For many years, asylums served as vast repositories for society’s perceived imperfections; individuals deemed useless, strange, or frightening. Conceived as alternatives to prisons, they were built on the outskirts of cities, in peripheral locations where contact with the outside world was deliberately minimized.

The San Niccolò complex in Siena was the last psychiatric hospital in Italy to close permanently, on September 30, 1999. Like most Italian asylums, it was established outside the urban center, in a condition of calculated self-isolation, on the southern slope of the Santa Maria dei Servi hill. Beginning in 1858, under the direction of Carlo Livi, the Sienese asylum village was organized according to a pavilion-based model. Most of the buildings were designed by architect Francesco Azzurri and carefully distributed along the hillside to take advantage of the topography, giving the impression of a self-contained citadel.

Within this complex, the Conolly Ward — intended to house the so-called “clamorous” patients, that is, those who were the most difficult to manage — is, together with the prison on the island of Santo Stefano, the only realized example of a panopticon in Italy. This typological invention, conceived in 1791 by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham to maximize the surveillance of a space — be it carceral, medical, educational, or industrial — by a single observer, finds its Sienese transcription in a structure now in a state of total abandonment. Completely excluded from the life of the city despite its intra-moenia location, it stands awaiting a paradigm shift in its relationship with a landscape that observes it, yet fails to truly see it.

[…]

mi guarda Siena

da dentro la sua guerra,

mi cerca dentro con gli occhi

addannati dei suoi veliti

percossa dai suoi tamburi

trafitta dai suoi vessilli

e non vede me

non vede in me la mia infanzia

che di lei fu piena.

Mario Luzi1

In this excerpt, included in Per il battesimo dei nostri frammenti and published in 1985, Mario Luzi evokes the moving relationship between a city and what can confidently be assumed to be one of its own inhabitants. The city that sees everything: yet it does not see him, not his childhood, nor his memories. It does not perceive the substance of that generous bond which, according to a necessarily one-sided logic, connects the memory of a city to those who have lived within it. It does not see him because, perhaps, he is hidden or removed, confined, and thus rendered invisible.

This powerful and melancholic image has been chosen to describe and introduce a particular form of exclusion that took shape in Siena between the city and the psychiatric hospital of San Niccolò. A coexistence which, following the harsh logic that "the insane must be treated well, but kept locked away"2, acquired from its very origins the characteristics of a deliberately orchestrated urban confinement, a condition of being together, yet isolated.

Among the oldest and most prestigious institutions in Siena, the Compagnia della Madonna operated in the underground spaces of the Santa Maria della Scala hospital, directly opposite the cathedral, since the early 13th century. Born from the merger of pre-existing confraternities, it was granted legal personality by the Republic of Siena in 1363, thereby enabling it to receive inheritances, bequests, and donations. By the end of the 14th century, the Compagnia had become the most active, wealthy, and powerful among all confraternities in the Sienese state.

Over the centuries, this institution engaged in a wide range of activities: those directly or indirectly connected to religious worship, social interventions, and welfare initiatives such as the administration of hospitals, the awarding of scholarships and study prizes, and even the management of prisons. After the fall of the Republic of Siena, the Compagnia della Madonna managed to survive successive governments, remaining intact even during the Napoleonic era. Following the abolition of lay confraternities ordered by Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo in 1785, the Compagnia changed its name to Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni, a name still in use today, transforming itself into an organization dedicated to charitable works.

From the second half of the 18th century, under the reformist policies of the Grand Duchy, many aspects of civil life were restructured, including the treatment of the mentally ill. Until then, madness had not been considered curable in any meaningful way, and thus there had been no real practice of administering therapeutic care. Moreover, prior to this paradigm shift, in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, as elsewhere in Europe, so-called ‘madmen,’ and particularly those classified as ‘violent’, were handled in much the same way as criminals: through confinement. The asylum functioned essentially as a prison.

In 1757, the Florentine government ordered Siena to identify a suitable location for housing the mentally ill, and five years later, a temporary facility was established in a house owned by Santa Maria della Scala near Porta San Marco3, at the city’s southwestern edge. The operational costs of this small Ospedale de’ pazzerelli were covered by the Monte dei Paschi bank and partially by revenues from the grain flour tax. Following the bank’s financial difficulties and the abolition of the grand ducal tax, the hospital’s management was taken over by the thriving Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni4. From that moment and well into modern times, the connection between the ‘custody of the insane’ and the Pie Disposizioni remained constant in Siena.

A decree dated August 31, 1803, issued by the government of the Kingdom of Etruria, required the Società to open a second facility on Via della Fontanella, known as the Ricovero del Bigi, to temporarily house the ‘alienated’ from the provinces of Siena and Grosseto, for the purpose of confirming their mental illness and selecting patients for transfer to the Bonifazio Hospital in Florence, established in 1788. However, due to the congestion of the Florentine facility, the Sienese Ricovero was soon converted into a small residential asylum itself.

Determined to find more suitable premises for the care of Siena’s mentally ill, Marquis Angelo Chigi, then Rector of the Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni, in 1815 secured the transfer of the former convent of the Clarissan nuns of San Niccolò5, built between 1346 and 1363 and recently suppressed by the French. The asylum was inaugurated on December 6, 1818, and initially accommodated 34 patients from the provinces of Siena, Arezzo, Livorno, Pisa, Grosseto, and Massa.

Under the direction of San Niccolò’s first administrators — Giuseppe Lodoli (1818–1823), Gasparo Mazzi (1823–1833), and Pietro Tommi (1833–1857) — no significant innovations were introduced in patient care, aside from the abolition of chains and a partial introduction of agricultural labor. However, with the arrival of Carlo Livi — the undisputed protagonist of the new Italian psychiatry6 —, who directed the institution from 1858 to 1874, the asylum became a site of experimentation in patient management, with direct implications for the role of architecture in this process.

In a 1858 letter, Livi — newly appointed as the asylum’s medical director — described the facility as a “hive bristling with narrow corridors and more or less gloomy cells” 7and wrote: “It did not take me long to realize that what the asylum most needed was an asylum itself”8. With these words, he outlined a clear programmatic shift aimed at investing in a substantial redesign of the intra-mœnia structure of the complex.

From the words of Titus Burckhardt we learn that

In the ‘sacred’ construction of the city of Siena, two stages or phases can be discerned: the first is evident in the image of the old city gathered around the Cathedral […] the second is reflected in the placement of the convents and their churches, which, isolated like outposts on the extreme edges of the city’s three districts, stand guard: San Francesco to the east, San Domenico to the west, Sant’Agostino to the south, and Santa Maria dei Servi to the southeast. The presence of these monastic churches at the city’s outermost edge, though still within its walls, bears witness to a time when monastic asceticism, previously kept deliberately distant from urban life, was brought into the heart of the city9.

While most Italian asylums were typically built outside urban centers, in open countryside not far from cities, allowing for future expansion of the facilities, San Niccolò seems to have confirmed the intra-mœnia settlement logic typical of Siena, as described by Burckhardt.

Located on the southern slope of the hill of Santa Maria dei Servi, within the city’s defensive walls and near Porta Romana, the asylum first occupied the former convent and, through nineteenth-century expansion efforts, came to saturate a significant portion of what has been known since the Middle Ages as the Valle di Montone. This name refers to an area included in the urban expansion of the late thirteenth century, just beyond the now-disappeared Porta all’Oliviera, and bordered to the south by the late-thirteenth-century city walls.

Beginning in 1858, under the direction of Carlo Livi, work commenced to expand the facilities of the hospital, with the dual aim of introducing new therapeutic practices and addressing the increasingly diverse needs of the patients. The asylum district inspired by Livi’s principles10 was organized according to a model that emphasized the distribution of buildings in the area downhill from Via Romana, set on various elevations and predominantly oriented westward, toward Porta Tufi. This arrangement deliberately avoided symmetry to lend the impression of a self-contained village, interwoven with internal roads connecting medical pavilions, workshops, laboratories, a library, and a pharmacy. A small, enclosed world, positioned at the margins of the city and excluded from its civic life, where the community of patients was to become economically self-sufficient through agricultural and artisanal labor performed by the inmates themselves.

Most of the new buildings erected during Livi’s tenure were designed by architect Francesco Azzurri11 between 1865 and 1893. Appointed by Count Angiolo Piccolomini on behalf of the Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni, after gaining recognition as the designer of the Santa Maria della Pietà in Rome, Azzurri, even if not in the initial plan presented12, it eventually aligns with Livi’s vision entirely. He summarized his design philosophy for the Siena project as follows:

As a result of some of my studies, I proposed a plan for an asylum which I called a Village, as it was based on the apparent complete freedom of the patients in the open countryside and on the scientific distribution of the various sections in the manner of a village. I had become convinced that an asylum should have nothing in common with a hospital for ordinary illnesses13.

In the 'multiform'14 urban fabric of Siena — “a city that unfolds along the ridgelines of three hills that branch out like the veins of a leaf, so that from any panoramic point one looks across to what seems an entirely different city”15 — the hill of Santa Maria dei Servi, now burdened by the new volumes of the San Niccolò asylum complex, accentuates this sense of estrangement.

Set at the highest point, the most prominent structure in both scale and symbolic weight is Palazzo San Niccolò. This is the only building clearly visible from the city, as it aligns in elevation with both the city walls and the monumental complex of Santa Maria dei Servi. This imposing structure — designed by Azzurri in a neo-Renaissance style that appears out of scale with the surrounding district when viewed from the opposite ridges — underwent three distinct phases of transformation. The first phase, from 1818 to 1870, involved the acquisition and adaptation of the pre-existing San Niccolò monastery without major volumetric increases16. The second phase saw the new building extend toward the Servi complex, beginning in 1870 under Azzurri and Livi. Finally, the third phase marked the definitive spatial relationship between the old and new constructions. According to Azzurri,

the building, with a façade ninety meters wide and wings extending sixty-two meters, composed of two upper stories above a ground floor, was designed to accommodate, alongside all general services, five hundred patients of both sexes.

He envisioned it as “bearing the appearance of a grand villa palace […] with its front opening onto a garden park,” to avoid reproducing “the melancholy character of a lunatic asylum”17.

In 1873, construction began on a road linking the asylum’s inner courtyard to the convent of the Servi, which had been partially deconsecrated and was already being used for medical purposes. This intervention marked the first step in the broader urban reorganization of the asylum complex, which over the years ‒ under the leadership of Ugo Palmerini (1874–1880) and Paolo Funaioli (1880–1907), both disciples and continuators of Livi’s vision18 — expanded further with new buildings and roads, creating a space where patients could lead lives nearly indistinguishable from those of the “sane”, with ample freedom of movement across the various facilities.

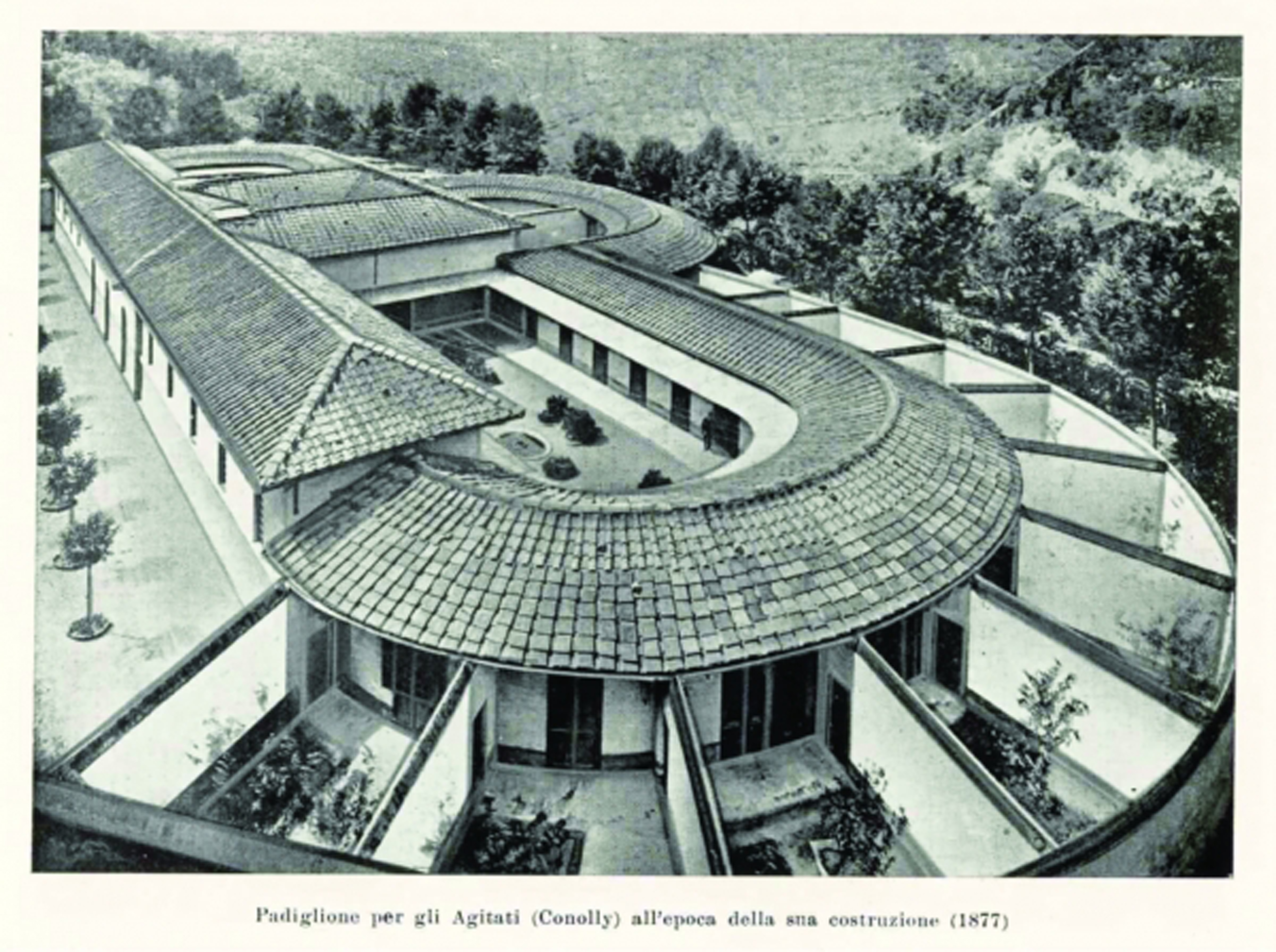

All patients were housed in the central building, with the exception of the ‘agitated’ individuals, for whom the Conolly Pavilion was built in 1877. Though less imposing than the Palazzo, this single-story pavilion with three courtyards and a raised central section19 is arguably the most distinctive and original structure within the entire asylum complex. Its spatial logic is understood as a mediated transcription of Bentham’s Panopticon20 and its placement, perched above the Orto de’ Pecci, the Porta Tufi hill, and the southern valley stretching toward Mount Amiata beyond the city walls, gives it a strikingly isolated character. The pavilion was explicitly designed to accommodate the ‘clamorosi’, the most agitated and difficult-to-manage patients.

A synthesis of functional design and adherence to the typological canons of psychiatric detention facilities of its time — both in the layout of detention cells and service spaces, and in its unusual form — the Conolly, at the time of its construction, was a critical “alien” element in the larger project of expanding and diversifying the functions of the asylum’s self-contained village21.

There are so many things that I don't understand

There's a world within me that I cannot explain

Many rooms to explore, but the doors look the same

I am lost, I can't even remember my name22.

The structure designed by Azzurri represents one of only two examples of the Panopticon model ever built in Italy, a typology conceived in 1791 by the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the form of a circular ring-shaped building, intended to maximize spatial control by a single individual. Defined by Michel Foucault as a “utopia-program"23 the Panopticon was originally not intended solely for prisons, but also for hospitals, schools, factories, and poorhouses. Its purpose was to maintain constant surveillance over its occupants, who, aware they were always being watched from a central control tower, were themselves unable to see the observers. Looking out from within the detention cells, with their identical, inaccessible doors radiating in fan-like symmetry — often multiplied on several levels — was meant to induce in the inmate a deep sense of disorientation and powerlessness. The underlying principle was a repressive mechanism, aimed at a total reform of society by conditioning behavior and optimizing control through architectural form, accomplished by a single gaze.

Order was insured in this system through the lateral division between the cells, which eliminated communication between the confined and therefore rendered the possibility of an uprising impossible. The overseen lived in a form of isolated togetherness. In the Panopticon model, there is no seeing-being seen dyad; the periphery is clearly the observed and the center the observer. This is proved not only by the size of the openings which permitted an unobstructed view of the cells while maintaining the central tower virtually opaque, but also by the fact that the tin speaking tubes that were devised by Bentham as the acoustical analogues to the visual arrangement were soon discarded because their effect was reversible and therefore not in tune with the mono-directionality of the spatial arrangement. Thus, space becomes segmented, frozen, and dead, and each individual is fixed in his place. It is interesting to highlight that “despite the presence of positions of supremacy in society, both the overseer and the overseen are trapped within the machine of the Panopticon”24. Even if we are to accept the fact that the overseer does not need to be present in the observation tower because his implied presence is enough to guarantee order, the symbol of his power is still trapped, doomed to immobility. As Foucault asserts, the Panopticon is a “machine in which everyone is caught, those who exercise power as much as those over whom power is exercised”25.

Bentham’s Panopticon was implemented during his lifetime in only a few cases: the Virginia State Penitentiary (1800), the Millbank Prison in England (1812), and the Pittsburgh Penitentiary (1826). After his death, numerous other detention facilities were constructed following this model26. In Italy, the only other comparable example is the Bourbon prison on the island of Santo Stefano, built between 1755 and 1795.

The pavilion designed by Azzurri for Siena constitutes a subtle reinterpretation of Bentham’s Panopticon, both in its spatial logic and its architectural solutions, enriched by generous open spaces described by the architect as follows: “on the internal square adorned with flowerbeds and greenery, […] air, sunlight, the scent of flowers, and the joyful horizon will comfort the patients’ sorrowful conditions”27. The original plan of the Siena pavilion consisted of a single-story building composed of three semicircles forming a double horseshoe layout, with cells arranged in a radial pattern — “each 3.50 meters wide, 4.05 meters long, and 4 meters high, covered with vaulted ceilings”28 each equipped with a small walled garden courtyard. The entire complex was enclosed by a high perimeter wall. A central core housed service areas and staff quarters, separating the two wings, one for male and the other for female patients. Each small cell had a door opening onto the internal courtyard and a window facing the resede, an exclusive garden portion enclosed by high walls, within which patients could move freely.

Around 1912, faced with the need to increase capacity — driven in part by the repressive climate that often labeled political dissidents as mentally ill, as recalled by the graffiti carved into the walls of some cells — plans were made to expand the Conolly ward. No longer sufficient for male patients alone, the facility required more beds; this could only be achieved by adding a floor to the central body and converting it into additional dormitories. It was during this phase that Azzurri’s careful and measured design began to unravel. Along with the architecture, the therapeutic approach itself may have started to erode. The renovations likely included the full covering of the central courtyard, with the demolition of original cells to create a portico overlooking the garden.

Another major architectural alteration was the creation of the so-called Criminal Ward, accomplished by roofing over the left-hand semicircle, effectively eliminating the small internal court and transforming that portion of the building into a kind of prison. During this same period, the outdoor spaces began to suffer neglect: the radial gardens, initially separated, were effectively merged by removing the walls between them, thereby erasing the floral-like radial pattern so clearly evident in Azzurri’s elegant original plan.

Like the mad rage of a dog that insists on sinking its teeth into the leg of a deer already dead, and keeps shaking and pulling hard at the fallen prey, so much so that the hunter gives up any attempt to calm it, a vision had taken root inside me: the image of a great steamship on a mountain, the boat dragging itself from the rivers by its own strength, climbing a steep slope in the heart of the jungle, and, amid a nature that annihilates the weak and the strong alike, the voice of Caruso silencing the pain and the cries of the animals in the Amazon forest, and muffling the birds’ song. […] And I, like in the verse of a poem in an unknown language I do not understand, find myself overcome by a profound terror29.

The image described in this excerpt from Werner Herzog’s diary, published under the title The Conquest of the Useless, is perhaps the most dramatic and epic visual icon of Fitzcarraldo: a masterpiece that earned the German director the award at Cannes in 1982.

This vision of the boat immobile on the side of the hill may help to frame a peculiar aspect of the Conolly. Observing Azzurri’s building, one can certainly say that it is a space in suspension, in more ways than one: literally between the city and the landscape, in the relationship between the actual confinement of its inmates and the partial freedom granted to all the other ‘madmen’ of San Niccolò, between the memory and oblivion of its past and present condition, between physical, tangible presence and the perpetual risk of being lost in a heap of rubble.

Unlike Fitzcarraldo’s ship, the Conolly ward was not meant to move, but to fix and immobilize. Yet both structures share a deep logic of loneliness and detachment. They are removed from the social fabric that surrounds them; they stand apart, forgotten in their remote or reclusive places, nearly invisible despite their physical presence: one in pursuit of a delusional utopia, the other in service of disciplinary rationality and utter control. What unites them is the image of the hill: an elevated terrain of control, detachment, and symbolic estrangement from the city.

The ship does not advance, does not navigate: it is still. In the frames where the protagonist, played by Klaus Kinski, is alone, dismayed, at the foot of the hill with the boat behind him, stuck there, Herzog stages an architecture of defeat, of the interrupted dream, which paradoxically becomes even more grandiose in its impotence. In these scenes, the director shows us the coexistence of misery and evocative power generated by the evident “suspension of function” brought about by the protagonist’s madness — mimic Herzog’s famous preference for an ‘ecstatic truth’ rather than pure and simple reality — a characteristic that links Fitzcarraldo’s venture to ruins, such as the Conolly: a space that has lost its purpose, and is awaiting a new poetic potential.

If it is true that “every construction only builds a collapse”30 this pavilion is today in a state of full realization of an ‘avoidable’ or ‘to be avoided’ destiny, precisely because it is the embodiment of a principle, an idea of space, constructed in ways, forms, and dimensions very different, if not unprecedented, compared to Bentham’s prototypes.

In 1978, in Italy, the entry into force of Law 180 — commonly identified by the name of its inspirer: Franco Basaglia — mandated the closure of psychiatric hospitals, reforming the mental health care system and marking a turning point in the world of psychiatric patient assistance.

However, in the history of the San Niccolò in Siena, the Basaglian movement had little impact, as patients continued to be housed there for many years, even after the property was transferred to the local health authority. After a long period of dismantling, the one in Siena was the last psychiatric hospital in Italy to close definitively: on September 30, 199931.

Following Azzurri's interventions, the expansion of the asylum village continued between 1894 and 1933, under the work of architects Vittorio Mariani and Primo Giusti32. The last phase of interventions, signed by Enzo Zacchiroli, already responsible for the headquarters of the Banca d’Italia in Siena, dates back to the early 2000s and refers to the transformation of the asylum building and laundry into university campuses, as well as the creation of a new auditorium inserted between the 14th-century walls and San Niccolò.

Today, the village houses a variety of institutions and functions: a psychiatric rehabilitation center remains, along with an oncology ward, a cooperative, some residential areas, and several departments of the University of Siena for the faculties of Engineering, Mathematics, Languages, Literature and Philosophy, and Social Service Sciences. In the valley below, the former psychiatric hospital laundry was renovated and since 2004 has hosted the Department of Physics.

Other structures, however, have fallen into disuse due to their particular structural characteristics that make it difficult to repurpose them for other functions, and they are currently in a state of abandonment. Among these is the Conolly Pavilion33. Closed definitively on January 1, 1978, currently unfit for use and heavily deteriorated by the alterations it underwent over time to meet the asylum's needs, this urban relic is a rare but nonetheless excellent witness to a historical period — the Enlightenment — which was decisive for the cultural development of Western society and modern architecture34, and it is therefore impossible not to think about preserving it.

What future can still be imagined for this graceful and measured 'observing space,' abandoned to itself on the western hill of Santa Maria dei Servi?

The former psychiatric complex, despite its change of use and the diversification of the institutions that currently occupy it, still retains the self-excluding exclusivity of its origin. No other road leads to the complex; it is entirely cut off from the Orto de’Pecci below and the adjacent hill on which the Basilica of San Clemente in Santa Maria dei Servi is located. From every side and from every point of the city, the complex is inaccessible to view. Both from Piazza del Mercato and from Orto dei Tolomei, adjacent to the Monastery of Sant'Agostino, on the hill facing San Niccolò, it is impossible or almost impossible to understand the layout of the former hospital or to glimpse its buildings. It is a part of the city that even the citizens themselves do not know well or visit, despite the value of the architecture within. To this day, the only access road to the complex is the one from above, coming from Via Roma.

The Conolly ward still shares the same paradoxical inability to communicate and relate to the outside. Also a child of Siena, from its confinement in the Valley of Montone, it seems to say, as in Luzi's words, ‘the city looks at me and does not see me’.

If one were to imagine a future for this guilty neglect, one could only hope for a return of this space to dialogue with the landscape, expanding the scale of a desirable recovery intervention from the architectural to the urban, making this piece an exemplary part of a cohesive whole.

If in the original model by Bentham the periphery is clearly the observed and the center the observer, the new relationship that the structure should establish with its surrounding context could attempt a reversal of perspective: proceeding with a rewriting of the constricting gaze, directed inward, exclusive, typical of the panopticon that Foucault defines as the “eye of power”35 into one of a free nature, directed outward, inclusive, and thus contemplative.

Responding to a logic of double vision — where the subject who looks is both observer and observed — by dialoguing with the monuments or the landscape to the south, the Conolly would finally quell that desire to be recognized which, if it is an inseparable condition of being human to recognize oneself as a person — "persona originally means 'mask' and it is through the mask that the individual acquires a role and social identity"36 — could also represent for this work a new season of overcoming its condition as an excluded. If exsistere means "to be outside oneself", or 'to be' because 'recognized by the other,' the Conolly, by opening up to the city, would initiate an unexplored process of knowledge in its history, avoiding the oblivion of neglect and the consequent risk of an irrecoverable "loss of identity"37.

By radically changing the centripetal logic of the pavilion, rewriting its relationship with the context according to a centrifugal logic, the need to bring a marginal, exiled place back to a ‘finally’ central importance for Siena would materialize; opening its gaze to the city "full of houses and reddish towers"38 and to that extraordinary gorge leading to the Val d'Orcia, described by the fellow poet Luzi in Nel corpo oscuro della metamorfosi as: "[...] red sea / of washed clays / [...] pointing to the heart of the enigma"39.

This paper builds owes its beginning to Arianna Fusi’s Master’s thesis on the design reinterpretation of the Conolly Pavilion (February 2022, under my supervision), expanding its scope through a broader historical and critical framework.

notes

Luzi, Mario. 2001. “Bruciata la materia del ricordo.” In Tutte le poesie, 607. Milano: Garzanti. Trad. by the author: “[…] Siena looks at me / from within her war / she searches within me with the damned eyes / of her young warriors / struck by her drums / pierced by her banners / and she does not see me / does not see in me my childhood / that was full of her”.

Conolly, il manicomio dimenticato. Accessed March 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IAnGq33vQOI.

Leoncini, Alessandro. 2007. “Per la storia delle origini del manicomio di Siena.” In San Niccolò di Siena: storia di un villaggio manicomiale, edited by Francesca Vannozzi, 58. Castelvetrano: Mazzotta.

Renato Lugarini. 2007. “Il San Niccolò e la Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni.” In San Niccolò di Siena: storia di un villaggio manicomiale, edited by Francesca Vannozzi, 67. Castelvetrano: Mazzotta. Archive of the Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni di Siena, p.137. Accessed February 2025. https://cartedalegare.cultura.gov.it/fileadmin/redazione/inventari/Siena_OP_SN_PieDisposizioni.pdf.

Colucci, Silvia. 2007. “Il San Niccolò di Siena da monastero francescano a villaggio manicomiale: storia, architettura e decorazione (1810- 1950).” In San Niccolò di Siena: storia di un villaggio manicomiale, edited by Francesca Vannozzi, 80. Castelvetrano: Mazzotta.

Giannetti, Anna. 2013. “Manicomio di San Niccolò di Siena.” In I complessi manicomiali in Italia tra otto e Novecento, edited by Cesare Airoldi, Maria Antonietta Crippa, Gerardo Doti, Laura Guardamagna, Cettina Lenza, Maria Luisa Neri, 199. Milano: Electa.

Vannozzi, Francesca. 1991. “La vicenda manicomiale senese in un manoscritto di Carlo Livi.” Revue Internationale d’Histoire ed Métodologie de la Psychiatrie, 3: 47.

Ibid.

Burckhardt, Titus. 1999. Siena Città della Vergine. Milano: SE, 73.

The village was intended to function as a simulacrum of the real city, separate and inaccessible, where each patient was assigned a task, usually manual and, at least in principle, the same as the one they had performed before being admitted, predominantly in agriculture and craftsmanship with the goal of “bringing the mentally ill back as much as possible to the ordinary conditions of social life” through work (ergotherapy). Colucci, Silvia. 2007. Op. cit., 82.

Francesco Azzurri was an architect born in Rome in 1827, he was the nephew of architect Giovanni Azzurri (Rome 1792–1858). A representative of the Neo-Renaissance tradition — except for the eclecticism of his later phase, which includes the Palazzo del Governo of the Republic of San Marino (1894) in neo-medieval style — Azzurri was responsible for several significant projects in the field of hospital architecture. Among his most notable works are: the Santa Maria della Pietà Hospital in Rome (1862); the Fatebenefratelli Hospital on Tiber Island (1867); and the asylums of Siena and Alessandria. In 1880, he has been president of the Accademia di San Luca.

Giannetti, Anna. 2013. Op. cit., 199.

Azzurri, Francesco. 1892. Manicomio di San Niccolò, Siena: Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni, 3.

Burckhardt, Titus. 1999. Op. cit., 15.

Ibid.

This became necessary around 1868, when the insane from the provinces of Arezzo, Pisa, Livorno, and Grosseto were transferred to Siena, causing the patient population to rise from 383 to 729, rendering the old facilities hopelessly outdated.

Azzurri, Francesco. 1892. Op. cit., 3.

Colucci, Silvia. 2007. Op. cit., 87.

Modified by architect Vittorio Mariani in the 1934.

Bentham, Jeremy. 2009. Panopticon ovvero la casa d’ispezione. Venezia: Marsilio; Loche, Annamaria. 1991. Jeremy Bentham e la ricerca del Buon Governo. Milano: Franco Angeli; Belloni, Ilaria, and Paola Calonico, eds. 2023. Un dialogo su Jeremy Bentham. Etica, diritto, politica. Pisa: ETS.

Following the construction of the Conolly, other facilities were added: a ward for idiots and imbeciles — the Ferrus, later renamed Forlanini —; the Villa delle Signore, or women’s ward; the laundry; the workshops; the Kraepelin, for patients assigned to agricultural labor; and the workshops. The Pharmacy (1885), built in a Neo-Pompeian Neoclassical style based on a design by Azzurri, was constructed almost entirely through the labor of four patients. Giannetti, Anna. 2013. Op. cit., 201.

Excerpt from the lyrics of the song: "Within" By Daft Punk Featuting: Chilly Gonzales, in Daft Punk, Random Access Memories (2013). Thanks are due to Angelo Lavanga for suggesting it, during a conversation about the ADHj Call, the topic of exclusion and its forms.

Barou, J.P., and Michelle Perrot, eds. 2009. “L’occhio del potere. Conversazione con Michel Foucault.” In Panopticon ovvero la casa d’ispezione, edited by Jeremy Bentham, 23. Venezia: Marsilio.

Lucas, Pavlina. "Panopticon, the Prison and Modernity". Accessed February 2025. https://www.pavlinalucas.com/1993-2010/panopticon.html.

Barou, J.P., and Michella Perrot, eds. 2009. Op. cit., 19.

La Monica. Marcella. 2014. Dal Panopticon di Bentham a modelli parzialmente panottici. Prigioni tra Settecento e Ottocento. Palermo: Pitti Edizioni.

Colucci, Silvia. 2007, Op. cit., 88.

Ibid.

Herzog, Werner. 2007. La conquista dell’inutile. Milano: Mondadori, Prologo.

Yourcenar, Marguerite. 2014. ‘Anna, Soror…’ In Come l’acqua che scorre. Tre racconti, 55. Torino: Einaudi.

Accessed March 2025. https://www.nuovarassegnastudipsichiatrici.it/volume-18/30-settembre-1999-chiusura-san-iccolo#:~:text=L'ospedale%20psichiatrico%20San%20Niccol%C3%B2,oggi%20sede%20di%20numerose%20attivit%C3%A0.

Cfr. San Niccolò da Convento a Manicomio, Autore scheda: Contrada di Valdimontone, Andrea Ciacci, Beatrice Pianigiani. Accessed March 2025. https://www.valdimontone.it/home/archivio/a-spasso-per-il-rione/san-niccolo-da-convento-a-manicomio/. Colucci, Silvia. 2007, Op. cit., 87.

It is interesting to note that the ward designated for the segregation of agitated patients at the San Niccolò psychiatric hospital was named after the English psychiatrist John Conolly, the pioneer of the no-restraint system that is, the complete absence of any form of physical restraint; as stated in: Conolly, John. 1856. Trattamento del malato di mente senza metodi costrittivi. Torino: Einaudi.

Pavlina, Lucas. "Gropius | Le Corbusier : The Two Faces of Modernism". Accessed february 2025. https://www.pavlinalucas.com/1993-2010/modernism.html.

Barou, J.P., and Michelle Perrott, eds. 2009. Op. cit., 7-30.

Agamben, Giorgio. 1999. Identità senza persona in Nudità. Roma: Nottetempo, 71.

Ivi, 72

Burckhardt, Titus. 1999. Op. cit., 15.

Luzi, Mario. 2001. "Nel corpo oscuro della metamorfosi." In Tutte le poesie, 382. Milano: Garzanti. Original vers: “[…] mare rosso / di crete dilavate / […] che punta al cuore dell’enigma”.

Gjiltinë Isufi

Luis Felipe Flores Garzon Angela Person

Ginevra Rossi

Teresa Serrano Aviles