Virginia Woolf once wrote that street haunting in London was among the “greatest of pleasures”. Can we today say the same? Or, on the contrary, is it true that, as it has been said, a woman’s place is not in the city?

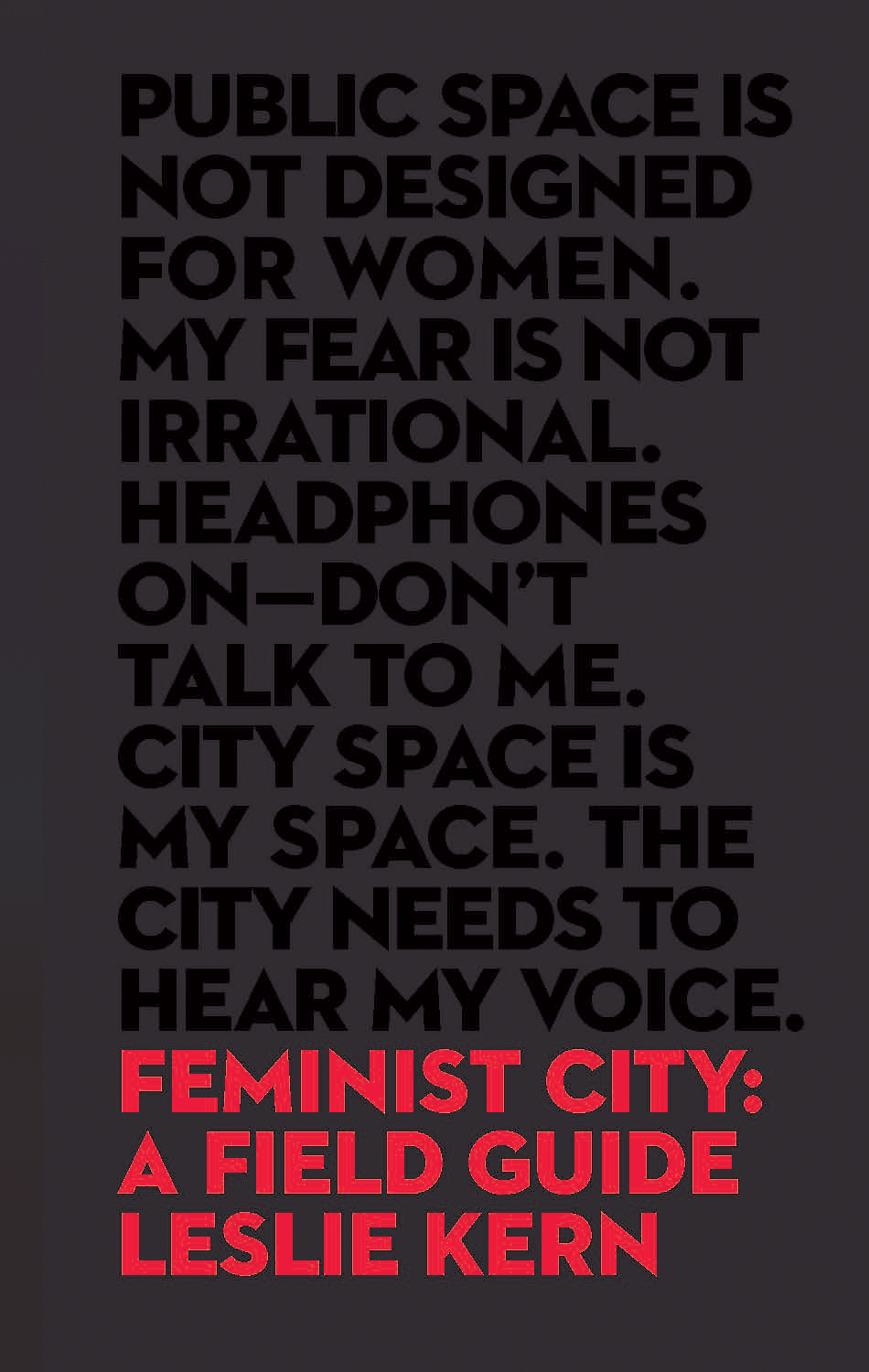

Written by Leslie Kern, Associate Professor of Geography and Environment and Director of Women and Gender Studies at Mount Allison University, Feminist City stands as a compendium of author’s personal experiences (between London, Toronto, New York, and other cities), various studies, and academic works. The main topic focuses on the forms of oppression and urban injustices faced by women, as well as the recognition of the right to the city.

The book structure reveals that today’s city is a minefield and the city of men (introduction), the city of moms (chapter 1), the city of friends (chapter 2), the city of one (chapter 3), the city of protest (chapter 4), the city of fear (chapter 5), the city of possibility (conclusions). All these cities, however, coexist in the general belief that the city as a physical entity should empower everyone. The suggestion that emerges is, in fact, to reshape the city, following the model of Wien (“gender mainstreaming” concept applied in urban planning), for example, with its housing developments newly imagined by feminist designers, which includes on-site childcare, access to transit and health services.

While revealing their gendered implications and drawing on second-wave feminism, the book dissects how women experience cities differently than men by confronting many urban practices.

The pages, hence, deeply analyze stereotypes and racial effects caused, among other things, by the increasing development of suburban areas, which became good places for women and children already according to Jane Jacobs 1960’s theories.

Taking up Baudelaire’ and Simmel’s image, the city has been designed, from its foundation, for flâneurs, white and able-bodied men. The barriers through which women inhabit the city are not only physical, but also psychological, social, economic. Among the physical constraints, Kern highlights spatial forms of exclusion. In this regard, the experiences of disabled people in a wheelchair or the one of a new mom who tries to move around the city are frustrating, despite the inaccessible or inoperative elevators in the underground [“stairs, revolving doors, turnstiles, no space for strollers, broken elevators and escalators, rude comments, glares”, p. 39]. Trapped in a body that becomes “a big inconvenience to others” [p. 29], the disappointment of moms includes also social hostilities embedded by the city, where freedom turns into a distant memory and the metropolis becomes a “physical force to constantly struggle against” [p. 33]. Other forms of segregation, moreover, are the ones generated by post-war transformations, with the developments of suburbs and problems raised by gentrification.

Furthermore, from a social perspective, there is a focus on the intersections of gender and sexuality. By quoting famous movies (Sex and the City, 1998; The Fits, 2016; Our Song, 2000; Girls Town, 1996; Beverly Hills 90210, 1990; Foxfire, 1996) and novels (Notes from a Feminist Killjoy, 2016; My Brilliant Friend, 2011), the author questions how a city should decentre the nuclear family, valuing women relationships. Friendships, in fact, shape the ways of engaging with the city itself, but are also part of the “spheres” that influence the urban spaces, such as individual space and solitude in a patriarchal environment (where wearing headphones is one way for women to claim their personal space and independence), protest, fear, motherhood.

In 2023 the chosen word of the year by the Institute of the Italian Encyclopedia Treccani was “femicide”. If we think about the trends that are sadly becoming common, the perceived city is the one described by Kern: the city of fear. Women, in fact, feel unsafe during both day and night-time, experience harassment, threats, crimes, domestic and sexual violence. Since we live hammered by dreadful events, women build “mental maps” [mapping danger, p. 121] in order to face fear and better navigate the city, limiting the use of public transport and sometimes even their work choices.

Contemporary city life offers women a freedom that is still bound by gendered norms, mainly based on older roles (private sphere, domestic, etc.). Hence, women inhabit a written city and, quoting the geographer Jane Darke, “our cities are patriarchy written in stone, brick, glass and concrete” [p. 21]. Kern insists on the fact that physical places like cities influence and mould social relations, power and inequalities and “matter when we want to think about social change” [p. 21]. At the same time, the risk of planning cities friendly to all – women and men – is that policies may not be accompanied by a commitment to redressing inequalities in caregiving and domestic work, that should not be prerogative of women only.

If being a woman in the city means “learning a set of embodied habits, mostly unconsciously” [p. 136], then Kern argues for issues and taboos that are almost invisible to architects and planners. Although on March, 7 2025 the European Commission adopted the Roadmap for Women’s Rights, a long-term vision for achieving gender equality, there is still a long way to go. Public bathrooms and restrooms, for example, should be accessible for all bodies across gender, ability and class (e.g. diaper change, spots to nurse, menstruation, etc.); some paradoxes such as the use of earbuds for personal defense, the gentrification of parenting, the stigma of the stroller, and the “pink taxes” on public transportation, make the city a barricade for women.

Exceptions of inclusive projects are the Superblocks in Barcelona, the “complete streets” in Madrid to prevent gender-based violence in public spaces, the pilot “safe zone” in the centre of Dublin, the parking spaces marked with pink lines for new mothers and fathers of kids (under two years old) emerging in Milan and Paris.

“A feminist city must be one where barriers–physical and social– are dismantled, where all bodies are welcome and accomodated. A feminist city must be care-centred, not because women should remain largely responsible for care work, but because the city has the potential to spread care work more evenly. A feminist city must look to the creative tools that women have always used to support one another and find ways to build that support into the very fabric of the urban world” [p. 52], writes Leslie Kern. And yet, few are the the examples of cities careful to women’s needs, where harassment, crimes and violence are mere words and not established practices [“There are little feminist cities sprouting up in the neighbourhoods all over the place, if we can only learn to recognize and nurture them”, p. 143]. Thus, this book reminds us that the feminist city is still an ongoing experiment and, unfortunately, not a fixed masterplan.

NOTE: Any reference to precise pages in the text comes from the 2020 edition, published by Verso Books.

Feminist City. Claiming Space in a Man-made World

Leslie Kern

Between the Lines, Verso Books

Toronto, London, New York

2019 (first edition), 2020, 2021

19 x 12 cm

216 pages

English

9781771134576

Pages from Leslie Kern, Feminist City. A Field Guide, 2019. © Courtesy of the Publisher Between the Lines.