The conclave stands as the foremost irregular papal ritual —alongside coronations and funerals— designed to address the juridical and political discontinuities characterising the sede vacante. In Early Modern times, the conclave entailed the seclusion of the College of Cardinals, who assembled in secrecy (within the Vatican Palace from 1455 until 1775) until a new Pope was elected.

During this period, riots often erupted, leading to the looting of the Lateran Palace and the private residences of the cardinals (Ginzburg 1987, Hunt 2016). Consequently, the Apostolic Palace was safeguarded through a four-tiered protection system, extending from the building’s entrance to the final door before the conclave’s chambers.

Scholarly literature has explored the ceremonial aspects within the broader history of the papacy (Pastor 1886–1933), European diplomatic relations (Poncet 1996, 2002), and from religious (Pirie 1935, Buranelli 2006), ceremonial (Dykmans 1977–1985, Wassilowsky-Wolf 2007, DeSilva 2022), and social perspectives (Paravicini-Visceglia 2018). However, relatively little attention has been devoted to the architectural dimensions —both large and small-scale— that influenced the conduct and outcomes of these elections. The selection of Vatican rooms for the ceremony, the allocation of minimal space and specific objects for each cardinal, and the random assignment of temporary cells where cardinals lived in strict seclusion for unpredictable periods ranging from 10 hours (Julius II, 1503) to 1006 days (Gregory X, 1271), all suggest that the spatial and material aspects of the event played a critical role in shaping the policies for selecting a Pontiff.

This paper examines the spatial measures at both urban and architectural levels by which the College of Cardinals ensured the physical and political protection of the electoral body from the Roman multitude during the sede vacante. It does so by analysing the procedures formulated by the Masters of Ceremonies, and visualised in five key prints produced between 1550 and 1665 depicting the conclave setting within the Vatican Palace.

Despite today’s global media offering almost obsessive coverage of the papal election —laying bare its electoral mechanisms— the actual manoeuvrings that lead to the election of the successor of Peter, and Vicar of Christ on Earth, remain, as in the past, largely unknown. Since at least the 11th century, the transition of the plenitudo potestatis from one Pope to his successor has been guaranteed by the Sacred College of Cardinals. This body convenes in conclave within a designated location and, through an electoral procedure —subject to historical variation— determines who shall ascend the Papal Throne, a choice not necessarily limited to its own members.

However, the College simultaneously constitutes an elite group that threatens the very politico-spiritual existence of the Papacy. Particularly from the early modern period onwards, its oligarchic tendencies have traditionally stood in tension with the monarchical claims of the Pontiff1. This apparent contradiction, rather than signalling a structural flaw, reveals a strategy of self-preservation on the part of the sovereign papal authority —an authority characterised by an inherently immunitary logic. If one considers the appropriation of the concept of immunity from virology —wherein the inoculation of non-lethal quantities of a virus stimulates the production of antibodies capable of pre-emptively neutralising pathogenic effects—2 then the legislative actions undertaken by popes over time to curtail the power of the College may be better understood. These actions, while limiting, nonetheless presuppose the College’s continued existence as essential to sustaining the mystical nature of the pontifical body.

The secret —or rather private— nature of the electoral ceremonial began to acquire a limited public representation from the late 16th century onwards, when the so-called ceremoniali were formalised. These texts detailed the religious and civil ceremonies to be observed during festivals and solemn occasions. One of the most significant examples is the Pontificalis Liber, commissioned by Pope Innocent VIII (pp. 1484–1492) and compiled by the Master of Ceremonies Agostino Patrizi Piccolomini (c. 1435–95), with the assistance of Johann Burchard (c. 1450–1506), and published in 14853. Moreover, Piccolomini also compiled —apparently at the behest of Pope Innocent— the Rituum ecclesiasticorum, which regulated the rubrics to be followed from the conclave, to the papal coronation, the consistory, and during other solemnities of the liturgical year4.

However detailed, these ceremonial texts remained guidelines intended for high-ranking prelates: they defined roles, established ceremonial timings, and ensured ecclesiastical efficacy. What they lacked, however, was a spatial representation of the ceremonies accessible to a broader audience. To address this gap, from the mid-16th century onwards, visual representations of the conclave ceremony began to be produced. By then, the Apostolic Palace had become the established site for resolving the sede vacante. Originally created for commercial purposes, these prints remain the only extant testimony to the architectural role played by the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace in managing the sede vacante and the election of the Pontiff.

This paper adopts an interdisciplinary perspective to reveal how spatial strategies, at both urban and architectural levels, through which the College of Cardinals ensured the physical and political protection of the electoral body from the Roman populace during the sede vacante evolved besides the ceremonial development. It does so by analysing the procedures devised by the Masters of Ceremonies and visualised in five key prints produced between 1550 and 1655, which depict the conclave setting within the Vatican Palace.

The aim is to demonstrate how an architectural analysis —ranging from urban-level measures of social containment to the self-seclusion within the ephemeral micro-architectures of the cardinals’ cells— can contribute to a reappraisal of architectural historiography of the papal election understood as a relational dynamic between the individual cardinal, the Sacred College, and the popolo romano during the sede vacante.

The Papacy is the only absolute monarchy in Europe whose elective form, called the conclave, has survived over time. However, the term conclave did not originally refer to the mechanism or ceremonial election of the Pope. Instead, with con-clavis or cum-clavi, it defined secret, that is, private, material and immaterial spaces, as opposed to an accessible physical environment or a spiritual state of sin.

Festus, in fact, defines the conclave as the rooms locked with a key5. The denied access to these houses' rooms clearly defined their secret quality: “conclave locum secretum dicit in domo”6; while the use of a mechanical device such as keys to lock a room extended the meaning of the conclave to fortified places or remote spaces within a building7.

The spatial metaphor was appropriated by the Christianity of the Church Fathers, who transposed the secret and inaccessible nature of the room to that of the individual soul. Cassian, in fact, warns of the difficulties of investigating “the innermost chambers [conclavibus] of the soul”8, while Ambrose stated that “nothing is hidden from God, nothing is closed [clausum] to the eternal light: but He disdains to open the gates [portas] of malice, He does not wish to penetrate the chambers [conclavia] of wickedness”9.

Nonetheless, the seclusion of the Sacred College of Cardinals was not the initial form of election experience in the Christian tradition. Actually, not even the Pontiff was elected among the cardinals of the College. In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Popes were elected from among the deacons, and specifically, the archdeacon who survived his Pontiff became Pope10.

Subsequently, and until the 9th century, the presbyters elected to the papal throne were more numerous than the archdeacons. It was only in 882 that, despite the ‘prohibition of translation’ which bound the bishop to his diocese, the election of a bishop as Pope gradually became a possibility. It would take until 1185 to see the practice of the two-thirds majority of voters —and not simply acclamation— for the election of a cardinal to the papal throne.

Regarding the nature of the electoral body of the new Pope, the ancient tradition allowed the reigning Pontiff to appoint his successor, and only in the case of unexpected death could the college of clergy replace his will by expressing themselves unanimously or by majority. The political continuity of this custom ceased only in the 7th century when the possibility of appointing the new Pontiff by the reigning one fell into disuse11.

The electoral device thus opened very early —considering the history of the Church— to election rather than appointment. An election that included the ‘popolo’ of the ecclesial community, that is, a restricted social circle that included the clergy and the notables of Rome. Nonetheless, the exclusion of the right to vote for the secular part was decreed in 1059 by Nicholas II (pp. 1059–1061), who established the primacy of the cardinals in the exercise of the vote, thus officially excluding the influences dictated by the Roman nobility.

It was therefore the definition of a socially homogeneous electoral body —the cardinal bishops— limited in number, to which was added the enduring political agency of the local nobility, that laid the foundations for what became a practice, namely the elections in conclave. In 1241, in fact, upon the death of Gregory IX (pp. 1227–1241), the college of cardinals was undecided on the choice to make due to the political crisis that had involved the papacy, the Ghibelline faction, and Emperor Frederick II for years. It was Matteo Rosso of the Orsini family —also destined for a cardinal career— who in that year locked the cardinals in the Septizonium, thus forcing them into coercive seclusion to prompt a decision that was slow in coming12.

The vacancy of the Apostolic See was not only an ecclesiastical and political problem of succession of power but also an economic one. A few years later, in fact, the long vacancy following the death of Clement IV (pp. 1265–1268) in Viterbo risked collapsing the traditionally very advantageous real estate revenues due to the presence of the papal curia in the city. Thus, the local authorities locked the cardinals in the Apostolic Palace on November 16, 1269, even going so far as to uncover the roof in May of the following year to force the cardinals to make a decision. The result was the election of Gregory X (pp. 1271–1276) on September 1, 1271, which ended the longest vacant see in history13.

Remembering his experience as a conclavist ante litteram, Gregory, during the second Council of Lyon convened by him in 1274, proposed the decree for the election of the Pope Ubi periculum, which aimed to protect the Church from the dangers inherent in a prolonged vacant see14. Specifically, Ubi periculum was the first official document that named and defined the necessity of the rigor of the conclave, defined as living “in common in the same hall, without dividing walls or other curtains; this, except for a free passage to a separate room, should be well closed on all sides, so that no one can enter or leave”15.

Furthermore, the seclusion of the cardinals had to be ensured within ten days of the previous Pope’s death. This was accompanied by the rationing of food introduced into the palace through a window and the absolute prohibition of communications to and from the outside.

What dangers did Gregory X aim to address with the issuance of his bull? The political and legal transition inherent in the sede vacante depended primarily on the unique nature of the Pope, understood in his threefold role as Bishop of Rome, sovereign of the Papal States, and Vicar of Christ on Earth. From this latter perspective, and thus from a theological standpoint, since the 14th century, the Augustinian Augustinus Triumphus argued that there could be no discontinuity in the presence of Christ within the Church. As His Vicar on Earth, the Pope’s plenitudo potestatis continues “in the College or in the Church, which is simply that of Christ himself, the incorruptible and everlasting head”16. As Luigi Spinelli recalls, Triumphus, following Henry of Segusio, supported the principle that the transfer of papal potestas from the deceased Pope to the elected one was transmitted by the mystical body of the College of Cardinals, who were as close to the Apostles as the Pope was to Christ17.

The theological argument aimed at stabilising the principle and process of juridical-political continuity between Popes. However, it risked, in the writings of medieval theologians and glossators, attributing excessive power to the College, so much so that Triumphus himself wondered:

Whether the College can do anything without the Pope that it can do with the Pope, or whether the College can do anything when the Pope is dead that it can do when the Pope is alive... is perhaps doubtful18.

This was perhaps the internal danger, a sort of risk of autoimmune disease, that Gregory X aimed to prevent when, in the Ubi periculum, he urged the Cardinals to make a quick decision in the conclave, decreeing that

During the time of the election, the aforementioned cardinals shall receive nothing from the Apostolic Chamber, nor from anything that may come to the same church from any source during the vacancy; instead, all revenues during this time shall remain in the custody of the one [the Camerlengo] to whose fidelity and diligence the Chamber itself has been entrusted, to be at the disposal of the future Pope19.

But the danger to be avoided did not only come from within. If, indeed, the power of the Pope was guaranteed continuity through his mystical body of cardinals —even if through a theological device— the same did not apply to the earthly auctoritas attached to the physical body of the Pope as Bishop of Rome. As Reinhard Elze has demonstrated through a series of examples that testify to the existence of a tradition rather than a rule, the Pope’s corpse and effigy were not immune to the possibility of being disrupted, both symbolically and materially. Thus, Jacques de Vitry, arriving in Perugia in 1216,

found Pope Innocent [III] dead, but not yet buried. During the night, some people stealthily stripped him of the precious garments with which he was to be buried; they left his almost naked and fetid body in the church20.

The same fate awaited the earthly remains of Innocent IV (pp. 1243–1254), as well as those of Clement V (pp. 1305–1314).

But the assault on the ‘body of the Pope’ was not limited to the corpse but also extended to his memory. It happened repeatedly during the 16th and 17th centuries that statues erected in Rome to commemorate Paul IV (pp. 1555–1559) in 1559 and Urban VIII (pp. 1623–1644) in 1640 were subjected to mob violence, while that of Sixtus V (pp. 1585–1590) narrowly escaped destruction21.

Finally, not only were the immaterial assets (economic revenues of the Pope) and his physical body and effigy at risk, but also the material goods and physical spaces that defined the nature of his office. This includes the stripping of the precious liturgical vestments that covered the corpse of Gregory the Great (pp. 590–604) in 595, as well as the disappearance of all sacred objects that adorned the corpse of Sixtus IV (pp. 1471–1484) in 1484. As Johann Burchard recounts,

After [Sixtus] death, all the most reverend cardinals present in the city came to the palace and passed through the room where the deceased lay on the bed, dressed in a long robe over a shirt, with a cross on his chest and his hands folded […]. The Abbot of Saint Sebastian, the sacristan, had a bed with furnishings, although it should rather have belonged to our office. All other items, as soon as the deceased was carried out of the room, were taken away in a single moment, so to speak; for from the sixth hour until that hour, despite all my diligence, I could not obtain a single basin, a single sheet, or any vessel in which wine and water with fragrant herbs could be prepared for washing the deceased, nor clean trousers and a shirt for dressing the deceased…22.

The traditional looting of goods, along with the intrusion and plundering of the palace of the cardinal elected as Pope, is evidenced by a series of decrees that were periodically issued, and evidently constantly violated. An example is the Decretum de non spoliando eligendum in Papam issued during the Council of Constance in November 1417:

Therefore, we have sometimes found that when a Roman Pontiff is elected, some, under the pretext of a certain pretended abusive license, falsely claim that the goods and possessions of the elected, as if they had obtained the summit of wealth, are granted to the occupier. They not only invade, seize, occupy, and transport the houses, goods, and possessions of the elected, but sometimes also those of some whom they falsely pretend to be elected, as well as the goods of the cardinals and others present in the conclave, considering them as profit. If this were allowed, many dangers, scandals, plundering, thefts, and sometimes murders and homicides would follow23.

In the 17th century, the deceased Pope’s body assumed a fundamental role in the conclave reform promoted by Gregory XV (pp. 1621–1623) in 1621 and 1622. Despite the key points of the Constitutions Aeterni Patris filius (December 15)24 and Decet Romanum Pontificem (March 12)25 aimed at favouring the elective method by secret ballot over the methods of election by acclamation and adoration, a preparatory document shows the intention —disregarded by the Constitutions— to incorporate the Pope’s corpse within the conclave and display it in the Sistine Chapel as a reminder of the transience of worldly life26.

This immunitary attitude of incorporating the element that had until then become the focal point of symbolic disruption and material looting by the populace and the curia itself is not surprising. With Gregory XV’s Constitutions, the ceremonial of the conclave election assumed the rigidity of a strictly regulated rite in all its parts27.

As a result, in addition to the spiritual defence against worldly temptations practiced internally, a procedure was established for measures against possible riots and attacks from the outside. This defence was already outlined in the Pontificalis Liber drafted under the pontificate of Innocent VIII (pp. 1484–1492) by the Master of Ceremonies Agostino Patrizi Piccolomini with the help of Johann Burchard in 1485. In the first book of the Pontifical, Piccolomini recognises a ‘double-quadruple’ system of protection. The outermost was constituted by three hundred infantrymen led by a high-ranking prelate or a powerful noble who guarded the first gate day and night28. The second concerned the first access gate to the area under conclave, and it was the responsibility of lay members appointed for security, such as the conservators and noble citizens29. The third protection concerned the gate from the Apostolic Chamber to the conclave and was the responsibility of foreign dignitaries appointed by the Master of Ceremonies30. The fourth protection was the gate to the conclave, whose guard was entrusted from the outside to six or eight “most dignified prelates of the Roman curia [...] chosen from different nations” to signify a common commitment to safeguarding the event’s sacredness31. Finally, reflecting the first four external defensive circles, four internal and four external locks closed the porticulum, the final gate to the conclave32, whose keys were assigned to the clerics of ceremonies from the inside, and three to the external prelate guards33. The conclave is thus a political phenomenon that spatially reconfigures the Vatican palace, both in relation to the outside urban landscape and internally.

The period of sede vacante and the conclave were events in which the entire city of Rome was involved from the perspective of public order reorganisation, with the Apostolic Palace as the epicentre of interest34. The confusion and simultaneous expectation brought about by the event was due to the unpredictability and secrecy of the electoral process. The variability in the times with which Popes were elected in the Early Modern period can be attributed to various political causes, both external and internal to the curia. Among the former, the shifting power balances between foreign states and their ability to influence choices through diplomatic agency and the persuasion of cardinals played a significant role35. Internally, the role of family and power factions within the College, combined with the electoral system most commonly adopted, such as acclamation or access, had a decisive impact36.

Despite the study of these political circumstances and agencies benefiting the understanding of a single election, the human and unknown quality of these factors becomes irrelevant if we aim to offer an overview and comparison of several conclaves over the long run. This, in turn, may be considered insignificant for the outcome of a single election but important for highlighting the significance —such as in the use of physical space— of a small detail that was previously considered a constant.

A foundational element for the continuity of the sovereignty of the Holy See and the unique agent in the electoral moment of the conclave is the Cardinal elector. Beyond their creation, affiliation, and voting preference37 —which, at least in cases of election by secret ballot, will always remain unknown— their number is a quantifiable parameter. The trend during the period in which conclaves were held in the Vatican from the 15th to the late 17th century shows a constant increase, with a decline only in the following century (fig. 1). This indicates an increasing political weight of the College in relation to the office to be elected. Not coincidentally, a long-run analysis shows how the average age of cardinals elected as Pope progressively rises over the three centuries considered, while the average duration of pontificates progressively decreases (fig. 2). This indicates that a strong College corresponds to a weaker papal office with potentially less room for manoeuvre.

Equally significant is the apparent correlation between the growth in the number of electors within the College of Cardinals and the disproportionate increase in the duration of the conclave, both in progressive average terms and when measured in century intervals (fig. 3). If the average duration of the event in the 15th century was about five days, it increased to eleven days in the 16th century, reached 51 days in the 17th century, and averaged 94 days in the following century.

The cardinals were not indifferent to this increase in seclusion time, and there were signs indicating moments of crisis in this forced cohabitation. Despite progressively improving hygienic conditions over the centuries, the lack of air due to the almost complete sealing of all doors and windows, for example, made the death of College members not entirely sporadic38.

As Marc Dykmans shows in a reconstruction based on the drawing of Uffizi 3989 A (fig. 4)39, in preparation for the conclave, a temporary wall was built dividing the Sala Regia, located on the first floor of the Vatican Palace, into two unequal zones. The northern zone of the Sala was part of the conclave’s cloister, while the southern zone was accessed via the Scala del Maresciallo, originating from the eponymous courtyard under the control of the Savelli family40. The passage point in the wall was the porticulum, the only access and exit door, and the defensive bulwark of the conclave. All windows facing external spaces were sealed. The premise of the ceremony was the prohibition of anyone entering or exiting41, as well as communication between the inside and outside42. This absolute prohibition had one exception: a narrow window through which food could be introduced without allowing the passage of a human body43.

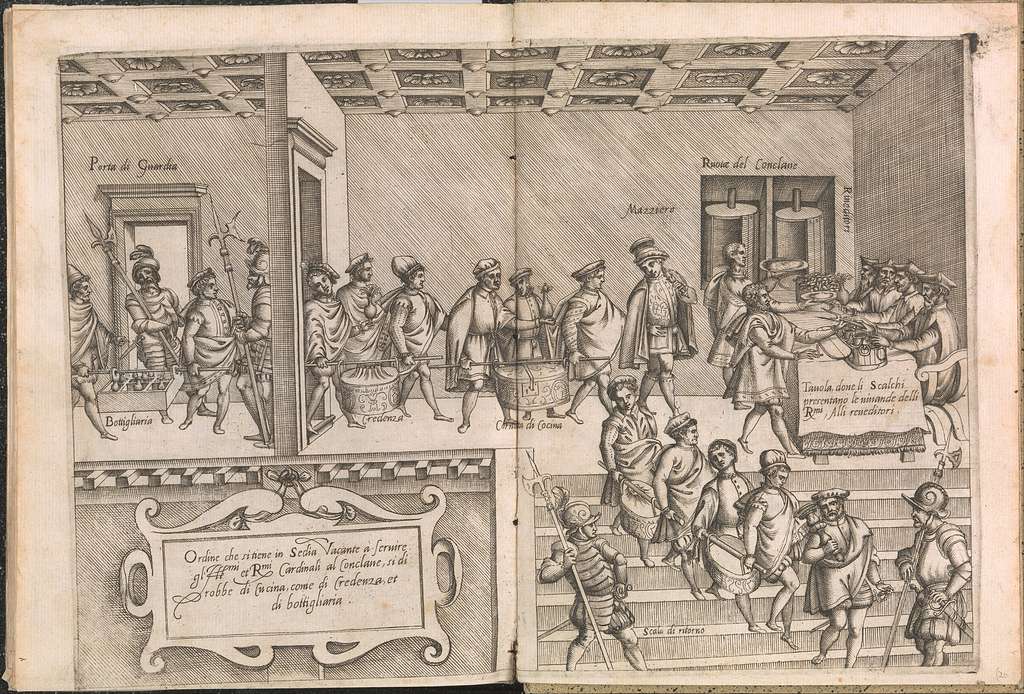

Food was thus the only regularly introduced vector —often rationed to induce the Cardinals to make a quick decision— through the physical borders of the cloistered area. The food prepared elsewhere, contained within the cornuta, was transported by the dapiferi to the foot of the Scala del Maresciallo and finally introduced by the grooms through the ruote44, a rotating device that allowed the safe passage of objects through the porticulum (fig. 5)45.

As previously mentioned, the anticipation for the outcomes of the conclave among those residing in or arriving in Rome was significant. Equally significant was their curiosity regarding the preparations for the ceremony. Various accounts indicate that crowds of people gathered in the Sala Regia and the surrounding areas to observe the form and scale of the event46. Its arrangement and internal organisation, the spaces designated for the conclave at that specific moment, the layout and construction of the Cardinals’ cells, and the assignment of their names to these cubicula, thus became a public event preceding the “extra omnes!”, the moment when the doors were closed. In this sense, the papal curia offered the public a first glimpse of what would soon be closed off to everyone. This glimpse, however, would be captured in a series of drawings that, from a certain point in history and throughout the early modern era, would accompany citizens and pilgrims as they awaited the electoral result, while also stimulating considerable commercial interest.

To date, 45 conclave drawings have been published. Most of these were rediscovered by Cardinal Franz Ehrle47. According to Ehrle, the oldest Conclavepläne belongs to the collection of the Vatican Apostolic Library, while other drawings from later periods were passed down and even printed abroad, in France and Germany, either following or combining parts of models created in Rome. However, beyond a genealogical reconstruction —which Ehrle himself, along with Hermann Egger, sketches out— that would require the publication of the remaining 65 known examples (up to the end of the 18th century), what is of interest here is identifying how some of these conclave plans can serve to describe a shift in the use of space within the Vatican Palace during the electoral event and the perception that was intended to be communicated through the medium of print.

1) Valerium et Lodovicum Fratres Brixienses, 1550

Among the oldest known graphic representations of a conclave is a woodcut measuring 442 x 318 mm, printed by Valerium et Lodovicum Fratres Brixienses (fig. 6)48. The drawing refers to the conclave convened for the death of Paul III Farnese (pp. 1534–1549) on November 10, 1549. In the upper right corner, a chronology of events informs about the main facts observable from an external perspective: the gradual arrival of the Cardinals; the funeral of the deceased on November 28; the Mass of the Holy Spirit and the beginning of the cloister the following day. Once the conclave began, other Cardinals entered the Papal Palace, while on December 19, the eighty-three-year-old Cardinal Filonardi (“Verulanus”) was taken out of the palace to Castel Sant’Angelo, where he died the same day. Other Cardinals left, probably exhausted or ill. Ridolfi and Cybo left the cloister on December 20 and 23, respectively; both returned, but Ridolfi died there on January 31.

The almost frenetic succession of dramatic events for the cardinals was the consequence of a conclave that was about to become the longest in the last two centuries. This —along with the entry into the Jubilee Year of 1550— was probably the reason that induced the Fratres Brixienses to publish a visualisation of the event on February 3, 65 days after the start of the ceremony, a period that had already exceeded by two weeks the recent conclave for the death of Adrian VI (pp. 1522–1523) which lasted 49 days.

In addition to the account of events, which aimed to present the print as an updated document and thus commercially appealing to pilgrims, the drawing showed the cells whose arrangement, for the first time since conclaves were held in the Vatican, exceeded the Sistine Chapel. The reason for this choice was the increased number of Cardinal electors, which rose from 35 to 51.

The cells, distributed by lot to the electors, consisted of a structure measuring

twenty palms in length [4.5 m], while the width and height are fifteen palms [3.3 m], made of square wood, with the floor covered by planks, while the walls and ceiling are covered by a cloth, commonly called ‘saia,’ green in color if the cardinals are elderly, while if they were created by the deceased Pope, the color is purple49.

As the drawing shows, nineteen cells were built in the Sistine Chapel, seven in the Sala Regia, sixteen in the first and second Sala Ducale (Sala Concistorii Publici), five in the antechamber, and four in the Sala del Concistoro Segreto. The architecture of the Palace is treated schematically: the mass of the walls is beyond the scope of the representation, and the proportion of the rooms is referenced only by the number of cells contained therein. However, through concise labels, the memory of the visitor is oriented, allowing them to easily recall the experience of their direct visit while awaiting the election of Julius III Del Monte (pp. 1550–1555) as Pope.

2) Natale Bonifacio, 1585

The second plan here considered refers to the brief conclave held for the death of Gregory XIII (pp. 1572–1585), which lasted from April 21 to 24, 1585 (fig. 7)50. Of the plans published so far, this was the first in a landscape format, measuring 224 x 343 mm. The engraving was prepared before the start (“elezione da cominciarsi alli 22 Aprile”) but was published only after the conclave’s conclusion, given the coat of arms of Pope Sixtus V placed at the centre of the Cortile del Pappagallo. The author was Natale Bonifacio, an experienced engraver and printer from Capua who had already produced a considerable number of engravings thanks to his relationships in Rome with major printers of the time, such as Antonio Lafréry and Claude Duchet. In this print, Bonifacio’s commercial intelligence is evident from the use of the vernacular language, more accessible to the readership of pilgrims to whom it was addressed, compared to Latin, the language of the clergy. The “Vera Pianta del Conclave” thus includes a series of environmental details, such as the indication of the position of the torches “accese per l’oscuranza del Pas[s]agio,” and distinguishes the cells covered with green fabric (V) “usato dali Cardinali antiani” from those in “pavonazo […] usato dali Cardinali Nuovi.” The depiction of the Vatican Palace’s architecture, unlike the Fratres Brixienses’ plan, is realistic in the rendering of wall thicknesses and the position of elements such as doors, windows, and stairs. At the top of the Scala del Maresciallo, the “ruote che servono al conclave” for accessing food to be consumed in the “loggia di Pasteggio” (T) on the Belvedere corridor are indicated. The boundaries with the outside, and thus the conditions of the cloister, are emphasised by the air vents (Y) surrounded by “cancelli per resistere alla turba” (BB). Given the impassability of the Scala del Maresciallo door, Cardinals needing to re-enter the conclave would be admitted through a different door (CC) near the Pauline Chapel (A).

Despite the numerous references listed in the legend at the top left, the building plan is far from being the result of a survey. As Ehrle notes, despite the majority of Vatican rooms being irregular in shape, Bonifacio prefers to render them all with orthogonal walls. Additionally, this is the first plan oriented with north at the top, a choice that facilitates the representation of the area affected by the conclave, which increasingly moves away from the Sistine Chapel. Here, only eight cells were arranged, none were installed in the Sala Regia, while all the others were placed in the rooms around the Cortile del Pappagallo, occupying all the rooms of the Borgia Apartment. The final innovative detail is the precision with which the cells were represented, equipped with doors that, in most cases, never faced those of the opposite cell. To the right of the drawing, a legend lists the Cardinal electors, corresponding to the number assigned to them and their respective rooms. Cardinal Felice Peretti (“M. Alto,” from the name of his father Peretto di Montalto), the future Pope Sixtus V, occupied cell 50 in the second Borgia Hall.

3-4) Nicolas Van Aelst and Giovanni Maggi, 1605

In 1605, the representations of the conclave underwent an evolution that proved crucial for all future plans engraved in the following centuries. The novelty, introduced already in the conclave for the death of Clement VIII (pp. 1592–1605), was to combine the architectural drawing with scenes depicting the course of the ceremony, from the death of the Pope to the election of the new Pontiff. However, it was with the subsequent conclave, convened after the death of Leo XI (pp. 1–27 April 1605) in the same year, that these scenes achieved a balance that made them an integral part of the conclave plans in future centuries.

The attention aroused by the previous conclave, which concluded in April 1605 must have attracted the attention of engravers and publishers when, after only 25 days from his election, Leo XI died. It was then that two prominent figures of the time, Nicolas Van Aelst and Giovanni Maggi, produced two important engravings to compete in the market.

The one signed “Nicolo Van Aelst formis”51 is a woodcut measuring 260 x 383 mm and is the more cohesive representation of the two (fig. 8). Desptite the schematic nature of the palace plan, for the first time, this becomes an element of a broader narrative that starts from the Pope’s death and describes how and who acted outside and inside the fortifications built for the security of the cloister. Thus, the Swiss guards (playing dice), the district chief quelling a crowd attack, the dapiferi transporting the cornuta and delivering it to the grooms, the wheel assistants, and a long prayer procession for the election of the new Pontiff are depicted.

The etching by Giovanni Maggi, on the other hand, adopts a different communicative strategy (fig. 9)52.The print is almost twice as large (410 x 543 mm), and the center line clearly divides the contents, suggesting the possibility of folding the sheet in two. The left part is introduced by two small scenes: the crowd in anguish at the bedside of the dead Pope, and Saint Peter receiving the keys to Paradise, while at the bottom, a prayer procession crosses Ponte Sant’Angelo towards the Vatican. The conclave plan is placed at the centre. The drawing breaks with the orthogonal schematism of previous plans, although the wall masses are still too simplified to derive from a survey. For the first time, the Sistine Chapel is free of cells, which are instead arranged in the rooms around the Cortile del Pappagallo and beyond the Belvedere Corridor (67 cells are indicated).

However, it is the right part that deviates most from tradition: a long text at the bottom refers to a sequence of seven drawings at the top. For the first time, the physical construction of the conclave is depicted, from the creation of the wooden structure, the covering with boards and cloth, the interior furnishings, to the creation of “di un poco di stradella per comodità di passare,” thus demonstrating the cramped arrangement of the cells. The fifth drawing shows the set of objects each Cardinal is allowed to bring: a devotional painting, a kneeler, a bed, a chair, a bell, a small table, a chest, a small cupboard, a pulpit, an inkwell, a stool with a bench, a large lantern, a high stool, a small ladder, a broom and trash basket, a candlestick, a strongbox, three bowls, and a silver jug, a bellows. Finally, always accompanied by textual description, the food and those who transport it are depicted, ending with the ballot counting in the Pauline Chapel, which will assign the Apostolic office to Paul V Borghese (pp. 1605-1621).

5) Giovanni Giacomo de’ Rossi, 1655

In 1655, coinciding with the death of Innocent X Pamphilj (pp. 1644–1655), Giovanni Giacomo de’ Rossi, the most active printer of the de’ Rossi dynasty, whose activity began in Rome under the guidance of his father Giuseppe, entered the conclave print market. His activity is recorded through prints produced between 1638 (the year of his father’s death) and 1691, when his death passed the business on Via della Pace to his son Domenico53. The first printing by de’ Rossi is a watershed for the genre in question (fig. 10)54. The plate contains all the main elements that will characterise the adaptations proposed by the publisher —and his successors— for subsequent conclaves, as well as influencing the equally successful works of Giovanni Battista Contini and Giovanni Battista Falda. This first example, whose engraver is unknown, seems to give relative importance to the list of Cardinals, relegated as it is to the lower left part of the frame. In this detail, Giovanni Giacomo’s commercial experience immediately emerges, dedicating a well-defined frame to this and other elements whose areas on the copper plate will be adjusted to update the contents. The most striking characteristic —and perhaps the success of this model— is the modulation between architectural drawing and the scenes contained in the frames. The plan of the Vatican Palace fits recognisably into the frame through the north-south positioning of the Loggia delle Benedizioni at the bottom, dividing the sheet in two. The plan demonstrates knowledge of the Vatican Palace and is updated with Bernini’s Scala Regia drawn in dashed lines, and Martino Ferrabosco’s Clock Tower in St. Peter’s Square (whose demolition and replacement with Bernini’s corridor is recorded in de’ Rossi’s plate adaptation for the 1667 conclave). Additionally, the tower, part of Sixtus V’s Palace, and the interior of the Cortile del Pappagallo are drawn in ichnographic projection to emphasise the separation of the outside world from the cloistered area. Surrounding the plan, fourteen liturgical and secular scenes complete the artboard. Counterclockwise, the Pope’s funeral, the Mass of the Holy Spirit, the kissing of the deceased’s foot, the entrance to the conclave, the votive procession on Ponte Sant’Angelo, the thousand soldiers of Marshal Salviati, the “Capo Rione” night patrol through the city, the transport of food to the ruote, up to the Cardinals’ cell, the adoration of the elected Pope, and his conduct to the Basilica for the Coronation. De’ Rossi’s composition was produced with future use in mind, making it one of the most successful models of the 17th century, and inaugurating the mature Baroque under the auspices of the elected Pope Alexander VII Chigi (pp. 1655–1667).

The conclave stands as the foremost irregular papal ritual —alongside coronations and funerals— designed to address the juridical and political discontinuities characterising the sede vacante. In early modern times, the conclave entailed the seclusion of the College of Cardinals, who assembled in secrecy (within the Vatican Palace from 1455 until 1775) until a new Pope was elected. During this period, riots often erupted, leading to the looting of the Lateran Palace and the private residences of the Cardinals. Consequently, the Apostolic Palace was safeguarded through a four-tiered protection system, extending from the building’s entrance to the final door before the conclave’s cells.

In this political contest, the spatial organisational arrangement of the event played the reciprocal role of cause and effect. This is why the representations of the conclave plans, whose creation likely began in 1550, are crucial for understanding the mechanisms and the role that architecture played in the relationship with the outside and within the electoral event itself.

Although these plans were drawn for commercial purposes, their conception tells, on the one hand, the role of the College of Cardinals in the political dispute for the predominance of a candidate, but also the difficulties experienced by individual prelates in the constraints of a cloister whose duration was inscrutable and often led to death.

On the other hand, the commercial success of these prints narrates the anxiety that the power vacuum inherent in the elective office of the Papacy created among believers, as well as in the courts throughout Europe, and the need to establish security systems against urban disorders. But they also convey the anticipation for the election of a single person, that unique figure who “lives by dying and dies by living”55.

This work was supported by the Carlsberg Foundation under Grant CF23-1239.

notes

Prodi, Paolo. 1982. Il sovrano pontefice. Un corpo e due anime: la monarchia papale nella prima età moderna. Saggi 228. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Esposito, Roberto. 2002. Immunitas. Protezione e negazione della vita. Torino: Einaudi. §1.

Żak, Łukasz. 2023. “Vademecum delle fonti scritte nell’ambito dell’Ufficio delle cerimonie pontificie a cavallo tra il XV e il XVI sec.” Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 32: 375–398.

Marcello, Cristoforo, and Agostino Piccolomini Patrizi. 1516. Rituum ecclesiasticorum sive sacrarum cerimoniarum S.S. Romanae ecclesiae. Libri tres. Venetiis.

“Conclavia dicuntur loca, quae una clave clauduntur.” Festus, Sextus Pompeius. 1839. De verborum significatione quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome. Lipsiae: Libraria Weidmanniana, 38.

Internationale Thesaurus-Kommission. 1991. “conclave.” In Thesaurus Linguae Latinae. Editus iussu et auctoritate consilii ab academiis societatibusque diversarum nationum electi, IV:71–73. Lipsiae: B. G. Teubner.

“interius cubiculum, sed proprie domus sic appellatur; locus clusus vel munitus vel domus quae multis concluditur cellis.” Ibid.

“de intimis animae conclavibus.” Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. 1846. Patrologiae cursus completus. Joannis Cassiani Opera Omnia. Vol. 49. Paris: Garnier Fratres, 803.

“nihil deo est obseratum, nil clausum aeterno lumini: sed portas malitiae dedignatur aperire, conclavia non vult penetrare nequitiae”. Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. 1844. Patrologiae cursus completus. S. Ambrosii tomi primi. Vol. 15. Paris: Garnier Fratres, 1432.

Paravicini Bagliani, Agostino, and Maria Antonietta Visceglia. 2018. Il Conclave. Continuità e mutamenti dal Medioevo a oggi. Roma: Viella, 15.

Ivi, 18.

Hampe, Karl. 1913. Ein ungedruckter Bericht über das Konklave von 1241 im römischen Septizonium. Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung.

Ceccaroni, Agostino. 1901. Il Conclave: storia, costituzioni, cerimonie. Torino: Giacinto Marietti.

Gregorius X. 1274. “Ubi periculum,” July 7.

“In eodem autem palatio unum conclave, nullo intermedio pariete seu alio velamine, omnes habitent in communi, quod servato libero ad secretam cameram aditu, ita claudatur undique, ut nullus illud intrare valeat vel exire.” Ivi, §1.

“In Collegio vel in Ecclesia, quae est simpliciter ipsius Christi capitis incorruptibilis et permanentis.” Quoted from Spinelli, Luigi. 1955. La vacanza della Sede Apostolica dalle origini al Concilio Tridentino. MIlano: Giuffrè,164.

Ibid.

“an possit Collegium sine Papa, quidquid potest cum Papa, vel an possit Collegium mortum Papa, quidquid potest Papa vivens ... forte est dubium.” Ivi, 167.

“Quibus provisione non facta decursis, extunc tantummodo panis, vinum et aqua ministrentur eisdem, donec eadem provisio subsequatur. Provisionis quoque huiusmodi pendente negotio, dicti cardinales nihil de camera papae recipiant nec de aliis eidem ecclesiae tempore vacationis obvenientibus undecunque, sed ea omnia, ipsa vacatione durante, sub eius cuius fidei et diligentiae camera eadem est commissa, custodia maneant, per eum dispositioni futuri pontificis reservanda.” Gregorius X. 1274. Op. cit., §1.

“Post hoc veni in civitatem quandam que Perusium nuncupatur, in qua papam Innocentium inveni mortuum, sed nundum sepultum, quem de nocte quidam furtive vestimentis preciosis, cum quibus sci erat, spoliaverunt; corpus autem eius fere nudum et fetidum in ecclesia relinquerunt.” De Vitry, Jacques. 1960. Lettres De Jacques De Vitry. Edited by R.B.C. Huygens. Leiden: Brill, 73. Mentioned in Elze, Reinhard. 1977. “‘Sic transit gloria mundi’: la morte del papa nel medioevo.” Annali dell’Istituto storico italo-germanico in Trento = Jahrbuch des italienisch-deutschen historischen Instituts in Trient 3: 23–41.

Delbeke, Maarten. 2012. The Art of Religion: Sforza Pallavicino and Art Theory in Bernini’s Rome. London: Routledge, 101-102.

“Quo defuncto, venerunt ad palatium reverendissimi domini cardinales omnes in Urbenpresentes et per cameram, in qua defunctus jacebat supra lectum, veste quadam longa suprancamisiam indutus, supra pectus crucem habens manibus compositis, defuncto reverentiam profundam facicbant cardinalarem; […] Abbas Sancti Sebastiani, sacrista, habuit lectum cum fornimentis, licet ad officium nostrum potius pertineret. Alia omnia, quamprimum defunctus ex camera portatus est, unico momento, ut ita dicam, sublata sunt; nam ab bora VI usque ad illam horam, omni diligentia per me facta, non potui habere unum basilem, unum linteum vel aliquod vas, in quo vinum et aqua cum herbis odoriferis prò lavando defuncto ordinaretur, neque bracas et camisiam mundam prò defuncto induendo, …” Burchard, Johann. 1911. Liber notarum ab anno MCCCCLXXXIII usque ad annum MDVI. Edited by Celani, Enrico. Vol. 1. Rerum Italicarum scriptores. Città di Castello: Lapi, 14–15.

“Cum itaque nonnunquam evenisse comperimus, quod electo Romano Pontefice, nonnulli sub prætextu prætensæ cujusdam abusivæ licentiæ, res & bona sic electi, quasi culme divitiarū adepti, falsò prætendentes occupanti concedi, nedum illius sic electi, imò aliquando nonnullorum, quos electos esse mendaciter confingunt, domos, res, & bona illorum, nec non bona aliquando Cardinalium, & electorum Romani Pontificis & aliorum in loco conclavis existentium, etiam violenter invandunt, rapiunt, occupant, transportant, lucrifacta existimantes: Ex quibus, si permitterentur, plura pericula, scandala, rapinæ, furta, & nonnunquam cædes & homincidia sequerentur: Nos igitur tam scelerate temeritatis & audaciæ viam precludere, & hujusmodi periculis & scandalis obviare volentes, præfactum damnantes sceleratum abusum, talia fieri hôc edicto perpetuo prohibemus.” Hardt, Hermann von der, ed. 1699. “Decretum de non spoliando eligendum in Papam.” In Magnum Oecumenicum Constantiense Concilium De Universali Ecclesiae Reformatione, Unione, Et Fide, 1473–76. Francofurti, Lipsiae: Genschius Helmestadii.

Gregorius XV. 1621. “Aeterni Patris Filius,” December.

Gregorius XV. 1622. “Decet Romanum Pontificem,” March.

“Barb.lat. 2032.” Roma, 1621. Barb.lat.2032, ff. 307r-324r. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Mentioned in Wassilowsky, Günther. 2007. “Teologia e micropolitica nel cerimoniale del conclave riformato da Gregorio XV (1621–22).” Dimensioni e problemi della ricerca storica 1: 37–55.

Visceglia, Maria Antonietta. 2013. Morte e elezione del papa: norme, riti e conflitti. L’età moderna. Roma: Viella.

“Prime porte palatii custodia alicui magno prelato vel nobili potenti, ut primum obiit pontifex, committitur, qui armata cohorte die noctuque palatium patresque tueatur, cui ducenti sive trecenti pedites assignantur.” Dykmans S.J., Marc. 1980. L’oeuvre de Patrizi Piccolomini ou le cérémonial papal de la première Renaissance. Vol. I. Livre Premier. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 29.

“Secunda custodia est in prima porta qua ad locum conclavis ascenditur. Et hec demandatur conservatoribus et capitibus regionum urbis, qui, adiunctis sibi aliquibus nobilibus civibus, portam ipsam custodiunt.“ Ivi, 29.

“Tertia custodia in secunda porta aliquanto superius, demandati solet oratoribus laicis, sive non prelatis, regum aut principum, aut etiam aliquibus magnis et potentibus proceribus numero condecenti.”. Ivi, 29-30. See also Visceglia, Maria Antonietta. 2013. Op. cit.

“Quarta autem custodia, que est in ipso aditu unico conclavis, committi consuevit prelatis dignioribus Romane curie, sex aut octo, sive sint oratores sive non, et si commode fieri potest, et alioquin idonei censeantur, curandum ut ex diversis nationibus eligantur, ut omnium studiis tractetur quod ad omnes pertinet.” Dykmans S.J., Marc. 1980. Op. cit., 30.

“Quarta autem custodia, que est in ipso aditu unico conclavis, committi consuevit prelatis dignioribus Romane curie, sex aut octo, sive sint oratores sive non, et si commode fieri potest, et alioquin idonei censeantur, curandum ut ex diversis nationibus eligantur, ut omnium studiis tractetur quod ad omnes pertinet.” Ibid.

“Turn, omnibus predictis expulsis, porta conclavis cum suo porticulo omnibus clausuris clauditur intus et extra, assignanturque claves due clericis cerimoniarum ab intus, et tres prelatis custodibus ab extra.” Ivi, 39.

That is, since the Vatican became the seat of the conclave with the election of Urban VI in 1378 after the return of the popes from Avignon.

Lombardo, Edoardo. 1959. “Incontro con Antonio Barberini gran Protettore degli affari di Francia.” Capitolium XXXIV, no. 11: 2–11. Poncet, Olivier. 2002. “The Cardinal-Protectors of the Crowns in the Roman Curia during the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: The Case of France.” In Court and Politics in Papal Rome, 1492-1700 (Cambridge Studies in Italian History and Culture), edited by Maria Antonietta Visceglia, Gianvittorio Signorotto, and Gigliola Fragnito, 158–76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wolfe, Karin. 2008. “Protector and Protectorate: Cardinal Antonio Barberini’s Art Diplomacy for the French Crown at the Papal Court.” In Art and Identity in Early Modern Rome, edited by Jill Burke and Michael Bury, 113–33. Aldershot: Ashgate. Spagnoletti, Angelantonio, and Péter Tusor, eds. 2018. Gli “angeli custodi” delle monarchie: i cardinali protettori delle nazioni. Viterbo: Sette Città.cBrancatelli, Stefano. 2012. “Dallo squadrone volante alla fazione zelante. Continuità e discontinuità nel collegio cardinalizio della seconda metà del XVII secolo.” Archivum Historiae Pontificiae 50: 13–40.

Hunt, John M. 2022. “The Market in the Conclave: Gambling on Election Outcomes in Renaissance Italy.” In The Casino, Card and Betting Game Reader, edited by Mark R. Johnson, 351–73. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Visceglia, Maria Antonietta. 1996. “La ‘Giusta statera de’ porporati’. Sulla composizione del Sacro Collegio nella prima metà del Seicento.” Roma moderna e contemporanea 1: 167–211. Hollingsworth, Mary, Miles Pattenden, and Arnold Witte, eds. 2020. A Companion to the Early Modern Cardinal. Leiden ; Boston: Brill.

“Ma essendo dette stanze [Sala Regia, Cappella Sistina, Sale Ducali] parte volte verso prati, e parte havendo lume da Cortili, si rende in esse l’aria grassa e putrefatta per la multiplicità de fiati e dell’immondezza che per essere le finestre per la maggior parte murate, non può entrar tant’aria che buona, che possa cavar la cattiva, il che ha causato nel’uscir d’ogni Conclave che de Cardinali ne siano morti molti.” Ferrabosco, Martino. “Vat.lat. 10742 - Architettura della basilica di S. Pietro in Vaticano,” n.d. Vat.lat.10742, ff.369r-384v. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana: ff. 378v-379r.

Dykmans S.J., Marc. 1980. Op. cit., 98*—99*.

The office of the “Maresciallo di Santa Romana Chiesa” had been the prerogative of the Savelli family since the Middle Ages (probably from 1270 onwards). His task was that of perpetual custodian of the Conclave. The Savelli held the office until 1712, when it passed to the Chigi family. Visceglia, Maria Antonietta. 2013. Op. cit.

“ut nullus illud intrare valeat vel exire.” Friedberg, Aemilius, ed. 1959, Corpus iuris canonici. Vol. II. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 947.

“Nulli etiam fas sit, ipsis cardinalibus vel eorum alicui nuncium mittere vel scripturam; qui vero contra fecerit, scripturam mittendo vel nuncium, aut cum aliquo ipsorum scerete loquendo, ipso facto sententiam excommunicationis incurrat.“ Ibid.

“In conclavi tamen praedicto aliqua fenestra competens dimittatur, per quam eisdem cardinalibus ad victum commode necessaria ministrentur; sed per eam nulli ad ipsos patere possit iningressus.” Ibid.

The device was introduce byy the Master of Ceremonies Paris de Grassis after Leo X election. Ceccaroni, Agostino. 1901. Op. cit., 18.

Visceglia, Maria Antonietta. 2013. Op. cit.

“Cum pervenissem in primam aulam conclavis, in eo erant circiter tria millia liominum qui nos prevenerant; nam yicecamerarius ante introitum nostrum non expulerat gentem ibidem existentem, neque viam pro cardinalibus et suis, conclave intrare debentibus ordinaverat vel custodiverat, prout ex officio sibi incumbit.” Burkhart, Johann. 1883. Diarium sive rerum urbanarum commentarii. Edited by Louis Thuasne. Vol. I. 1483-1492. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 26.

Franz Ehrle (1845–1934) was a Jesuit who became the Prefect of the Vatican Library in 1895, a position he held until 1914. In 1922, he was elevated to the rank of Cardinal. Ehrle, Franz, and Hermann Egger. 1933. Die Conclavepläne: Beiträge zu ihrer Entwicklungsgeschichte. Vol. 1–2. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Valerium et Lodovicum, Fratres Brixienses apud. Conclave reverendiss. dd. Cardinalibus pro electione novi Pōtificis paratum Romae in Palatio apostolico longe copiosius quā antea explicatū. February 3, 1550. Xilografia, 442 x 318 mm. Stampe.Cartella.Conclavi(9). Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

From the description of the conclave of 1549 by Angelo Massarelli. Ehrle, Franz, and Hermann Egger. 1933. Op. cit., 17.

Bonifacio, Natale. 1585. Vera pianta del Conclave. April 24. Bulino, 224 x 343 mm. Stampe.Cartella.Conclavi(10). Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

“Formis” indicated the activity as editor. The lettering adds “se vende alla Pace” because Van Aelst run a shop in Via della Pace, Rome. Bellini, Paolo. 1975. “Stampatori e mercanti di stampe in Italia nei secoli XVI e XVII.” I Quaderni del conoscitore di stampe, no. 26: 19–45.

Aelst, Nicolaus van. 1605. Pianta del Conclave in Sede Vacante di Leone XI et tutte le attioni che ogni giorno si fanno in Roma cominciando al di 8 di Maggio MDCV. 260 x 383 mm. Chig., Vol. 160, f. 1. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Bellini, Paolo. 1975. Op. cit., 19–45.

Rossi, Giovanni Giacomo de’. 1655. Nova Pianta del conclave fatta in sede vacante di Papa Innocentio X per elettione del novo pontefice a di 7 di Gennaro 1655. Engraving. Private Collection.

BAV, Urb. Lat. 1059/II, Avvisi di Roma, f. 303rv, 9 ottobre 1591.” Da Visceglia, Maria Antonietta. Op. cit. 2013.

Luis Felipe Flores Garzon Angela Person

Giulia Furlotti

Teresa Serrano Aviles

Tara Bissett