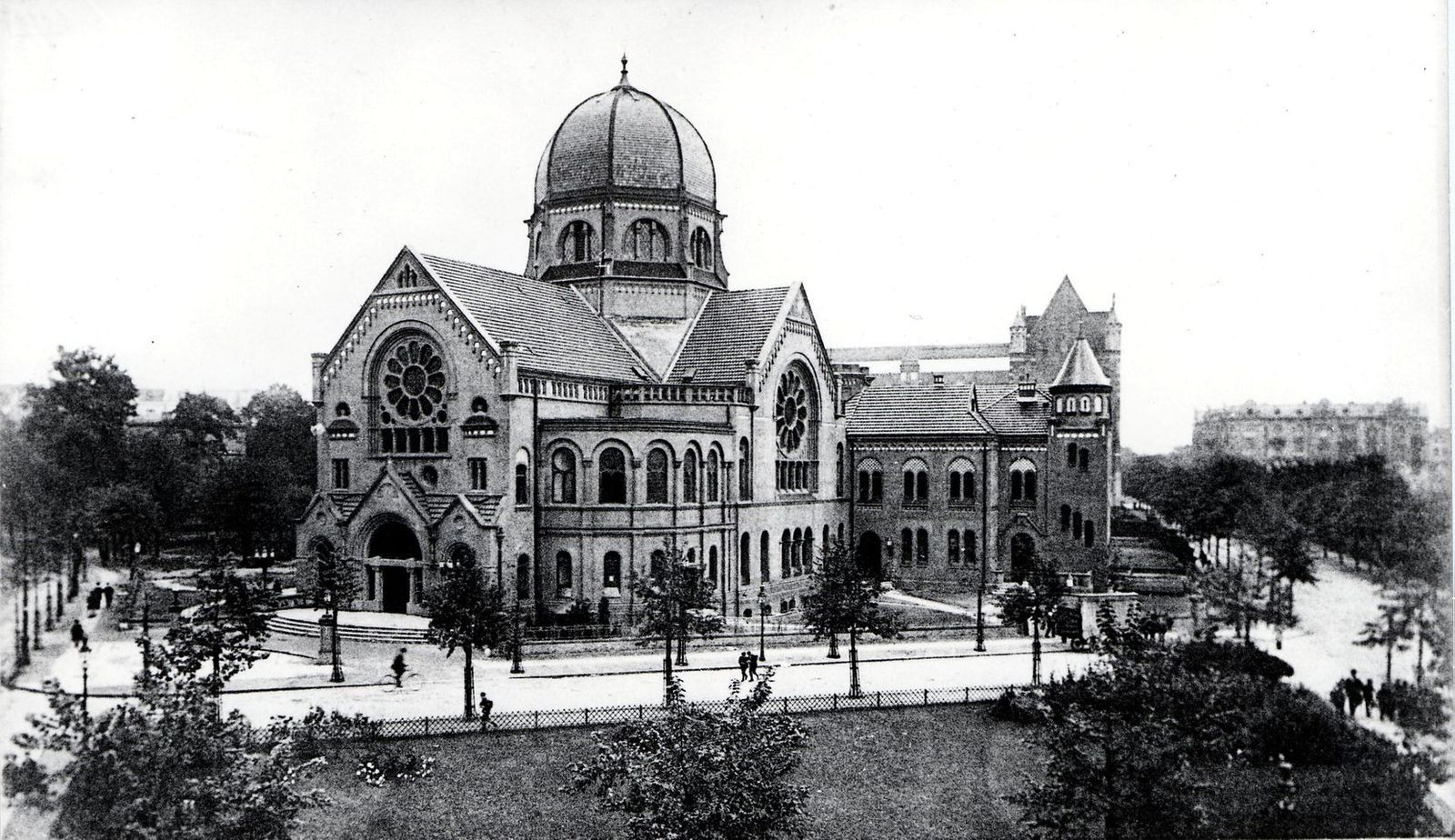

In 1906, the first detached synagogue in northern Germany was inaugurated on Hamburg’s Bornplatz at the heart of the then predominantly Jewish Grindel district. As an unmatched pinnacle for the city’s Jewish culture, the 1,200-seat synagogue was of major symbolic importance to the community. Only 32 years later, during the Reichspogromnacht, it was defiled by Nazi vandals and could no longer be used for services. The purchase contract from 1902 stated that the site had to be returned to the city if no longer used as a house of worship. In 1939 this clause enabled the Nazi administration to enforce the synagogue’s demolition and to repurchase the then-empty land. A high-rise bunker was built in one part of the site–the rest was used as a parking lot until the 1980s.

In this paper, I blur the edges between the architectural and the societal Stunde Null in post-war Europe. Exemplary of the destruction of both the Bornplatz synagogue and its community are investigated as are the succeeding difficulties of their rebuilding. My focus is the impact of these parallelly evolving histories of architectural and socio-cultural destruction and reconstruction on the collective identity and the architectural discourse in Hamburg.

In this article, I analyze the Bornplatz synagogue architecturally to elaborate on the effect its demolition had on society and the urban fabric. Furthermore, I introduce the Jewish community at the time of the synagogue’s construction and trail its fate beyond the historic fracture marked by the Holocaust. By portraying the demography of Hamburg’s Jewry since 1945 I contextualize the current debate, focusing on the longing of today’s Jewish community for a nonexistent continuity with a heritage that was never theirs.

The collective phantom pain caused by the destruction of the Bornplatz synagogue is exemplary of a non-canonical lost heritage. The complex impact of the destruction of the Second World War on German society has been the focus of the work of Aleida and Jan Assmann for decades1, the loss of Jewish heritage in the urban fabric is even harder to grasp. Partly, because for the second half of the 20th century, both the political narrative and individual memories negated the national socialist past2; and partly, because the direct victims of the destruction, most dead or exiled, were no longer part of German society. Basing my theoretic approach on Halbwachs’ definition of collective memory3, I argue that the Holocaust as a demographic fracture strongly impacts today’s debate on the reconstruction of the Bornplatz synagogue. After 1945, the former synagogue was voluntarily forgotten by the public and alternative urban narratives shaped the neighborhood’s collective memory. 50 years after its destruction the city4 turned the site into a memorial, thus shifting the discourse from forgetting to remembering. The site has since functioned as a lieu de memoire for the few decendants of Hamburg’s Jewish community before 19455. The heritage of today’s Jewish community in Hamburg is drastically different from the prewar one. This discontinuity in collective memory needs to be considered when the trauma caused by the destruction of the Bornplatz synagogue and the motivation for its reconstruction are analyzed. This article pursues the question of how the idea of a lost architectural heritage becomes a powerful strategy for creating a sense of belonging and unity. An important aspect of my argument is the symbolic importance of the synagogue to the community in the early 20th century in comparison to the community today.

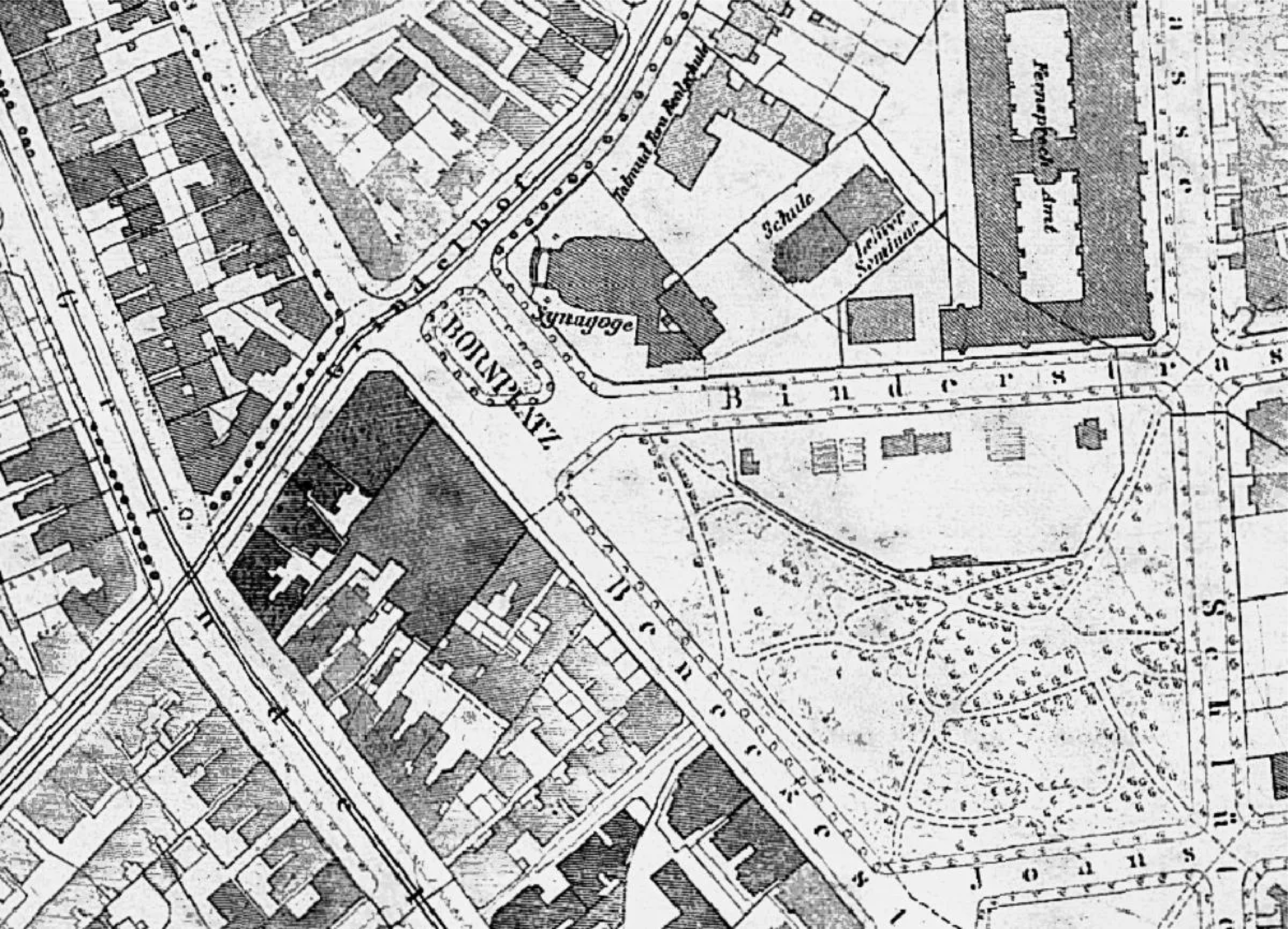

On January 10th, 1902, the head of the German Israelite Community (GIC) addressed the mayor of Hamburg in a letter, explaining the necessity for a new synagogue and asking to initiate the search for a suited site6. City and GIC soon agreed on a lot at the then northeastern side of the Bornplatz (fig. 1).

Only the GIC’s wish for a reduction in the price per square meter caused minor delays. The final contract had to be approved by the senate and the parliament that accepted the 50 percent markdown under one additional condition, forbidding the GIC to sell the plot to any third party or to use it for anything other than a place of worship7.

Already seven months before the amended contract was signed on December 10th, 1902, the Jewish architect Semmy Engel presented a first design proposal for the Bornplatz synagogue. However, it took several alterations and a scarcely documented architectural competition to finalize the plans which in the end were designed and realized in cooperation with a second Jewish architect: Ernst Friedheim8.

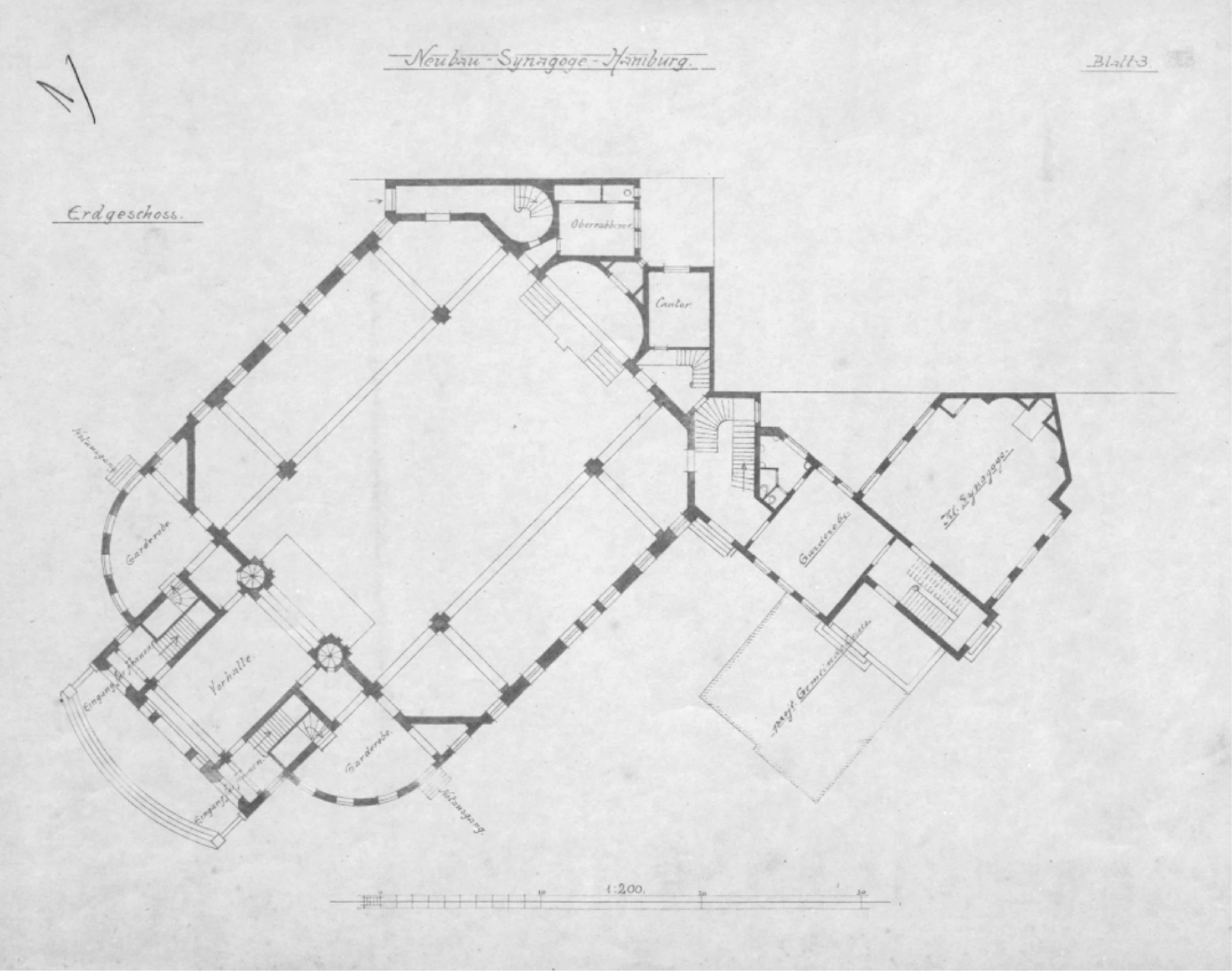

Construction broke ground on March 23rd, 19059. The synagogue was designed as a neo-Romanesque centralistic building with an east-westerly orientation. The main portal faced the western corner of the lot and thereby opened the synagogue towards both the square as well as the adjacent streets Grindelhof and Bornstraße10. The building was erected as a concrete structure with iron scaffolding and faced with ocher-colored brick masonry, as well as red sandstone and clinker details. The axisymmetric main building was supplemented on its right with a building wing containing community rooms, and offices, as well as a smaller prayer room for 100 people. A mikvah was situated in its basement, whereas the main synagogue’s basement housed the technical facilities as well as two apartments for staff.

From the main portal, male visitors reached the prayer room through a vestibule with coatrooms on both sides. Women entered the synagogue through two side entrances into stairwells that led up to screened-off galleries. Crossing the threshold of the square prayer room, one faced the Torah shrine located in an elevated apsis in the east. The latitudinal section evokes the feeling of naves guiding the viewer towards the shrine. However, the lateral naves were topped with the women’s galleries (fig. 2).

One of the few interior photos (fig. 3) shows the prayer room with rows of benches facing the Torah shrine. Plan and exterior photos suggest a centrality of the building, with the almemar centered underneath the rib-vaulted dome (figg. 4 and 5). The interior dome was only half of the height of the external 39-meter-tall cupola.

This elevated cupola, visible from afar, exemplified the synagogue’s importance to the Jewish community in Hamburg. This is also stressed in the description of the synagogue’s inauguration by a touched journalist in the local newspaper on September 14th, 1906. He stated that “the illuminated house of God shining bright with lights, gave an imposing sight”11 and closed his report of the festivities by paraphrasing the rabbi:

After emphasizing the importance of the house of worship, he concluded with the wish that the synagogue may be a beautification to the patrial city and forever a blessing to the community12.

The monumental synagogue at the center of the vibrant Jewish Grindel district had such an immense symbolic meaning to the Jewish community for three reasons: Firstly, it was unprecedented in visibility. In northern Germany, all former Judaic places of worship were either located in courtyards or their facades were interchangeable with those of the neighboring edifices. This had been due to the historic need to protect Jewish structures from antisemitic aggression as well as to the late legal equality for Hamburg’s Jewry13.

Secondly, by having the same urban features as a cathedral, the synagogue became a landmark and the Bornplatz developed into the cultural core of the growing Jewish neighborhood. It hereby epitomized the significant improvement of the situation of the Jewish population since 1860. With the unification of Germany under the Prussian emperor, Jewish culture flourished in Hamburg for the first time since the Napoleonic occupation in 1811-1814. This demographic shift towards a growing Jewish middle class was especially visible in the newly constructed residential areas outside of the former city gate Dammtor. Whereas in 1870, 75 percent of the Jewish population lived in the poor quarters of the Alt- and Neustadt, 50 years later 70 percent lived in the neighborhoods Havesterhude, Grindel, and Eimsbüttel14. The construction of a central synagogue represented not only the growing wealth of the Judaic populace but more importantly their optimism for a better future in the German Empire.

This confidence also manifested itself in the synagogue’s stylistic features. Most Jews in 19th-century Hamburg were patriotic Germans15. During an age of increasing nationalism, and architecturally dominated by the ideas of historicism, it became a fundamental task to find a suitable architectural heritage for German synagogues.

Gottfried Semper’s so-called Semper Synagogue in Dresden, which was consecrated in 1840, is often named as the one inspiring Engel for the Bornplatz synagogue16. Semper’s synagogue has been a frequently cited example for curiously both the positions taken in a dichotomous discourse on Jewish historicism17. One group turned to the oriental roots of Jewry: The interior of the synagogue in Dresden showed Moorish and Byzantine motives. Their opponents worried that orientalistic motives would needlessly alienate the Jewish minority from their Christian neighbors. Instead, they argued for a Romanesque revival which the plan and exterior elevations of Semper’s design are prototypical of. Hamburg’s prominent example of the neo-Romanesque style was the Bornplatz synagogue, hence, making it an important symbol for the Jewish self-identity as part of German culture18.

The emblematic importance of the Bornplatz synagogue for Jewish culture only intensified with the rise of the national socialists and the increase of antisemitic aggression in Germany. As a member of the community claimed:

Almost nothing has remained for us in these days but our synagogue. It has become our spiritual home and the place where our entire religious and cultural life takes place19.

The devotion to their house of worship was economically expressed in 1938 when the GIC renovated the interior of the synagogue20. That same year, during the Reichspogromnacht on the night of November 9th a pseudo-spontaneous act of Nazi vandalism destroyed synagogues all over Germany. The freshly refurbished Bornplatz synagogue suffered only minor damages caused by two fires. However, repairs were needed before the defiled synagogue could have been reopened for spiritual service21. This interruption of the synagogue’s usage as a place of worship was exploited by the officials who referred to the amended purchase contract from 1902. Leo Lippmann, head of the GIC’s last board of directors, surrendered to the national socialists’ line of argument. Since all legal autonomy was lost when the dissolution of the GIC was enforced in December 1938, Lippmann’s priorities were financial damage control as well as the salvation of sacred objects22. The lot at the Bornplatz was repurchased by the city on May 2nd, 1939. The demolition of the synagogue began only a few days later23.

The actual ruination of the Bornplatz synagogue did not take place during the Reichspogromnacht, but months later in the form of a planned and legally justified destruction. The demolition of the Bornplatz synagogue cannot be justified by the immediate damages caused in the morning hours of November 10th. Instead, it was a deliberate act by the national socialist government to obliterate Jewish heritage.

Even before the demolition started the city ordered for the building material to be orderly stored on site for later purposes24. A few months after the demolition was completed the urban composition of the Grindel district was substantially altered. In 1940, construction for one of Hamburg’s first high-rise bunkers began. Instead of on the site of the former synagogue, the bunker was mostly positioned on the square itself, thereby dividing the former Bornplatz into what is today the Allende Platz in the south-west and the Joseph-Carlebach Platz in the north-east.

From the socio-architectural aspects described above, I will now shift the focus towards the societal situation of Hamburg’s Jewry. The rise of the national socialists in Germany marked the end of the short period of Judeo-cultural prosperity. Jewish life in Hamburg until the late 19th century was dominated by antisemitism and legal inequality. Especially within the city, the Jewish minority was suffering from residency- and labor restrictions25.

During the French occupation in 1812, the GIC was founded as an institutional umbrella for all three of Hamburg’s groups of Jewish faith. With its 6,300 members, the GIC became Germany’s largest Judaic union26. It however took another century to arrive at the Jewish self-identity depicted previously. The Hanseatic city of Hamburg only granted Jewish men the right to become citizens and to vote in 1860. During the Weimar Republic at the height of the roughly 70 years of cultural flourishment, the GIC counted 20,000 members. The Grindel district became a vibrant hub for Jewish life and culture. Kosher stores, cultural clubs, theaters, and cafés lined the streets around the Bornplatz synagogue27.

The community’s steady growth and socioeconomic success as well as the general optimism at the time manifested themselves architecturally in the synagogue. Especially the following excerpt of a poem, published for the inauguration of the Bornplatz synagogue, highlights the pride and patriotism of the people:

At a time when in the neighboring land

The houses of our brothers are scorched and exploded;

Where hundreds by assassin’s strokes

Are slaughtered, thousands harassed.

Where oh so many are cheated of their fortune

And robbed of their life’s highest good;

Where even synagogues are reviled and plundered,

And tormented, stoned, those who believed in God.

At this time here in German lands,

In Hamburg, our dear father city,

A new, beautiful house of God has risen,

Which the congregation has erected28.

Retrospectively, these words filled with enthusiasm for the German nation are hard to read aloofly, knowing that 29 years later almost to the day the Nuremberg Laws deprived all Jews of their German citizenship.

The horrifying rationality and efficiency of the national socialists’ persecution of Jews will not be the focus of this article. However, several numbers need to be mentioned to understand the magnitude of sociodemographic change Hamburg’s Jewry underwent during the past 100 years. Apart from the millions killed in the Holocaust; antisemitism, legal discrimination, and other limitations of the mundane provoked grave waves of Judaic emigration.

In 1926, the GIC had 20.749 members, by 1940, less than 2,000 Jews were registered in Hamburg, and after the war, on July 8th, 1945, twelve of 80 surviving Jews in the city gathered to institutionally found a new Jewish Community29. As these mortifying numbers demonstrate, architectural reconstruction was neither an immediate priority nor a possibility.

Instead, the main motivation for the re-establishment of a Jewish Community was an attempt for legal continuity with the original GIC to facilitate later restitution30 . However, the small Jewish community rivaled the GIC’s legal succession with a British organization coordinating the compensation of Jewish property taken or damaged by the national socialists. In the Britishly governed Hamburg, the Jewish Trust Cooperation (JTC) focused its efforts on collecting funds for the newly founded state of Israel where many of the heirs had migrated to. To most, the thought of rebuilding Judaism in Germany seemed unrealistic, which is why the demands of the JTC dominated the negotiations and the majority of the financial compensations never reached the Jews that remained in Hamburg31. In 1951, the restitution case for the Bornpatz synagogue was opened. Initial negotiations between the JTC and the city failed due to drastically divergent price expectations. To accelerate the payment, a lump sum agreement of 1,500,000 Mark for twelve formerly Jewish lots was signed in 1954. The site of the Bornplatz synagogue belonged to the Hanseatic city of Hamburg until 202332. Legally and practically, the GIC had ceased to exist by the end of the war.

Hamburg’s Jewry remained without a new synagogue until 1960. Located in a residential area, the synagogue Hohe Weide is exemplary for many post-war synagogues in Germany. Despite the attempts of denazification, for the most part, Germany was still operated by the same staff as during the national socialist regime. The decentrality of the new synagogue derived from the heteronomy of these defectors. Other than hampering the restitution payments, officials with continuous careers often aimed to banish Jewry out of sight33.

Like many other German sites of former synagogues, the empty square next to the high-rise bunker was destined to be forgotten by the general public. Used as a parking lot, the grounds of the Bornplatz synagogue were only reacknowledged by officials in the 1980s34. On the 50th anniversary of the Reichspogromnacht, a floor mosaic by the artist Margit Kahl was inaugurated (fig. 6).

It depicts the ceiling plan of the destroyed synagogue on the otherwise empty square35. A lieu de memoire for some, today the square is predominantly used as a shortcut for students hurrying towards the contiguous university.

For Germany’s Jewry, the most important demographic turning point since the holocaust was the collapse of the USSR. Due to the significant number of formerly Soviet Jews migrating to Hamburg, the 1990s marked the first substantial increase of members for the Jewish Community Hamburg (JCH). Today the JCH has 2,300 members, predominantly with an Eastern European heritage36.

Since the early 2000s, the needs of the JCH have shifted. The Talmud Tora school, formerly adjacent to the Bornplatz synagogue, was regifted by the city to the JCH in 2002, making this an important precedent case for today’s debate. Other than acknowledging the insufficiency of the reparations paid in the 1950s, this was a first step in moving the center of Jewish life in Hamburg back to the Grindel district.

An increase in antisemite activity throughout Germany has intensified the discussions on Judaic visibility and its place in German society. Especially the attack on the Synagogue in Halle in 2019 fueled both: the demand for a more openly celebrated Judaism as well as security concerns. In the case of the JCH, the enhanced exposure posed the opportunity to address the wish to reconstruct the Bornplatz synagogue. While growing antisemitism might explain the wish for a centrally located and prominent synagogue, the call for a reconstruction of the demolished neo-Romanesque building caused a multi-faceted debate.

Reconstructions of Prussian monuments in Germany are often interpreted as a sign of nostalgia for a national identity predating the collective guilt of the Holocaust. However, it would be absurd to accuse the JCH of denying the annihilation of Jewish culture. Nonetheless, there has been strong critique against the intended erasure of the memorial by Margit Kahl. Erika Estis was one of the Holocaust survivors who found emotional words against the reconstruction:

The attempt to replicate that old synagogue is despicable and the destruction of the entire memorial to a former time is heartbreaking to those of us whose families lived, worshipped there, and were exterminated. […] I understand that people like me don’t live in Hamburg anymore but the newcomers must respect our former culture, our history, and anything else is unacceptable37.

As Estis is one of the few living members of the original GIC, her open letter is an important source for the experienced distinction between the GIC and the JCH. By negating a shared heritage, this letter stresses the ambivalence in the current debate between honoring past injustice and allowing future generations to prosper.

The prominent Bornplatz synagogue of 1906 stood for the belief in a better future, today its reconstruction is wished to do the same. However, the original building of the Bornplatz synagogue does not comply with contemporary requirements. The JCH’s wish to reconstruct the Bornplatz synagogue is multilayered and needs to be discussed as such. Primarily the JCH desires an upgrade of their built infrastructure in the form of a cultural center as well as a new synagogue38. Secondly, Jewish culture should no longer be banned to the periphery especially since the Talmud Tora school has been shifting the Judeo-cultural core back to the Grindel district. The idea of architectural reconstruction appears to be an attempt to justify the project at the historic location.

As previously mentioned, in the German architectural heritage discourse, the intention of conservative reconstruction is often associated with the desire to retrospectively build a “better past”. The JCH is arguing that they wish to reconstruct the synagogue to build a better future. I have aimed to contextualize the community and the building of the original Bornplatz synagogue, to illustrate the demographic fracture that took place in the 20th century. The current debate shows the JCH’s urge to legitimize their presence in the Grindel district by reviving anachronistic architecture. The idea of the lost heritage becomes more powerful than the actual edifice itself. However, analyzing the current debate with Arendt’s thoughts on the discursivity of society, only public discourse can create a city’s heritage39. Even if, as elaborated above, the GIC and the JCH share little commonalities, the debate itself resuscitated Jewish heritage in the Grindel district. The Bornplatz synagogue was then and is again a powerful symbol for a better Jewish future in Hamburg.

notes

Assmann, Aleida, and Ute Frevert. 1999. Geschichtsvergessenheit - Geschichtsversessenheit: Vom Umgang Mit Deutschen Vergangenheiten Nach 1945. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt; Assmann, Jan. 2011. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press.

For a focused overview of important turning points in German heritage construction see: Jaeger, Susanne. 2012. “Interrupted Histories: Collective Memory and Architectural Heritage in Germany 1933–1945–1989.” In Heritage, Ideology, and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Matthew Rampley, 1st ed., 67–92. Boydell and Brewer Limited.

Halbwachs, Maurice. 1967. Das Kollektive Gedächtnis. Stuttgart: Enke.

The “free and Hanseatic city of Hamburg” has been and still is today a city-state with its own constitution. Therefore, the terms “state” and “city” can be used interchangeably in this context.

Nora, Pierre. 1990. Zwischen Geschichte und Gedächtnis. Kleine kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Band 16. Berlin: Verlag Klaus Wagenbach.

Letter by Levin Lion from 10.01.1902, fond 311-2IV, signature 7072, STAHam.

Purchase contract from 10.12.1902, Anlage No. 18 der Mittheilungen des Senats an die Bürgerschaft vom 23.01.1903, fond 311-2IV, signature 7072, STAHam.

Rohde, Saskia. 1991. “Synagogen im Hamburger Raum 1680 - 1943.” In Die Juden in Hamburg 1590 bis 1990. Wissenschaftliche Beiträge der Universität Hamburg zur Ausstellung “Vierhundert Jahre Juden in Hamburg,” edited by Arno Herzig, 159, Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz.

Hamburgische Nachrichten from 24.03.1905, fond 731-8, signature A680 Gemeindesynagoge am Bornplatz, STAHam.

Engel’s original proposal ignored the traditional orientation of synagogues towards the east and positioned the main portal perpendicular to the square, disregarding the legally binding setback lines. The city rejected this first proposal which resulted in the diagonal placement within the urban layout (Bericht der Bau-Deputation from 30.06.1902 and Skizze zu einer Synagoge am Bornplatz, fond 311-2IV, signature 7072, STAHam).

“Das lichtgefüllte, im hellen Lichterglanz erstrahlende Gotteshaus gewährte einen imposanten Anblick.“ All translations are by the author unless indicated otherwise.

“Nachdem er die Bedeutung des Gotteshauses betont hatte, schloß er mit dem Wunsche, daß die Synagoge der Vaterstadt zur Zierde, der Gemeinde stets zum Segen gereichen möge” (Hamburgische Nachrichten from 14.09.1996, fond 731-8, signature A680 Gemeindesynagoge am Bornplatz, STAHam).

Cohen, Martin. 1930. “Ein Streifzug durch die Deutschen Großgemeinden. Hamburg.” Israelitisches Familienblatt, 1930.

Lorenz, Ina. 2005b. “Die Jüdische Gemeinde Hamburg 1860 – 1943 Kaiserreich – Weimarer Republik - NS-Staat.” In Zerstörte Geschichte: Vierhundert Jahre Jüdisches Leben in Hamburg, edited by Ina Lorenz, 135. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung.

Herzig, Arno. 1991. Die Juden in Hamburg: 1590 Bis 1990 ; Wissenschaftliche Beiträge Der Universität Hamburg Zur Ausstellung “Vierhundert Jahre Juden in Hamburg.” Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz, 25.

Although, no personal records by the architect can be found to prove this.

For more detail on the provenance of Semper's stylistic choices see: Giese, Francine, and Ariane Varela Braga, eds. 2018. The Power of Symbols. Peter Lang AG: Lausanne.

Wischnitzer, Rachel. 1964. The Architecture of the European Synagogue. Philadelphia, Pa.: Jewish Publishing Society, xxix; Hammer-Schenk, Harold. 1981. Synagogen in Deutschland: Geschichte einer Baugattung im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert, (1780-1933). Hamburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Juden, Bd. 8. Hamburg: H. Christians, 233; Krinsky, Carol Herselle. 1988. Europas Synagogen: Architektur, Geschichte und Bedeutung. Stuttgart: Dt. Verl.-Anst, 28.

“Uns ist in diesen Tagen fast nichts geblieben als unsere Synagoge. Sie ist uns unsere seelische Heimat geworden und der Ort, an dem sich unser ganzes geistiges und kulturelles Leben abspielt” (quoted by Stein, Irmgard. 1984. Jüdische Baudenkmäler in Hamburg. Hamburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Juden. Hamburg: Christians, 80).

Baupolizeiliches Protocoll, fond 324-1, signature K2928, STAHam.

Negotiations between Leo Lippman and the city, fond 311-2IV, signature 2646, STAHam.

Lorenz, Ina 1994. “Juden in Hamburg 1941 Und 1942 - Die Sogenannten Lippmann-Berichte.” Aschkenas 4; 2005a. “Aussichtsloses Bemühen: Die Arbeit der Jüdischen Gemeinde 1941 bis 1945.” In Zerstörte Geschichte: Vierhundert Jahre Jüdisches Leben in Hamburg, edited by Ina Lorenz. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung.

Fond 311-2IV, signature 2646, STAHam.

Notiz der Bauverwaltung Tiefbauamt vom 28.03.1939, fond 311-2IV, signature 2646, STAHam.

The international importance of the Hanseatic port resulted in several Jewish families being looked upon favorably by the senate, due to their international connections and wealth. Families such as Heine, Warburg, or Ballin provided influential members of society. Nevertheless, their success was the exception. See Freimark et al. (Freimark, Peter, Institut für die Geschichte der Deutschen Juden (Germany), Gesellschaft für Christlich-Jüdische Zusammenarbeit (Germany), and Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, eds. 1983. Juden in Preussen, Juden in Hamburg. Hamburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Juden, Bd. 10. Hamburg: Christians.) for a detailed chronology of Hamburg’s Jewry. Freimark, Peter. 1991. “Innerhalb des Deutschen Judentums hatten Die hamburger Juden ein eigenes Profil.” In Spuren der Vergangenheit sichtbar machen: Beiträge zur Geschichte der Juden in Hamburg, edited by Peter Freimark, 3. Aufl. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung : Institut für die Geschichte der Deutschen Juden; Heinsohn, Kirsten, and Institut für die Geschichte der Deutschen Juden, eds. 2006. Das Jüdische Hamburg: ein historisches Nachschlagewerk. Göttingen: Wallstein; Marwedel, Günter. 2005. “Die Aschkenasischen Juden Im Hamburger Raum (Bis 1780).” In Zerstörte Geschichte: Vierhundert Jahre Jüdisches Leben in Hamburg, edited by Ina Lorenz. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung.

Lorenz, Ina. 2005b. Op. cit., 134.

Lorenz, Ina. 1987. Die Juden in Hamburg zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik: Eine Dokumentation. Hamburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der Deutschen Juden, Bd. 13. Hamburg: H. Christians; 2005b; Ophir, Baruch Z. 1991. “Zur Geschichte Der Hamburger Juden 1919-1939.” In Spuren der Vergangenheit sichtbar machen: Beiträge zur Geschichte der Juden in Hamburg, edited by Peter Freimark, Hamburg: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung : Institut für die Geschichte der Deutschen Juden.

“Zu einer Zeit, wo man im Nachbarreiche / Die Häuser unsrer Brüder sengt und sprengt; / Wo Hunderte durch Meuchelmörderstreiche / Man niedermetzelt, Tausende bedrängt. / Wo ach so viele um ihr Glück betrogen / Und ihres Lebens höchsten Guts beraubt; / Wo man selbst schmäht und plündert Synagogen, / Und peinigt, steinigt, die an Gott geglaubt. / Zu dieser Zeit ist hier in deutschen Landen, / In Hamburg, unserer teuren Vaterstadt, / Ein neues, schönes Gotteshaus erstanden, / Das die Gemeinde sich errichtet hat”. (Zur Einweihung der neuen Gemeindesynagoge am Bornplatz. Hamburg d. 13.09.1906, fond 731-8, signature A680 Gemeindesynagoge am Bornplatz, STAHam).

Lorenz, Ina. 2005b. Op. cit., 145.

Heinsohn and Institut für die Geschichte der Deutschen Juden 2006.

Lorenz, Ina, and Jörg Berkemann. 1995. Streitfall Jüdischer Friedhof Ottensen. [1], Wie lange dauert Ewigkeit: Chronik. Hamburg: Studien Zur Jüdischen Geschichte 1; Schreiber, Ruth. 1997. “New Jewish Communities in Germany after World War II and the Successor Organizations in the Western Zones.” Journal of Israeli History 18 (2–3): 167-190.

As this paper is written, on September 23, 2023, the Parliament voted to transfer the property to the JCH without cost (Bürgerschaft der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg 2023. Drucksache 22/12944). Fond 311-2IV, signature 2647, STAHam.

Klei, Alexandra. 2018. “Jüdisches Bauen in Nachkriegsdeutschland: Möglichkeiten und Bedingungen.” In Architektur und Akteure, edited by Regine Heß, 43:161–74. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 168.

Hamburger Abendblatt from 11.02.1982, fond 731-8, signature A680 Gemeindesynagoge am Bornplatz, STAHam.

Die Welt from 11.09.1988, fond 731-8, signature A680 Gemeindesynagoge am Bornplatz, STAHam.

Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland. n.d. “Jüdische Gemeinde Hamburg KdöR.” Accessed September 1st, 2023. https://www.zentralratderjuden.de/vor-ort/gemeinden/projekt/juedische-gemeinde-hamburg-kdoer/.

Estis, 2021. “Auszüge aus Briefen von Erika Estis und Ofra Givon.” Accessed August 13th, 2023. https://www.patriotische-gesellschaft.de/de/unsere-arbeit/stadt/bornplatz-synagoge.html.

Wandel Lorch Götze Wach. 2022. “Wiederaufbau Bornplatzsynagoge Hamburg”.

Arendt, Hannah. 1960. Vita activa oder Vom tätigen Leben. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Lorenzo Mingardi (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Tom Avermaete Leonardo Zuccaro Marchi

Luigiemanuele Amabile Alberto Calderoni

Lorenzo Grieco