The Brazilian modern architecture, originally envisaged as a project of social emancipation, underwent a profound transformation over the decades. This paper investigates how political and economic changes - particularly following the 1964 military dictatorship in Brazil -weakened the social role of architectural design, promoting the elitization of urban space and the marginalization of metropolitan peripheries, notably in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. It dialogues with Vilanova Artigas’s theory of the “social function of architecture”, Oriol Bohigas’s critique of “architecture as consumption”, and Ermínia Maricato’s and Pedro Arantes’s reflections on the crisis of modernism in Brazil during the dictatorship years. After the 1964 coup, the persecution of progressive architects, democratic suppression, and the forces of capital reproduction deepened urban segregation, restricting access to architectural projects and encouraging self-construction in favelas and suburban areas, promoting peripheralization. This exclusionary logic has resonated globally, due to the weakening of public housing policies. It is concluded that architecture must be reappraised as a tool for social justice, advocating for the right to architectural design within public policy. Alternative models - such as those practiced by the Usina de Arquitetura collective - are presented as potential (though to be radicalized) solutions to combat structural inequalities and promote urban inclusion, moving beyond generic housing programs that overlook community needs and become new agents of segregation.

This paper examines the evolution of Brazilian modern architecture, originally conceived as a project of social emancipation, and how it gradually became an instrument of urban segregation, particularly in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Drawing on autobiographical and ethnographic insights, the authors - raised in peripheral areas of these cities - reflect on the dismantling of the utopian promises of modern architecture by the political and social crisis resulting from the political rupture caused by the 1964 military coup.

Modern architects such as Afonso Eduardo Reidy and Lúcio Costa sought to democratise access to architectural space through collective housing, leaving a significant legacy in Brazil. However, the 1964 coup constituted a decisive rupture, leading to the persecution of progressive architects such as Vilanova Artigas and Paulo Mendes da Rocha, and weakening the “social function of architecture”1. Influenced by international capital and American imperialism, this period saw the entrenchment of urban segregation, with architecture increasingly becoming a luxury good reserved for the privileged, reinforcing a divided urban landscape of “ghettos of wealth” and “ghettos of poverty”.

Engaging with theoretical contributions from Artigas, Oriol Bohigas and Pedro Arantes, the paper critiques the Architecture of Consumption and its role in reproducing inequality and exclusion, in the context of urban peripheralization in Brazil. It highlights how the loss of access to architectural design in the urban periphery undermines wellbeing and dignity, leading to widespread self-construction in favelas and marginalised areas. These dynamics represent new forms of segregation, with implications that may extend beyond Brazil as democracies weaken and housing policies lose priority.

The paper concludes by advocating a renewed commitment to architecture as a tool for social transformation. It argues for recognising architectural design as a right guaranteed by the State and embedded in territorial development strategies. Alternative approaches, such as those exemplified by Usina de Arquitetura in São Paulo, emphasise co-production, local knowledge, and inclusive processes, promoting social inclusion through architectural design.

From the “Golden Years”: The emergence of a utopia

In the twentieth century, Brazilian architecture experienced a crucial period: from the initial modernist enthusiasm with its emancipatory ideals. Modernist architecture - initially driven by the search for brasilidade and national identity2 - was appropriated and distorted to serve the demands of a political and economic elite.

The arrival of modernist architecture in Brazil in the 1920s coincided with the country’s economic progress, such that in architecture “modernisation emerged as a leap to be taken over the country’s backwardness”3, a challenge embraced by an ambitious aesthetic avant-garde and innovative engineering. Vilanova Artigas, a pioneering figure of modernism, contextualises this emergence:

Brazilian modern architecture has its origins in modernising movements that appeared after the First World War. A period marked by military insurrections, political reform struggles, defined in literature and the arts by the nowfamously Modern Art Week of 19224.

The political discourse of the post-1930 period, under Getúlio Vargas’s government, reinforced the idea of a Brazil “without traditions”, a “tabula rasa” ripe for modernization. However, this process ignored and repressed popular traditions, such as indigenous and quilombola architectures. When elements of these cultures were incorporated, they often constituted appropriation rather than genuine appreciation. The period’s spirit held that “Brazil is a country condemned to modernity”5, imposing a narrative of liberation from traditions, as argued by Mário Pedrosa. While assimilating and reinterpreting foreign influences - like Bauhaus and Le Corbusier - Brazilian modernism nevertheless produced a distinctive style characterized by formal freedom, generous spans, and the artisanal use of concrete.

With the consolidation of modern architecture came iconic experiences such as Flamengo Park, by Afonso Eduardo Reidy and Lota de Macedo Soares, and Brasília, by Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer under President Juscelino Kubitschek (1956-1961). These projects seemed to point towards democratising access to architectural design. In the 1940s, the exhibition Brazil Builds (fig. 1) at MoMA projected Brazilian modern architecture onto the international stage. According to Guilherme Wisnik, this architecture was “universally Brazilian”, reworking foreign influences in a singular manner.

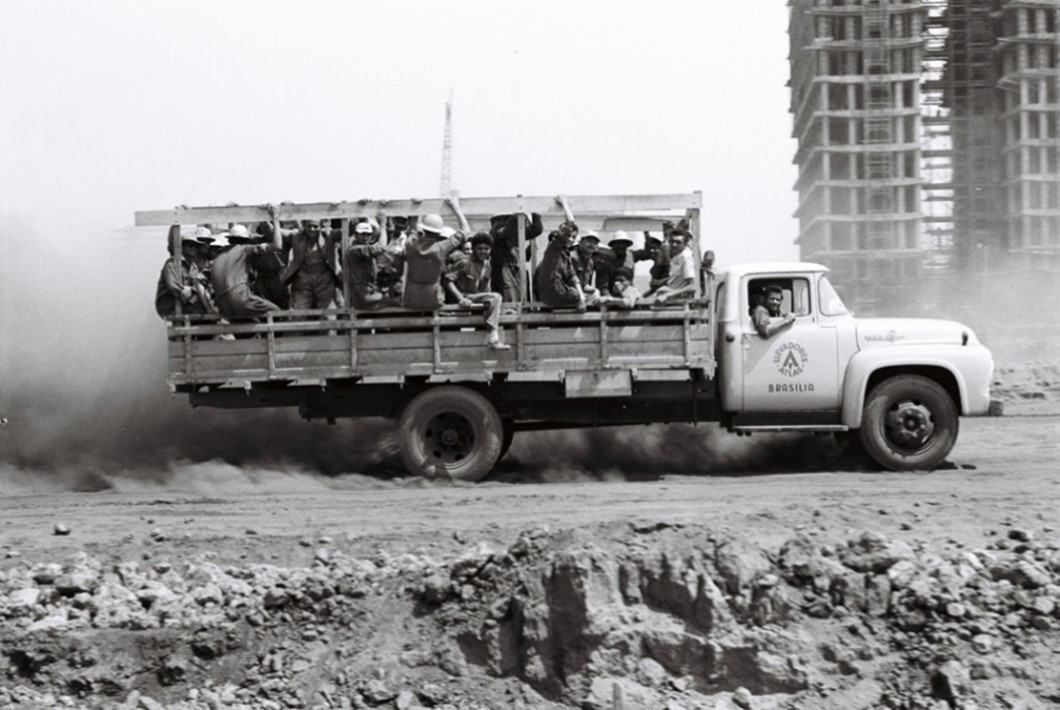

During the “Golden Years” of the 1950s, modern architecture intertwined with other artistic expressions such as Bossa Nova and Concretism, consolidating a modernity paradigm. The Brazil Builds exhibition and the Bossa Nova6 concert at Carnegie Hall in 1962 exemplify this international recognition. Beyond international glamour, this architecture positioned itself to address the realities of a country with deep structural inequalities, challenging those structures so that Brazilian modern architecture would also be architecture of its people, not merely serving a fraction. The construction of Brasília from 1956 onwards, illustrated in (fig. 2), marked the high point of this era, yet its planning also revealed the contradictions and dualities of the modern movement by failing to include workers and migrants in its housing plan - thus generating the first favelas around the new federal capital.

Breaking with the contradictions of a country historically shaped by extractivist, slaveholding and oligarchic legacies was the core challenge for a Brazil striving to assert itself as a modern nation. In the urban realm, these contradictions manifested acutely, driven by the social demands that accompanied profound transformations in the country’s socio-economic structure. With industrialization emerging as the new economic driver, rapid growth attracted large numbers of rural families to urban centers in search of waged employment, sparking an accelerated and unregulated process of urbanization.

Between 1940 and 1980, Brazil’s population grew from 41.2 million to 119 million, nearly tripling, while the proportion of urban dwellers rose from 31% to 67% in the same period (IBGE, 1990). In major cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, this demographic shift exacerbated existing issues of urban peripheralization, informal settlements, and lack of access to dignified housing. In Rio de Janeiro, for example, the proportion of the urban population living in favelas rose from 7.2% in 1950 to 17.6% by 19907.

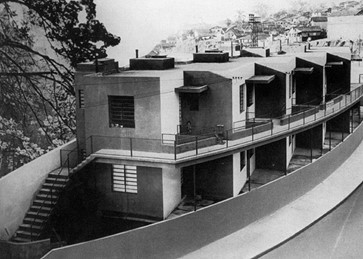

Architectural production during this period included emblematic projects such as the Conjunto Residencial Prefeito Mendes de Moraes, or Pedregulho (1947), by Affonso Eduardo Reidy, and the Copan Building (1951–1966), by Oscar Niemeyer - both promising typological diversity and social mixing. Other lesser-known examples, such as the Vila Operária da Gamboa (1933) (fig. 3), designed by Lúcio Costa and Gregori Warchavchik, and the CECAP Complexo Residêncial (1972), by Artigas, proposed more democratic solutions to the housing problem. Though less celebrated than Niemeyer’s exuberant forms, these projects anticipated post-war concerns about urban life and suggested that architecture could serve as a tool for promoting collective well-being.

We argue that the cycle of euphoria and utopia that defined Brazilian modern architecture reached its decisive decline following the military coup of 1964 - an event that not only interrupted a democratic project, but also severed the architectural commitment to social transformation. From that moment on, architecture was gradually depoliticized, co-opted by market logics, and relegated to serving elite interests. The new regime intensified repression of the favelas and deepened urban peripheralization, instituting a logic of territorial segregation that, as will be discussed in the following section, came to shape the patterns of spatial occupation across Brazilian cities.

The “Dark Years”: The Abduction and Death of Utopia

Following the 1964 military coup, Brazilian modernist architecture lost its role as a State-led project for social transformation. The suppression of progressive and popular movements - directly supported by the United States - ushered in a new urban model shaped by market logic and car-oriented development, reflecting a typically North American influence imposed on cities. Oriol Bohigas, commenting on this global turn, observed that “architecture came to depend on communicational devices beyond its control, such as illuminated signage and symbolic forms.” Urban space became increasingly spectacularised, with architecture shifting from an emancipatory tool to a medium of image and consumption.

US influence in Latin America, particularly in the second half of the twentieth century, materialised in Brazil through cultural, economic, and intelligence support for the military coup. Under the pretext of saving the country from a purported “communist” dictatorship, the US supported the ousting of President João Goulart and offered CIA-led training for repressing democratic opposition. In the aftermath, the regime dismantled democratic structures - suspending elections, outlawing political parties and trade unions—and curtailed the work of architects dedicated to social transformation, such as Vilanova Artigas, Sérgio Ferro, Paulo Mendes da Rocha and Rodrigo Lefèvre.

During the military dictatorship, Brazil experienced significant economic growth (an annual average of 6.3%), driven by an import substitution strategy8. However, this growth coincided with intensified income concentration. Trade union repression and wage suppression expanded corporate elites’ profit margins, while the introduction of monetary correction on public bonds shielded rentiers from inflation. Consequently, the gains from growth were appropriated by the wealthiest strata. As Victor Leonardo de Araujo9 highlights, between 1960 and 1970, the income of the poorest decile grew by 28%, while the richest decile’s income advanced by 67%, increasing their share of national income from 39.6% to 47.8%. Although industrial dynamism generated more skilled jobs, workers’ purchasing power eroded, reducing their relative income, even as the overall mass of income and consumption increased, concentrated primarily among the upper class and the emerging middle class.

Within this context, urban centers expanded to accommodate migrants from rural areas and working-class populations. Despite the military regime’s creation of the Housing Financial System (Sistema Financeiro da Habitação - SFH) in 1964 (Law No. 4,380), aimed at facilitating credit for home ownership, the program was limited to meeting the financing demand of the upper and middle classes. This aspect reinforced social segregation in urban areas. The regime deepened urban peripheralization, instituting a territorial segregation logic that began to guide spatial occupation patterns in Brazilian cities.

During the same period, repression of favelas became a systematic policy aimed at expelling the poorest from urban areas undergoing gentrification. As Paola Berenstein notes, in the context of the dictatorship, “many favelas were systematically demolished and their inhabitants displaced from highly valued land, especially in Rio de Janeiro’s wealthier southern zone"10. In their place, luxury buildings or urban parks were erected, which, rather than democratizing space, served to further enhance the value of these elite areas.

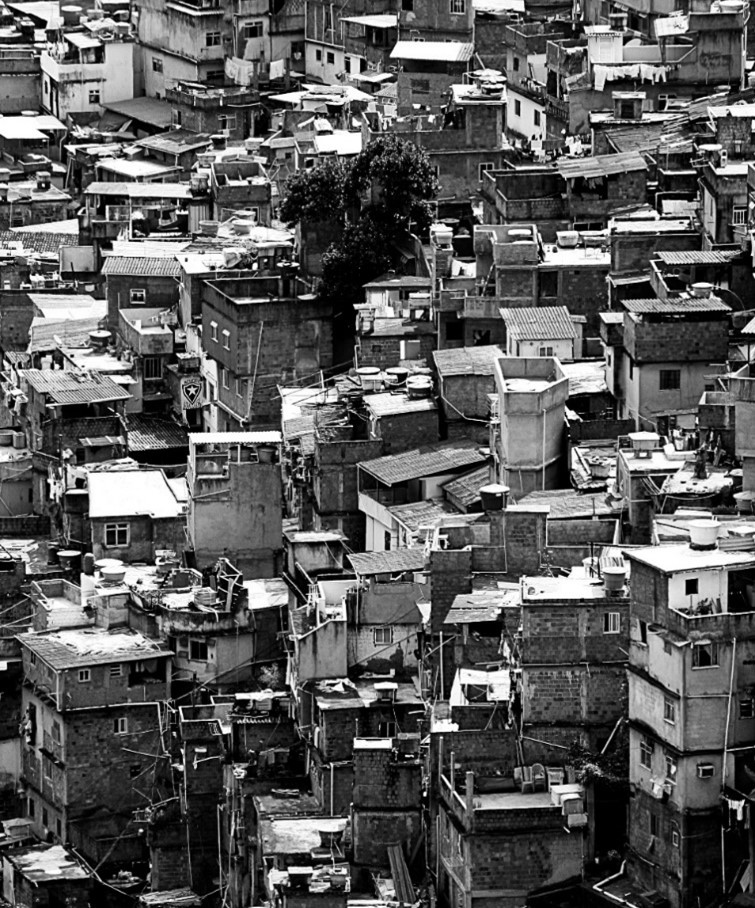

In the consolidation of the so-called “ghettos of the rich,” the State concentrated investments in major road infrastructure projects, expanding residential zones for the elites. An emblematic example is the expansion towards Barra da Tijuca in Rio de Janeiro, where, as it was said at the time, “total socio-spatial segregation was possible”11. There, an urban model combining modernist aesthetics with a deeply exclusionary logic was consolidated. In São Paulo, the launch of the luxury development Alphaville in 1975 reinforces this pattern: built on indigenous lands bordering Carapicuíba - one of the poorest municipalities in the metropolitan area - the project expresses the structural dependency of elites on precarious labor from these territories, a stark residue of the country’s slaveholding culture. Cities thus became the stage for an authoritarian project that instrumentalized architecture and urbanism as tools of planned segregation, pushing poor populations into new favelas or increasingly distant peripheral areas - the “ghettos of the poor.” In contrast, elite “fiefdoms” formed, enclaves protected by infrastructure and private security, imagined as barriers against the chaos and violence of the “real” city. The figure 4 illustrates the Favela da Rocinha.

Caldeira observes that the growth of the middle and upper classes, alongside housing credit, generated intense demand for areas previously inhabited only by workers, raising prices and displacing them to new peripheral zones12. Marginalized at the edges, the poor build their homes through self-construction, often in precarious and illegal conditions. Even with redemocratization opening urban debate, the dictatorship’s legacy - increased social inequality and segregated cities - promoted an unequal urbanization model, deepening fragmentation and weakening architecture’s social function. Brazilian modernism, once an instrument of social emancipation, was emptied and redirected to serve capital’s demands. The 1964 coup imposed a hiatus on this trajectory, crushing progressive agendas and reinforcing the precarization of life.

The attempt to democratize access to architecture and the city, which peaked between the 1930s and 1950s, found its turning point in the military dictatorship, culminating in its failure and the dilemmas persisting today. Consequently, the accelerated expansion of peripheries and favelas reflected a segregatory and unequal State model that neglected displaced populations within Brazil’s territory. Migrants forced by drought, hunger, and underdevelopment sought better living conditions in urban centers but were socially condemned to live in suburbs and favelas where the State is absent and other agents dominate social dynamics.

Concerns regarding contemporary Brazilian architecture arise from the perception of a profound distancing from its former commitment to collective aspirations. Architecture, increasingly confined to an elite, appears to have relinquished its transformative potential as an instrument of social change. Within this scenario, legitimate questions arise regarding the discipline’s role in national development and overcoming historical inequalities. Artigas, in The Social Function of the Architect (1989), already denounced this impasse and claimed the profession’s social commitment: “under the conditions of Brazilian capitalism, as perverse as it is, we architects bear a social responsibility to think utopically in the face of this reality”.

For Artigas, the modern project contained an essential utopian dimension, and the “popular house” symbolised architecture’s greatest twentieth-century ambition—to make dignified housing an accessible right for all, the “Greater Number”13. He recognised that such transformation could only occur through strengthening democratic institutions and the architect’s political engagement. As he stated, “the social exaltation of architecture […] was such that the popular house became the greatest monument of the twentieth century.” In this sense, Brazilian modern architecture, especially between 1930 and 1964, still envisaged a pathway whereby design was a tool of emancipation, capable of collectively addressing urgent social needs.

This understanding was crystallised in events such as the Basic Reforms Rally (Comício das Reformas de Base) of João Goulart’s democratically elected government, held in March 1964 in Rio de Janeiro. The progressive agenda of Goulart’s administration included agrarian and urban reform, which inspired architects and intellectuals of the time with the promise of structuring Brazil as a less unequal nation, with democratised housing access as the ultimate aspiration, truly modern in character.

The deposition of João Goulart and the installation of the military-bourgeois coup in April 196414 shattered the young Brazilian democracy and inaugurated a long period of authoritarianism. With the coup, the utopias of social transformation that mobilized broad sectors of society vanished. Architects, artists, students and political opponents were persecuted, imprisoned, tortured and often killed. Those who could sought exile. The vanguard of progressive Brazilian architecture - often linked to the Communist Party and popular movements - had its professional and academic activities halted. The dictatorship, which lasted until late 1985, dismantled an architectural field committed to social justice.

Between the decades of hope and the brutal rupture imposed by the regime, not only were projects interrupted, but the ideals underpinning them were also eroded. Guidelines for urbanism and social housing were progressively emptied, if not entirely annulled. Architecture, which had sought to respond to collective demands and contribute to building a less unequal country, gradually became a privilege reserved for a few. In this context of repression and curtailment of freedoms, a critical impasse in the history of Brazilian modernist utopia was consolidated: architectural design, which should be part of the right to the city and dignity, transformed into a commodity for a minority, distancing itself from the population and its recognition as a fundamental right, as established in the Federal Constitution (Art. 6).

This reality was linked to the economic context of the time. The military dictatorship’s years deepened inequality and favored the formation of a luxury goods and specialised services market aimed at elites and the emerging middle class. Within this context, architectural design increasingly catered to these classes, capturing a significant portion of professional practice, which adapted to serve this segment. Consequently, social issues - previously central to many architects’ agendas - were relegated to the background.

Since then, access to architectural design in Brazil experienced a rupture – a hiatus in efforts to popularise architecture. This interruption also prevented a critical review of the modern movement and suffocated progressive proposals from its great masters. For example, the São Paulo group comprising Sergio Ferro, Flavio Império and Rodrigo Lefèvre - associated with the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) - sought through the “New Architecture” ideology to revise and expand the design agendas established by Brazilian modernism’s luminaries such as Artigas and Mendes da Rocha.

This group had limited practical impact, resonating more in theory with some contributions to popular participation in architectural debate. Although their discussions were later incorporated into architectural schools nationwide, their influence and positions remained limited at the urban scale. This was largely because their ideas remained a countercultural current within Brazilian universities.

Still, a relevant example is the USINA collective, a group of architects inspired by educator Paulo Freire’s thought, advocating a popular architecture based on mutual aid building efforts - experiences with parallels in Portugal’s SAAL programme. USINA consolidated as a technical advisory group in São Paulo, Usina CTAH, composed of architects and social scientists working with popular movements to produce social housing through self-management (fig. 5). The group collaborates with organizations such as MST (Landless Workers’ Movement). However, despite its relevance, experiences like this remain marginal in contemporary Brazilian architectural practice. We argue that such initiatives need to be expanded nationally, with local training programmes for workers conducted under architects’ technical guidance. This practice has been an acupuncture amidst a country deeply afflicted by social housing challenges.

In Brazil, the right to another societal project never existed, as elites have always co-opted or repressed their opponents. Thus, without restoring voice to the majority, no change is possible. However, for a people oppressed for centuries to express social transformation, it is necessary to invent a pedagogy that still teaches that The Impossible is Possible15.

The Brazilian architecture after modernism, suffocated by democratic suppression, was limited to an uncritical or even fetishized practice of its great masters’ works. The absence of a postmodern movement in Brazil - which in Europe and North America sparked critical debates, either to break with or reinforce modernism’s principles – resulted in a restricted production in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, with few notable exemplars. Brazil lacked figures willing to critically revisit orthodox modernism while acknowledging its tradition, as occurred in Spain and Portugal.

Contemporary evidence suggests that architectural praxis has ceased to meaningfully engage with the lived experiences of ordinary people in a proactive manner. From the “years of lead” under military dictatorship to the subsequent redemocratization processes, urban development has been dominated by American-style urbanism16, featuring enclaves of affluence and poverty. Even social advances during Brazil’s nascent democracy - such as statewide housing programs via Cohabs (Companhias de Habitação), and more recently, the federal Minha Casa Minha Vida I and II - have delivered generic housing typologies applied uniformly from the north to the south of the country. In a country spanning more than five diverse climatic zones, this uniformity constitutes a disregard for contextual responsiveness. Architecture - with a capital ‘A’, as Lina Bo Bardi once advocated17 - when invited to participate, now serves mere bourgeois interests, thus isolating the architectural legacies of those modernist masters from that earlier, more aspirational Brazil.

As a result, unplanned settlements and a pervasive fabric of self-built housing have extended across the territory, marking a process of urban peripheralization. Present from the northernmost inlands to peripheral suburbs across Brazil, these developments typically orbit around economic hubs or city centers. These peripheral areas lack not only architectural design but also urban design. Their predominantly working-class, poor and Black inhabitants are consigned to precarious housing, labor, mobility and leisure conditions. Public authorities exclude these areas from budgetary priorities and large-scale urban projects, which are almost invariably geared towards affluent enclaves and central districts. As Maricato observes, this dynamic is “empirically evident in the formal housing market, which reaches less than 50% of the Brazilian population”18.

Urban peripheralization in Brazil represents a broader phenomenon than favelization alone, though both are often conflated. It refers to urban expansion characterized by precarious housing that, while legally constructed, lacks proper infrastructure, urban continuity and planning. These peripheries emerge not through democratic urban planning, but via speculative and market-driven land occupation: plots sold individually, anticipated for future appreciation, rather than integrated according to territorial or urban quality criteria. Although they differ from favelas - marked by irregular occupation and lack of land titling -these suburbs share their deficit in services, public amenities, and dignified living conditions.

Although slightly better equipped than favelas, these peripheral areas suffer from narrow streets, limited tree cover, deficient public transport and scarce recreational facilities - exposing a model of urbanization that reproduces socio-spatial inequality. Functioning as dormitory suburbs, residents face exhausting commutes and return only at night. Life in the Brazilian periphery entails daily hardship and reveals an architecture stripped of its social role, serving primarily those who can afford it. Both favelas and peripheries reflect the exclusionary dynamics of capital-driven urbanization, in which the State intervenes selectively: investing in central, profitable areas while relegating the working classes to “sacrifice zones”. In a country of continental scale, few architectural practices offer real alternatives for younger generations, as dominant urbanism entrenches segregation and inequality as tools of control.

This phenomenon has manifested year after year, particularly within major metropolitan regions. In São Paulo state, beyond favelas, an extensive peripheral sprawl encompasses cities such as Osasco (fig. 6), Carapicuíba, Guarulhos and the ABC Paulista, forming a continuous urban conglomerate. In Rio de Janeiro, urban segregation is visible not only within principal favelas, but also in peripheral cities like Duque de Caxias, Queimados, Magé and São Gonçalo. Between the 2010 and 2022 censuses, those residing in favelas and informal urban communities increased from 11.4 million to 16.3 million, while such urban fabric expanded from 6.3 thousand to 12.3 thousand agglomerations, according to IBGE data (2024). Maricato highlights:

Brazilian urbanism (understood here as urban planning and regulation) is not committed to concrete reality, but to an order that pertains only to part of the city… The illegal city is unknown in its dimensions and characteristics. It is a place outside of ideas19.

Today, a considerable portion of informal territory exists, and where there is diseño, it comprises buildings utterly disconnected from urban context, climate or geography- often with ground-floor parking and living units beginning on the fourth storey, with no engagement with the street, creating “dead” streets devoid of social life and thus more dangerous. Maricato highlights:

Illegality is, therefore, functional—for archaic political relations, for a restricted speculative real estate market, for arbitrary application of the law, based on patronage20.

This model of peripheralized urban growth, reinforced by selective urbanization policies, continues to shape Brazil’s urban fabric. Informality and precariousness are tolerated and strategically functional, hierarchizing and restricting access to the city. The State intervenes unevenly, prioritizing investment where market value is anticipated while leaving other areas in limbo. In such spaces, the absence of design becomes a political act - a deliberate method of spatial organization that reinforces inequality and exclusion.

We argue this constitutes a project of socio-spatial disorder, condemning the poor to informality that elites exploit.

A large portion of humanity, through disinterest or incapacity, can no longer obey the laws, norms, rules, customs derived from this hegemonic rationality. Hence the proliferation of ‘illegal’, ‘irregular’, ‘informal’ people21.

This invites reflection on architectural practices capable of revealing these exclusionary mechanisms and whether an architecture rooted in territory, cultural context, and social participation can be cultivated beyond the elite sphere.

Brazil’s ongoing political crises are not anomalies, but part of a broader structure that sustains inequality. From the 1964 dictatorship to the 2016 parliamentary coup and the failed coup attempt following Bolsonaro’s 2022 defeat, a pattern of assaults on democracy has reinforced socio-economic and spatial segregation. This reality is etched into the built environment, where architecture becomes commodified, reinforcing exclusion and exacerbating the precariousness of the urban poor.

In light of this, it is crucial to rethink urban intervention strategies. Rather than merely replicating initiatives like Minha Casa Minha Vida or historical experiments such as Arquitetura Nova, a more radical and grounded approach is needed. This entails working from existing realities - as seen in the Favela-Bairro programme - but with deeper, sustained State involvement in marginalised territories. Only through a combination of effective public policy and place-based design strategies can the entrenched segregation of Brazilian cities be addressed.

Urban segregation is not a contingency - it is a pillar of Brazilian society, perpetuated by aristocratic policies inherited from an exclusionary colonial past. Attempts at popular urban reform have often been suppressed, underscoring the necessity for a more confrontational and emancipatory role for architecture and urbanism — proportionate to the systemic forces that perpetuate inequality.

Balanced on a steep and uncomfortable bank

Half-finished and filthy

Yet it is their only home, their possession and shelter

A dreadful stench of sewage in the yard

Above or below, if it rains it will be fatal

A piece of hell, here is where I am

Even the IBGE came here and never returned22.

At this juncture, it is pertinent to introduce an ethnographic perspective: the life experiences of both authors validate theories of segregation and peripheralization. Raised in Osasco’s periphery within migrant families seeking better living conditions - a common trajectory throughout Brazilian urban fringes - this lived experience is not merely biographical, but an epistemic component enriching and challenging the analysis. Experiencing the absence — or oppressive presence — of architecture in these territories cultivates a critical awareness that shapes our professional perspectives.

First-hand awareness of the city’s fringes - its physical, symbolic and social limits - enables us to perceive often-invisible forms of exclusion, as well as modes of resistance, reinvention and space appropriation emerging in these contexts. Acknowledging this trajectory is not an appeal to personal authority, but a position that values epistemologies from the margins, contrasting with the technocratic and abstract detachment that has long shaped architectural production in Brazil. Listening to and considering the voices of those experiencing urban segregation is essential for advancing socio-spatial understanding and ensuring that architectural design acts with these populations - not merely upon them. Bridging the gulf between technical knowledge and real life is an urgent task in light of the prolonged failure of urban policies and historical State neglect.

Worth recalling is that cities often celebrated as planning exemplars - such as Barcelona - also faced acute housing precarity in recent history. The proliferation of shanty towns in mid-20th-century Barcelona exposed the State’s neglect of internal migrant flows and escalating housing demands. In Barcelona entre el Pla Cerdà i el barraquisme23, Bohigas analyses the tensions between the rationalist, egalitarian design of the Eixample and the exclusionary reality of informal peripheries - demonstrating how even paradigm urban modernity cities can succumb to abandoning vulnerable populations.

This parallel suggests that the peripheralization process - defined by State withdrawal in popular territories, replacement of project rights by standardized, decontextualized solutions, and consolidation of a segregationist logic within urban market dynamics - should not be regarded as uniquely Brazilian. Rather, it has the potential to expand globally, especially in contexts marked by democratic weakening, erosion of public housing policies, and the rise of authoritarian regimes.

Brazil’s urban trajectory should be read not merely as a peripheral exception, but as an advanced symptom of an exclusionary urban model that threatens generalization. Far from being solely a denunciation, the Brazilian case operates as a warning: it exposes the dangers of urbanism captured by the market and disconnected from daily life – latter-day conditions replicable worldwide, especially in the Global South. The contemporary challenge demands a critical response that recasts architecture as a tool of territorial justice and confronts the forces intent on transforming cities into privileges - not rights.

This paper has examined how the peripheralization of Brazilian cities- intensified since the 1964 military coup - constitutes not merely an urban phenomenon, but a deliberate political project of socio-spatial segregation. Architecture, once articulated as an instrument of collective emancipation during the modernist cycle, has been progressively emptied of its transformative potential and reified as a commodity accessible only to urban elites. The adoption of North American-inspired urban paradigms, the imposition of standardized housing solutions (as seen in Cohabs and Minha Casa Minha Vida) and the State’s retreat from popular territories have all contributed to the entrenchment of an exclusionary logic of urban land occupation.

Through a critical, situated approach, this article argues that territorial segregation does not stem simply from policy neglect or inefficiency, but from an enduring power structure that spans political crises and regime changes. Events such as the 1964 military coup, the 2016 impeachment, and the 2022 attempted coup reveal a historical continuum in suppressing popular participation and blocking progressive agendas - demonstrating how cities become the material battlegrounds of these conflicts. Within this context, architecture ceases to work with the people and instead acts upon them, reinforcing hierarchies, symbolic frontiers, and social exclusion.

Faced with this reality, it becomes imperative to rethink urban intervention models. It is not enough to replicate ad hoc programs or address technical deficiencies; we must reconceptualize architecture as a political practice committed to territorial justice and the right to the city. This entails recognizing peripheral epistemologies as legitimate knowledge, valuing popular spatial production forms, and ensuring universal access to architectural design as a common good through strong State engagement. Only by bringing architecture closer to the everyday lives of the majorities will it be possible to reverse the historical cycle of exclusion and envisage new modes of inhabitation that do not reproduce rich and poor enclaves shaping Brazilian metropolitan landscapes today.

Paulo H. Soares de Oliveira Jr.

This work was supported by FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. by project reference and DOI identifier . https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.03668.BD

ORCID ID0009-0004-3454-8637

This work is funded by national funds through FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project/support UID/00145 - CEAU.

Eduardo Mantoan

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES).

notes

Artigas, João Batista Vilanova. 1984. “A função social do arquiteto.” In Caminhos da Arquitetura. São Paulo: Edusp.

Bittar, William. 2016. Formação da arquitetura moderna no Brasil (1920–1940). Rio de Janeiro: Docomomo Brasil.

Wisnik, Guilherme, and Fernando Serapião. 2019. Infinito Vão: 90 anos de arquitetura brasileira. São Paulo: Editora Monolito. See: “Artigas e a dialética dos esforços.” In Saltando sobre o atraso: de Niemeyer a Artigas, 31.

Artigas, João Batista Vilanova. 1984. Op. cit., 275 (Our translation).

Pedrosa, Mario. 2015. Arquitetura Ensaios Críticos. Editora: Cosac & Naify ISBN-13: 978-8540507982.

In a public lecture at Escola da Cidade, São Paulo, Guilherme Wisnik stated: “Brazil chose to be born modern,” referring to the acceptance of modern architecture as representative of Brazil as a modern, independent nation. These aspirations were especially manifest in architecture, literature, and the arts, as symbolised by the 1922 Modern Art Week (Semana de Arte Moderna) with figures like Oswald de Andrade, Mário de Andrade, Anitta Malfatti, Tarsila do Amaral, and Manuel Bandeira.

Fesller Vaz, Lilian, and Paola Berenstein Jacques. 2003. “Una pequeña historia de las favelas de Rio de Janeiro.” In Ciudad y Territorio: Estudios Territoriales, Vol. XXXV (136–137): 268.

Tavares, Maria da Conceição. 1972. Da substituição de importações ao capitalismo financeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

Araùjo, Victor Leonardo. 2021. A Macroeconomia do Governo Médico (1969-1974): Uma contribuição ao debate sobre as causas do “milagre“econômico, 304, 2021. Em: Araujo, V.L. & Mattos, F.A.M., A Economia Brasileira de Getúlio a Dilma – novas interpretações. São Paulo: Hucitec.

Fesller Vaz, Lilian, and Paola Berenstein Jacques. 2003. Op. cit., 268.

Ibid. “(...) the combination of popular parceling/self-construction became the metropolitan standard for popular housing, just as peripherisation became the urbanisation model”, 268.

Caldeira, Teresa Pires do Rio. 1996. “Fortified Enclaves: The New Urban Segregation.” Public Culture, Vol. 8, No. 2.

This idea, modern in its matrix, finds a parallel in Georges Candilis’s article “Problèmes d’Aujourd’hui,” written after the 1962 CIAM meeting at Royaumont, where he called for architecture for the “Greater Number”.

The year 1964 is referenced due to the military-bourgeois coup that overthrew Brazil’s democratic state on 31 March 1964. In the years that followed, architects such as Vilanova Artigas and Paulo Mendes da Rocha were banned from practising as professionals and professors. Artigas, for instance, was forbidden to work at the faculty building he himself had designed.

Arantes, Pedro Fiori. 2002. Arquitetura Nova – Sérgio Ferro, Rodrigo Lefèvre, Flávio Império: de Artigas aos mutirões. São Paulo: Editora 34, ISBN 85-7326-251-6: 224. (Our translation).

Rolnik, Raquel. 2015. Guerra dos Lugares. São Paulo: Editora Boitempo.

Bo Bardi, Lina. 2009. Lina por Escrito – Coleção Face Norte. São Paulo: Cosac Naify.

Maricato, Ermínia. 2013. As ideias fora do lugar e o lugar fora das ideias. In Arantes, Otília, Vainer, Carlos, and Ermínia Maricato. 2000. A cidade do pensamento único: desmanchando consensos. Petrópolis: Vozes. ISBN 85-326-2384-0.

Ivi, 122 (Our translation).

Ivi, 123 (Our translation).

Santos, Milton. Por uma outra globalização. 2000. São Paulo: Edusp, 120 (Our translation).

Racionais MC’s. 1993. Song: Homem na Estrada. Album: Raio X do Brasil. [Hip-hop group from São Paulo’s periphery that voiced social inequalities in the 1990s and early 2000s]. (Our translation) See also: https://www.museudasfavelas.org.br/. IBGE means – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics].

Bohigas, Oriol. Once arquitectos. In Venturi, Robert. 1976. Barcelona: La Gaya Ciencia, 1976, 254. ISBN 84-7080-022-1.

Amalya Feldman

Luis Felipe Flores Garzon Angela Person

Tara Bissett

Edited by: Elisa Boeri (Politecnico di Milano), Luca Cardani (Politecnico di Milano) and Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano)