Among places historically closed to the city, monasteries and convents have an emblematic role. In his famous De re aedificatoria (1452), Leon Battista Alberti wrote “Pontificis castra quidam sunt clausura” (“the stronghold of the religious is the monastery”). The seats of religious orders stood as large, impenetrable and autonomous building volumes, located in the heart of the city.

During the reign of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria (1740-1780) and her son Joseph II (1780-1790), these places, mostly closed to the community, were taken by the State from the control of the Church and put at the service of the “public good”. Aligned with the new Enlightenment ideas, these rulers financed the construction of public buildings not just for cultural enrichment, but also altruistic care for a vast range of groups in need – from orphans and widows to the unemployed and mentally ill.

This was possible thanks to the abolition of religious orders and brotherhoods and the confiscation of their assets: income, land, precious goods, and above all property – the latter of which was often typically well suited to the activities necessary for modern social transformation due to the spatial characteristics of its unique typology: dimension, position, and distribution, which were made even more favorable thanks to the monastery’s auspicious separation from the city.

The case of the territory known as Austrian Lombardy (including the territories of the former duchies of Milan and Mantua) is of particular interest, as it constituted the first “laboratory” of religious reforms both in relation to the rest of the Habsburg Empire and to the other pre-unification states of the peninsula (more involved by the Napoleonic suppressions).

Since 1768, in Milan, Pavia, Lodi, Cremona, Como, Casalmaggiore and Mantua the first monasteries were suppressed, and, after careful evaluations regarding the “public decorum”, expertly repurposed by the selected chamber architects into hospitals, prisons, workhouses, orphanages, public schools, and administrative offices. Thus began the process of transformation of “Pontificis castra” to places for the “Public good,” which would continue for the next 200 years.

Religious architecture has historically represented one of the most emblematic spatial forms of exclusion. In early modern urban contexts, monasteries and convents constituted separate worlds: spaces physically and symbolically isolated from civic life. As Leon Battista Alberti wrote in De re aedificatoria (1452), “Pontificis castra quidam sunt clausura” – the monastery as a fortress of the sacred, walled and autonomous1.

This article explores the persistence of the claustrum – the space of monastic enclosure – even after its transformation into public infrastructure. Through archival and bibliographical sources, and adopting a typological and territorial approach, the essay analyses the case of Austrian Lombardy as an early laboratory for the secularization of urban welfare in the modern era.

Retracing the spatial and institutional conversions in the main cities of Lombardy, particularly in Milan, the investigation questions fractures and continuities: to what extent were these once-exclusive spaces truly opened to the public? And what symbolic, architectural, or regulatory remnants of religious enclosure continued to operate in their new uses?

By bringing to light the spatial and cultural legacies of these transformations, this study contributes to the contemporary debate on the intersection between architecture, memory, and mechanisms of governance, offering a reflection on how exclusion can survive even within architectures seemingly oriented toward inclusion.

The term claustrum, from the Latin claudere (to close), evokes an architectural and existential condition of separation. In the monastic tradition, it did not refer only to the cloister as a physical element, but designated an entire regime of regulated and ritualized isolation. As prescribed by the rule of the order, the claustrum was the space of enclosure, intended for prayer, meditation, and self-surveillance, and it represented the daily horizon of religious life. One did not enter it by chance: one entered by vocation, and once inside, the rule dictated time, gestures, and silences2.

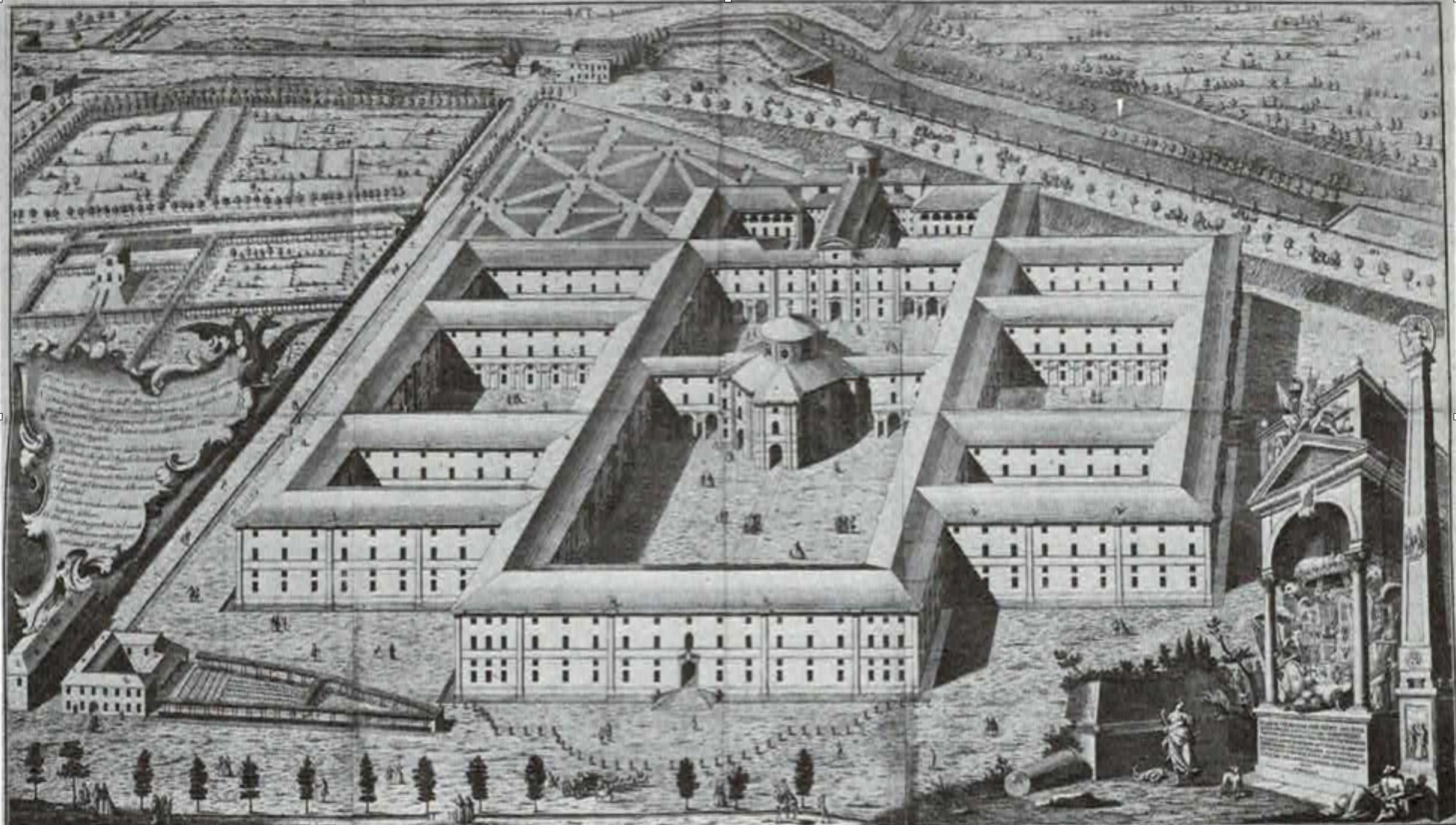

The cloister, the central element of the conventual structure, assumed a significance that was not only functional but also symbolic, forming a spatial translation of theological and disciplinary principles. Its centripetal and repetitive geometry, often organized around a central garden, structured an existential experience aimed at interiority. The architectural configuration was designed to foster contemplation, isolation from the external world, and discipline of the body and senses. Every part of the conventual space – from dormitories to refectories, from libraries to oratories – was conceived to reinforce separation from the secular world and promote the regularity of spiritual life (fig. 1)3.

Over time, this architectural logic produced highly codified forms. Monasteries were established in the heart of cities without ever blending into them: enclosed enclosures, easily identifiable, but inaccessible. Elements such as massive perimeter walls, elevated and screened openings, and the internal separation of pathways between monks and laypeople all contributed to defining a spatial device aimed at segregation and limiting visual and functional permeability. In the case of female monasteries, an additional barrier was added: that of the male gaze, further reinforcing the condition of marked isolation for religious women4.

This symbolic condition – being “other,” separate, inaccessible – survived even when, in the 18th century, the Enlightenment began to question the ideological legitimacy of monasticism. Whereas the claustrum had once been justified by divine law, it now came to be seen as an obstacle to the rationality of urban space, to the efficiency of the State, and to the principle of social utility. The architecture itself became a target of critique: what had once been sacred closure was now suspect; invisibility, historically associated with spiritual purity, began to be interpreted as a sign of social unproductivity and organizational inefficiency5.

Yet it was precisely in this phase of deconstructing the convent system that the claustrum demonstrated surprising resilience. The very qualities that had defined monastic isolation – functional autonomy, internal order, physical separation – made it an ideal container for the new uses envisioned by the Habsburg reforms: hospitals, asylums, penitentiaries, orphanages, schools, but also factories, barracks, and offices. The architecture of separation was not demolished, but reconfigured: spiritual control became social control; moral surveillance became medical or disciplinary surveillance6.

The claustrum did not disappear: it survived materially, spatially, and ideologically. Its logic was reinscribed in the new institutions of care and control. As Michel Foucault has shown, modernity does not destroy mechanisms of exclusion but reformulates them: it secularizes them, institutionalizes them. The former monastery, now a place of care or confinement, continued to separate, to silence, to regulate7.

Thus, the architectural space originally intended to protect the soul from the contamination of the world became a device for containing the marginal figures of the new society: the insane, the poor, criminals, and orphans. The memory of enclosure, far from being erased, is etched into stone and continues to operate. Modernity did not dissolve the claustrum, but secularized it.

In late 18th-century Austrian Lombardy, spaces of religious enclosure underwent an unprecedented political and institutional transformation8. The economic and demographic crisis following the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) struck the Habsburg Empire hard: severe human losses, a rise in widows and orphans, famines, and a drastic decline in births left a deep mark on both urban and rural populations9.

In this dramatic context, the court of Vienna launched a vast program of administrative and fiscal reforms aimed at strengthening state control and regenerating imperial finances10. More peripheral territories such as the Austrian Netherlands, Hungary, and especially Lombardy were called upon to contribute new resources to an empire that was weakened but still ambitious.

The so-called Austrian Lombardy – comprising the State of Milan and the former Duchy of Mantua – presented itself as a territory marked by administrative disorder and deep social inequalities, inherited from previous governments. The central authority struggled to impose itself on a local system dominated by noble incomes, ecclesiastical immunities, and a large and entrenched clergy. Illiteracy, unemployment, urban crime, and widespread poverty weighed on a state that lacked adequate tools to intervene11.

It was in this scenario that the monarchy promoted a plan to rationalize fiscal and bureaucratic structures, under the leadership of Chancellor Anton von Kaunitz and Count Carlo Firmian, plenipotentiary of Lombardy12. The adoption of a unified currency, the liberalization of trade, and the improvement of infrastructure enabled an acceleration of economic activity13. Farmers and entrepreneurs, attracted by new opportunities, invested in manufacturing and agriculture, also aided by land reforms and the alienation of ecclesiastical property14.

Within this framework of state reorganization, the convent system became the target of a focused reform effort. Religious orders, long accused of economic uselessness and social inefficiency, were viewed as obstacles to the Enlightenment project of rationalization and public utility. Convents, with their tax-exempt incomes, opaque property management, and tendency to shelter individuals removed from productive labor, were seen by the State as contrary to good governance15.

Suppressions, initiated under Maria Theresa and radicalized by Joseph II, were justified not only as economic measures but also as actions of public order and moral reform16. Between 1768 and 1790, dozens of conventual complexes in Lombardy were dissolved, alienated, repurposed, or auctioned off. The resulting release of real estate generated a true “spatial” reform of Lombard cities17.

On the surface, this appeared to be a shift from sacred space to the common good, from enclosure to collective service. Yet, upon closer examination, the process was far from linear. The spatiality of the enclosure was not always eliminated: sometimes it survived, incorporated into new uses; other times, it was symbolically reproduced in different forms. The State's self-representation, even with inclusive aims, often adopted architectural codes and devices rooted in separation and control18.

The introduction of state welfare in Lombardy was the joint result of an ideological shift and the implementation of a systematic and rationally planned technical-administrative apparatus19. Between 1767 and 1786, the Austrian monarchy deployed an operational machine of extraordinary efficiency: the Giunta Economale per le materie ecclesiastiche e miste, tasked with reclassifying, rationalizing, and redistributing religious assets according to principles of public utility.

Under the direction of Firmian and the supervision of Kaunitz, the Giunta operated as a true institutional reorganization unit, anticipating practices typical of the modern administrative state20. Its main operational tool was the so-called Piano di sussistenza, drawn up in collaboration with ecclesiastical authorities but based on objective parameters: numerical consistency, financial sustainability, internal discipline, and the potential use of assets for civic purposes. The language adopted was technical, not moral: expressions like “disorder,” “uselessness,” “redundancy,” and “profitability” reflected a secular approach to the management of the sacred21.

Initially, the closure of convents followed a selective logic based on numerical and territorial criteria: priority was given to small convents in minor towns, especially those with fewer than twelve religious members. Beginning in 1769, the first closures took place: buildings were visited, inventoried, and their movable and immovable property alienated, rented, or auctioned22. The procedure included settling any debts contracted by the suppressed communities and granting pensions to expelled religious members. However, the core of the operation was the efficiency of reuse: urban spaces – already built, autonomous, and centrally located – were quickly reassigned to new public functions.

The suppressions unfolded in two distinct phases, corresponding to the reigns of Maria Theresa (1740–1780) and Joseph II (1780–1790), and they marked a crucial turning point in the institutional transformation of the territory. In the first phase, the policy was implemented cautiously: closures mainly affected smaller male communities, with systematic exclusion of female orders23. It was under Joseph II that the policy became systematic and centralized: all contemplative orders were abolished, regardless of gender or function, and their assets were absorbed by the State and redirected toward public utility24.

Reuse strategies varied according to the political and institutional role of each city. In Milan, the administrative capital of the Kingdom, reuse followed a logic of civic centralization: between 1770 and 1786, at least eighteen religious complexes were closed and transformed into hospitals, poorhouses, workhouses, orphanages, schools, archives, bureaucratic offices, or barracks25. In some cases, buildings were demolished to make room for institutions emblematic of Enlightenment modernity – as in the case of the church of Santa Maria della Scala, replaced by the theater of the same name (fig. 2)26.

In Pavia, home to the reformed university and a center of new secular culture, the approximately fifteen suppressions documented between 1773 and 1790 were oriented toward educational repurposing: convents and religious colleges were converted into seminaries, civil schools, secondary colleges, and university-related facilities, reinforcing the city’s role as the academic capital of the Lombard territory (fig. 3)27.

In Mantua, a city with a weaker civic and welfare network, reuse followed a compensatory and territorial logic. The eighteen convents taken over between 1771 and 1785 were assigned to hospitals, orphanages, popular schools, barracks, and military warehouses, helping to construct a minimal public service network. Architects such as Paolo Pozzo and Leopold Pollack were entrusted with transforming the spaces, adhering to a functional and decorous aesthetic (fig. 4)28.

A decisive turning point came with the suppression of the Order of Jesus in 1773, decreed by Pope Clement XIV29. Their assets, which were highly concentrated in urban and intellectual contexts, were explicitly converted to public educational uses: for the first time, ecclesiastical capital was directly reinvested into a state project for collective education, marking the shift from confessional to civic knowledge.

A key aspect of the entire process was the traceability of funds: the monarchy required that proceeds from alienations be reinvested in useful institutions under state control30. During the Teresian period, these funds were allocated to targeted charitable initiatives, aimed at addressing local shortcomings – particularly to benefit the poor and orphans – and to promote education in the major centers of Lombardy. Under Joseph II, these interventions became part of a more organic and territorial plan, focused on reorganizing the healthcare system and on a labor policy intended to combat poverty and crime31.

The state welfare project developed between the 1760s and 1780s cannot be reduced to a simple act of secularization: it represented a complex political and territorial restructuring that not only redefined assistance, but generated a new public spatiality – composed of repurposed buildings, administrative networks, cadastral maps, and notarial acts. Most importantly, it made visible the shift from spiritual control to state control, transforming the convent from a closed space into a monitored, secular, and productive public resource32.

The transformation of convent buildings into hospital facilities was one of the strategies favored by the Habsburg state to address the severe healthcare deficiencies in late eighteenth-century Lombardy33. In a context where existing hospitals proved inadequate – in terms of bed numbers, hygienic conditions, management capacity, and the treatment of complex illnesses – desacralized convents offered an architectural opportunity ready for reuse: solid, autonomous, walled, already designed for isolation and regulated daily life. As often emerges from the reports of the Giunta economale, the conventual typology of double-loggia cloisters made religious buildings easily adaptable to all public and collective functions34.

A technical commission composed of a physician, a surgeon, and a pharmacist was tasked with assessing the healthcare system in Lombardy. Of the eighteen active hospitals, with 2,010 beds and about 31,750 patients treated annually, only a few met the efficiency standards required by modern medicine35. “Hospitals were few and lacked beds, equipment, and services, mostly managed by the incompetent,” to the extent that they excluded “chronic patients, incurables, the insane, the rickety, and those with venereal diseases”36.

The reorganization of convent spaces was intertwined with a broader epistemological transformation: the emergence of clinical knowledge based on the separation of diseases37. Where previously a social and charitable logic had prevailed, now a classificatory rationality took hold: mentally ill, infectious, chronically ill, and venereal patients were isolated in distinct areas, each with specific therapeutic functions and behavioral rules. In this process, convent architecture was not only reused but reinterpreted: cloisters became walking spaces, cells tools for therapeutic isolation, dormitories subdivided according to nosographic categories38.

The case of Milan exemplifies a gradual evolution toward specialization. Since 1456, there had been a hospital for the mentally ill at the convent of San Vincenzo in Prato (called “dei Matti”), strategically located near Porta Ticinese. However, in 1784, the building was converted into a workhouse, and the mentally ill were moved to the former Jesuit complex of Senavra, a large site outside Porta Tosa: spacious, well-ventilated, dry, and sufficiently distant from the city (fig. 5). This choice reflected a new sensitivity toward the therapeutic environment: “considered healthy, solid, well-ventilated, dry, and sufficiently distant from the city”39.

In Pavia, the response was slower and less structured: only in 1786–87 was the former convent of Sant’Agata converted into an asylum40. Compared to Milan, the project was more modest, but it exemplified a model gradually expanding from the center to the provinces. In Cremona, the solution was even more minimal: two rooms for the mentally ill inside the Hospital of Sant’Alessio, while the main hospital was renovated with targeted interventions by chamber architect Faustino Rodi41.

Among existing facilities, the Ospedale Grande of Mantua stands out for its early adoption of the “pavilion model”: already in 1771, despite its limited size, it featured separation of patients by type of illness — a principle that anticipates modern nosological models42. The 1772 expansion included “several small rooms intended for the insane,” demonstrating an awareness of mental illness absent elsewhere. Additionally, a later project by Piermarini planned the transformation of the entire facility according to principles of cross-ventilation and therapeutic differentiation43.

These examples reveal different approaches to the healthcare repurposing of convents: Milan, with the Senavra, anticipated a model centered on psychiatric specialization and suburban isolation; Mantua experimented with a more articulated internal distribution; Pavia opted for pragmatic, more adaptive solutions rather than design-driven ones. In all these cases, monastic enclosure – originally designed to preserve silence, contemplation, and order – proved surprisingly compatible with the needs of the new therapeutic paradigm, based on separation and classification of bodies44.

Yet it is particularly in the management of active marginality – vagabonds, beggars, and the unemployed – that the former convent reveals its full potential as a tool of governance: from a space of spiritual retreat to a disciplinary device oriented toward forced productivity. Within this logic, the transformation of suppressed religious complexes into poorhouses-laboratories and urban reformatories takes place45.

Alongside healthcare reform, the Habsburg government implemented a systematic policy to contain and reeducate vagrancy, viewed not merely as a social issue but as a moral and economic disorder46. Idleness, inactivity, and begging were no longer seen as exclusive objects of religious charity but as phenomena to be regulated through labor discipline. Within this framework, the transformation of convents into poorhouses-laboratories, reformatories, and prisons became part of a broader project of coercive welfare, inspired by a logic of forced social productivity. Convent structures, as architectural legacies of religious enclosure, were particularly well-suited for this purpose: based on a strict regulation of spaces and times, already predisposed to isolation, silence, and control, they were now “reactivated according to a new disciplinary logic47.

Unlike hospitals, where the focus was on care, these institutions aimed to induce behavior, instill order, monitor, and make industriousness visible. Convents offered infrastructure perfectly suited to this aim: cells, cloisters, refectories, and dormitories could easily be converted into collective dormitories, workshops, and wards divided by gender and function48.

Milan once again served as the experimental center for this policy49. As early as 1753, plans were discussed to build a large Poorhouse near Porta Nuova, conceived as an integrated structure combining a reformatory, prison, and manufacturing workshop (fig. 6) – though it was soon scaled back to a single wing designated as the House of Correction for budgetary reasons50. In 1766, thanks to a testamentary bequest from the noble Prince Antonio Tolomeo Trivulzio, the Pio Albergo Trivulzio was established, particularly intended for the care of the elderly. It became a model for other cities due to its “spacious, monumental, and well-designed premises”51.

At the same time, it became necessary to separate the House of Correction from the Penitentiary, built near Porta Vercellina, an area with numerous manufacturing industries. This structure, also based on prisoner labor, consisted of two large rooms of over 400 square meters each, designed more by a road engineer than an architect – a sign of the increasing importance of technical function over monumental form52. In 1777, to enhance its economic output, adjacent workshops were built and assigned to the inmates for artisanal production.

Nearby stood the already-mentioned former convent of San Vincenzo in Prato, previously used as an asylum. In 1784, highlighting the area’s productive vocation, the mentally ill were transferred to the Senavra, and the building was converted into a Voluntary Workhouse for individuals of both sexes. The project called for two separate wings for men and women, across two floors, each housing four large manufacturing spaces. This was the realization of the belief that “curing idleness” could only be achieved “through the promotion of industry and compulsory labor”53.

In Pavia, the high incidence of unproductive and destitute individuals had already prompted plans in the 1760s to build a Poorhouse. The project, inspired by both philanthropic and corrective ideals, called for a large complex between the gate toward Milan and the monastery of Sant’Epifanio. It was intended to house various categories of the poor – “ashamed poor,” infirm priests, orphans, and deviants – divided by type of assistance: support, training, or correction54. Alongside this, a civil and military academy was envisioned for the most capable individuals, with the goal of removing part of the marginalized population from idleness and unemployment55.

However, it was the convent complex of San Fedele, made available by the Josephine suppressions, that became the actual centerpiece of the new welfare reform project. In 1786, engineer Girolamo Pizzocaro was officially tasked with designing a Workhouse in accordance with the rationalizing principles of the Habsburg state. The former convent – spacious, centrally located, and already equipped with an autonomous and compartmentalized structure – was seen as an ideal site for this new institution56.

Leopold Pollack, building on his experience with Milan’s San Vincenzo Workhouse, also submitted a conversion project for the Pavia complex. However, his proposal failed to gain the support of Chancellor Kaunitz57.

Unlike other Lombard capitals, Mantua at the time had an extremely fragmented welfare system, with a multitude of small entities unevenly distributed across the urban fabric. Alongside the Ospedale Grande, the city’s main facility for the sick, operated many minor institutes dedicated to specific social categories: the Ospedale dei poveri orfani di Sant’Antonio, for abandoned children; the Company of the Holy Trinity, serving pilgrims and catechumens; and various female-run institutions such as the Pio Luogo della Misericordia, the Pio Luogo del Soccorso, and the Casa di Sant’Anna delle Derelitte, which served orphans, spinsters, mistreated, or abandoned women58.

For the homeless poor, a small overnight shelter was available at the Poorhouse. Despite the limited capacity and irregular distribution of these facilities – which compromised their effectiveness – the city lacked a unified and adequate welfare center59.

The differences between these three contexts reveal the flexibility of the Habsburg model. Milan developed centralized and specialized structures with a strong productive vocation; Pavia emphasized an educational, meritocratic, and selective function; Mantua, unlike the other capitals, did not build a centralized institution for assistance and reeducation, but instead made use of existing buildings.

The convent thus became a normative space for marginalized adults, where labor was a means of redemption and forced productivity60. But the same principle – order, discipline, control – was applied to a group even more central to the reform project: children. Indeed, it was with regard to orphaned or abandoned children that the claustrum in its secular form became a laboratory of civic training and moral shaping61.

In the social reform project promoted by the Habsburg monarchy, abandoned or orphaned children held a central position62. Poor children were now seen as potential human capital to be recovered, educated, and employed: assistance was no longer limited to feeding and sheltering, but needed to educate them in labor, discipline, and order. In this new vision, the orphan became a “child of the State,” and the desacralized convent – once dedicated to spiritual formation – was transformed into an educational and productive space.

With the 1772 decree, Maria Theresa officially assigned the care of orphans in each Lombard capital to the State, mandating the creation of public and centralized orphanages. Many of the resources freed up by the suppressions were redirected specifically for this purpose, launching a genuine building program for social care that involved the main cities of Lombardy63.

In Milan, the most emblematic project was the transformation of the Benedictine convent of San Pietro in Gessate into the new boys' orphanage. The task was entrusted to Giuseppe Piermarini, who undertook a radical yet respectful renovation of the original structure. The new complex was organized around two courtyards: one for rural activities, and the other for dormitories, the refectory, and workshops arranged on two levels. The spaces were designed to be not only functional and well-ventilated, but also to represent the rational and stable order of the State. The requirement to teach a trade to the orphans led to the creation of internal workshops (1777–1780), making the convent ideal in its new educational-work function (fig. 7)64.

The treatment reserved for orphan girls, however, was less innovative: the girls’ orphanage remained at its historic location in the Ospizio della Stella, which was smaller and less renovated. Only in 1784, following further suppressions, was the complex expanded to include the former convent of Santa Maria di Loreto (“Ochette”), intended to house girls with physical and mental disabilities65.

Unlike other Lombard cities, Mantua did not have a proper orphanage. Childcare, like poor relief, was provided by a patchwork of small, often female-run organizations located in cramped or poorly equipped facilities. The mandate to establish an orphanage thus opened up the possibility of experimenting with a unified model that would house both orphans and poor adults, based on a rationale of rationalized care and economic restraint (fig. 8). The project of a mixed orphanage was innovative for Mantua, but absorbed much of the available resources, delaying – or possibly discouraging – the creation of a Poorhouse66.

In Mantua, where no centralized structure for abandoned children yet existed, an attempt was made to concentrate both orphans and poor adults into one single complex. The general orphanage, housed in the former Augustinian convent of Sant’Agnese merged with the Pio Luogo del Soccorso, was initially assigned to Piermarini, then reassigned to chamber architect Paolo Pozzo67. The project envisioned a mixed institution, including dormitories, refectories, textile workshops, and separated areas for boys and girls.

The rising costs of renovations and the 1784 edict by Joseph II, which mandated strict gender separation and functional classification of care environments, led to the interruption of the project and its reconversion into a barracks. The boys were transferred to the former convent of Santa Lucia, the girls to Santa Maria Maddalena, adjacent to the Pio Luogo della Misericordia. The architectural intervention, by Pozzo and Pollack, followed the new hygienic-sanitary guidelines: well-ventilated spaces, infirmaries, bathrooms, and no superfluous decoration. The clean, regular articulation of the façades reflected the Enlightenment ideal of functional transparency and moral discipline68.

In Pavia, the conditions of the existing orphanages (San Siro for girls, San Majolo for boys) were so dire that a complete overhaul was necessary. After various proposals, it was decided to concentrate all children – both boys and girls – in the monastery of San Felice, renovated under the supervision of Pollack69. Here too, the monastic building offered a modular structure that could be easily adapted to new functions: cells became dormitories, cloisters turned into recreational courtyards, and refectories were repurposed as training classrooms.

What emerges from this comparison is a strong ideological consistency – labor, discipline, hygiene, differentiation – accompanied by operational differences tied to local resources, building quality, and the influence of key figures such as Piermarini or Pollack. If the orphan was now seen as human capital to be recovered, knowledge itself became political capital to be managed70. It was not just about providing care, but about forming useful, disciplined, and informed citizens. Hence the repurposing of convents into spaces for public education and the secular production of knowledge – the final outcome of the Enlightenment project to secularize the claustrum.

In the vast project of urban repurposing promoted by the Habsburg monarchy, education was one of the most strategic areas for building a new social order71. Education served not only cultural needs but also a clear logic of governance: to instruct meant to discipline, to produce useful knowledge, and to spread civic values. In this light, convents and monasteries also offered ideal spaces to house schools, academies, and universities: centrally located, solid, self-sufficient, and already designed for communal life72.

The case of Brera in Milan is emblematic. After the suppression of the Jesuit Order in 1773, the entire complex was designated to become a citadel of secular knowledge. In a 1774 decree, Maria Theresa ordered that “all revenues from the vacated Jesuit estate would be used for public education,” explicitly stating the will to convert ecclesiastical wealth into educational capital for the State73. The Jesuit college was repurposed as the Liceo di Brera, and later became home to the Academy of Fine Arts, the Astronomical Observatory, the Botanical Garden, the Braidense Library, and the School of Mechanics. The coexistence of these institutions under one roof reflected the new vision of integrated and public knowledge, in sharp contrast to the previous confessional model of teaching (fig. 9)74.

In Pavia, the reform of the university – launched in 1771 at the sovereign’s direct initiative and carried out under the direction of Carlo Firmian – was accompanied by a new geography of educational spaces75. Several religious buildings were converted to host scientific cabinets, classrooms, and anatomical theaters, libraries, and student colleges (fig. 10). A report from the Giunta Economale stated that buildings were evaluated “with attention to the good use that could be made of them for the public good, and in particular for the cultivation of sciences and the arts” (1772)76. These were not just available spaces: they were spaces already structured for discipline, concentration, and separation from urban disorder – and therefore ideal for the experimental and rational knowledge that the state sought to promote77.

In Mantua, the Palazzo dello Studio – formerly Jesuit – represents a successful example of adapting a pre-existing religious complex to the new educational model promoted by the Teresian school system78. The renovation works preserved the original layout of the religious complex but overlaid it with new functions aligned with the state’s secular education program, such as the Chemistry Laboratory and the Physics Cabinet. The project aimed to produce large, well-ventilated, healthy, and rigorous environments, in line with the imperial decree of 1784, which established minimum architectural standards for all schools and orphanages in Lombardy: “absence of ornamentation, regularity of openings, functional separation of spaces, and provision of bathrooms and infirmaries”79.

The transformations of Brera, Pavia, and Mantua therefore followed a shared logic: to reuse the physical shell of the sacred in order to establish a new architecture of public education. The convent – once a space of separation and silence – was not demolished but repurposed: from a place of spiritual salvation to an instrument for building the citizen80.

The 18th-century conversions of convents in Austrian Lombardy do not merely represent a trajectory of functional secularization. More profoundly, they demonstrate the surprising resilience of a spatial model born of exclusion and capable of surviving ideological change. The claustrum was not abolished, but reformulated: from sacred space to infrastructure of control, from a place of individual salvation to a collective mechanism of governance.

In each Lombard capital, the transformation followed different paths, adapting to specific institutional roles and urban-social structures. Milan, the administrative capital of the Kingdom, stood out for adopting a centralized and specialized model: the former convent of San Vincenzo in Prato was repurposed first as an asylum, then as a workhouse; Senavra became a modern psychiatric hospital; Brera was transformed into a citadel of secular knowledge. Here, enclosure was reconfigured as an instrument of medical, productive, and educational control, in line with a broader, well-planned urban governance project.

Pavia, a university city with an educational vocation, instead showed a more selective transformation focused on instruction: the former convent of San Fedele was designated for labor reeducation, while San Felice became a mixed orphanage. The emphasis here was on civic formation and the disciplining of bodies through education and merit. Enclosure survived as a device of concentration and moral profiling — aimed at forming citizens rather than supervising deviants.

Mantua, finally, a city with a weaker and more fragmented welfare infrastructure, adopted a mostly adaptive approach to reuse. The former Sant’Agnese was designated as a general orphanage, later reconverted into a barracks for economic reasons; other complexes were given multiple, compensatory functions. Rather than a systematic model, a pragmatic logic prevailed, where enclosure was reactivated as a building resource in a context of scarcity.

In all cases, the convent was not simply adapted: it was reinvented as a machine for care, containment, reeducation, or formation. Separation, silence, compartmentalization, and the rituality of time and gestures – foundational elements of religious enclosure – were reactivated through secular, medical, educational, or productive codes.

Modernity did not dissolve the claustrum: it translated it, institutionalized it, and made it appear neutral. The fortress of the sacred became a laboratory of utility, an instrument of good governance, a stage for the public good. Yet, in its walled geometries, its regulated rhythms, its orderly voids, it still speaks a language of separation. Enclosure, far from disappearing, has been transformed into a spatial grammar of power.

notes

Alberti, Leon Battista. 1989. L’Architettura. Translated by Giovanni Orlandi. Milan: Edizioni Il Polifilo.

Iliakis, Manolis. 2014. “Cloisters as a Place of Spiritual Awakening.” In Proceedings of the Architecture and Asceticism Conference. Durham: Durham University.

Spalová, Barbora, and Jan Tesárek. 2021. “Other Time: Construction of Temporality in Monasteries of Benedictine Tradition.” Time & Society 30, no. 2: 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X20953858. Repishti, Francesco. 2018. Architetture monastiche e spazio urbano. Milano: Scalpendi. Farina, Piero. 2009. Architettura conventuale tra Rinascimento e Riforma. Milano: Unicopli.

Evangelisti, Silvia. 2014. Monastic Poverty and Material Culture in Early Modern Italian Convents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

“Behind the Wall: Monastic Enclosure and the Practice of Separation.” 2013. Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures 39, no. 1: 60–65.

Cantale, Claudia, Tiziana Lombardi, and Simona Bodo. 2017. “The Shape of a Benedictine Monastery: The SaintGall Ontology.” Applied Ontology 12, no. 3-4: 321-340. https://doi.org/10.3233/AO-170191.

Foucault, Michel. 1984. “Space, Knowledge and Power.” Interview by Paul Rabinow. In The Foucault Reader, edited by Paul Rabinow, 239–256. New York: Pantheon.

Meriggi, Marco. 1983. Amministrazione e classi sociali nel Lombardo-Veneto. 1814–1848. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Beales, Derek. 2009. Joseph II: Against the Background of Enlightenment and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Venturi, Franco. 1979. Settecento riformatore. Da Muratori a Beccaria. Turin: Einaudi, 437–449.

Capra, Carlo. 2002. Il Ducato di Milano in età teresiana. Rome: Carocci. Bizzocchi, Roberto. 1985. “L’assolutismo illuminato e la Lombardia austriaca.” In Storia d’Italia, edited by Alberto Asor Rosa, vol. 5, 89–110. Turin: Einaudi.

Among the most impactful measures were the creation of the Ferma Generale for tax collection (1749–1751), the establishment of the Monte Santa Teresa for managing public debt (1753), and, above all, the completion of the new land register (1759), based on actual surveys rather than self-declarations.

Rao, Anna Maria. 1990. Riforme e consenso nel Settecento italiano. Rome: Laterza, 118–22.

Taccolini, Mario. 2000. Per il pubblico bene: la soppressione dei monasteri e conventi nella Lombardia austriaca del secondo Settecento. Rome: Bulzoni. Farina, Gianraimondo. 2011-2012. Aspetti e problemi finanziari in ordine alla soppressione di monasteri e conventi nella Lombardia asburgica del secondo Settecento: il Ducato di Milano. PhD diss., Università degli studi di Verona.

Galasso, Giuseppe. 2002. Alla periferia dell’Impero. Il Regno di Napoli nel Settecento. Florence: Le Monnier, 305–310.

Sperber, Jonathan. 2000. Revolution and the Transformation of European Societies, 1789–1848. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 44–45.

Buganza, Stefania. 2014. “I luoghi della clausura tra dismissione e rifunzionalizzazione: il caso lombardo.” Storia Urbana 145: 23–41. Farina, Gianraimondo. 2011-2012. Aspetti e problemi finanziari in ordine alla soppressione di monasteri e conventi nella Lombardia asburgica del secondo Settecento: il Ducato di Milano. PhD diss., Università degli studi di Verona.

Foucault, Michel. 1976. Sorvegliare e punire: Nascita della prigione. Translated by Piero Pasini. Turin: Einaudi, 226–245.

Ferraresi, Alessandra. 2001. Il tempo delle riforme: Stato e società nella Lombardia austriaca. Milan: FrancoAngeli, 35–38.

Rao, Anna Maria. 1990. Op. cit., 129–135.

Beales, Derek. 2009. Op. cit., 244–249.

Buganza, Stefania. 2014. Op. cit., 26–31.

Bizzocchi, Roberto. 1985. Op. cit., 101–105.

Venturi, Franco. 1979. Op. cit., 445–447.

Patetta, Luciano. 1992. “Soppressione di ordini religiosi e riuso civile dei beni in Lombardia.” In Veneto e Lombardia tra rivoluzione giacobina ed età napoleonica. Economia, territorio, istituzioni, edited by Antonio Lazzarini and Giovanni Luigi Fontana, 391–394. Milan: Cariplo-Laterza. Meriggi, Marco. 1983. Op. cit., 23–25.

Salsi, Claudio. 2000. “Da Santa Maria della Scala al Teatro alla Scala: la trasformazione urbana come politica culturale.” In Milano e l’età dei lumi, edited by Sergio Rebora, 91–105. Milan: Skira.

Seidel Menchi, Silvana. 1991. “Università e riforme nell’Italia del Settecento.” In L’università e le città, edited by Dino Puncuh, 205–223. Florence: Olschki.

Rossi, Ginevra. 2022-2023. Mantova nel Settecento: assistenza, istruzione e sanità. Il patrimonio camerale nei progetti dell’architetto Paolo Pozzo. PhD diss., Politecnico di Milano.

Mostaccio, Silvia. 2017. I gesuiti e le soppressioni nell’età moderna. Rome: Carocci, 144–150.

Sperber, Jonathan. 2000. Op. cit., 50–55.

Taccolini, Giuseppe. 1989. Finanza e assistenza nella Lombardia austriaca. Brescia: Morcelliana.

Foucault, Michel. 1976. Op. cit., 228–230.

Buganza, Stefania. 2014. Op. cit., 29–35.

Archivio di Stato di Milano (ASM). The numerous reports produced by the Economic Council (Giunta Economale) are preserved at the State Archives of Milan (ASM) in the 'Culto, parte antica' collection. Cfr. Taccolini, Mario. 2000. Op. cit., 19-62.

Ferraresi, Alessandra. 2001. Op. cit., 112–115.

Malamani, Anita. 1982. “L’organizzazione sanitaria nella Lombardia austriaca.” In Economia, istituzioni, cultura in Lombardia nell’età di Maria Teresa, vol. III, edited by Aldo De Maddalena, Ettore Rotelli, and Gennaro Barbarisi, 991–1010. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino.

Foucault, Michel. 1963. Naissance de la clinique. Paris: PUF. Italian translation: Nascita della clinica. Translated by Alessandro Fontana. Turin: Einaudi, 1976, 97–105.

Dezzi Bardeschi, Marco. 1991. Architettura e utopia terapeutica. Ospedali e manicomi nella modernità. Milan: Electa, 24–29.

Panzeri, Laura. 1993. "La Senavra: un ospizio per i folli nel quadro della riforma delle strutture assistenziali a Milano." In Dalla carità all’assistenza. Orfani, vecchi e poveri a Milano tra Settecento e Ottocento, edited by Cristina Cenedella, 164-169. Milano: Electa.

Seidel Menchi, Silvana. 1998. “Repressione e assistenza nella Lombardia tardo-settecentesca.” In Luoghi della carità e della disciplina, edited by Lucia Sandri, 231–237. Florence: Olschki. Scotti, Aurora. 1984. Lo Stato e la città. Architetture, istituzioni e funzionari nella Lombardia illuminista. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

Fontana, Anna Chiara. 2004. “Faustino Rodi e la riforma degli ospedali a Cremona.” Annali di architettura 16: 79–88. Tassini, Sonia, and Mariella Morandi. 1989. “Faustino Rodi: un architetto neoclassico nella Cremona del XVIII–XIX secolo: saggio di esplorazione.” Arte Lombarda 90/91: 162–177.

Dardanello, Giuseppe. 2010. “L’Ospedale di Mantova tra assistenza e architettura.” In Spazi di cura nel Settecento lombardo, edited by Stefania Buganza, 91–103. Mantova: Edizioni Tre Lune.

Ballabeni, Francesca. 1995. “Le vicende e le fabbriche dell’ospedale mantovano nel quadro delle riforme asburgiche.” Postumia 6: 89–98.

Sperber, Jonathan. 2000. Op. cit., 57–59.

Foucault, Michel. 1976. Op. cit., 231–234.

Foucault, Michel. 1976. Op. cit., 219–225.

Ibid.

Riboli, Ivanoe. 1993. “La Casa di Lavoro Volontario a Milano e la Pia Casa ad Abbiategrasso.” In Dalla carità all’assistenza. Orfani, vecchi e poveri a Milano tra Settecento e Ottocento, edited by Cristina Cenedella, 157–63. Milan: Electa. Meriggi, Marco. 1983. Op. cit., 39–42. Mazzucchelli, Vincenzo. 1982. “Il ‘bene della società civile’. Riforme e povertà nella Milano della ‘benefica sovrana’.” In Economia, istituzioni, cultura in Lombardia nell’età di Maria Teresa, vol. III, edited by Aldo De Maddalena, Ettore Rotelli, and Gennaro Barbarisi, 161–240. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino.

Ferraresi, Alessandra. 2001. Op. cit., 118–123.

The project, drafted by Giuseppe Merlo, Giulio Galliori, and Francesco Croce, envisioned a cellular layout with separate wings for men and women, and a central lavoriero—a grand space for collective production. However, due to its monumental scale, the plan was scaled down, and more modular solutions were adopted. Ferri, Gabriella. 1982. “La riforma della pubblica assistenza sotto il governo di Maria Teresa: l’architetto Francesco Croce e la costruzione dell’Albergo dei Poveri della città di Milano.” In Timore e carità. I poveri nell’Italia moderna, edited by Giorgio Politi, Mario Rosa, and Franco Della Peruta, 225–235. Cremona: Annali della Biblioteca Statale e Libreria Civica di Cremona.

Buganza, Stefania. 2010. “Dalla clausura al controllo: conventi lombardi e riforme teresiane.” In Spazi di cura nel Settecento lombardo, edited by Stefania Buganza, 141–147. Mantova: Tre Lune. Madoi, Roberta. 1990. “La crescita del Pio Albergo Trivulzio di Milano illustrata dai disegni del suo archivio.” Il disegno di architettura 2: 78–80.

Fontana, Anna Chiara. 2012. “Architettura della punizione: la Casa di Correzione e l’Ergastolo a Milano nel XVIII secolo.” Storia Urbana 137: 89–105.

Della Peruta, Franco. 1987. Milano: lavoro e fabbrica. 1814–1915. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

Seidel Menchi, Silvana. 1998. “Poveri, mendicanti e devianti nella Lombardia riformata.” In Luoghi della carità e della disciplina, edited by Lucia Sandri, 223–229. Florence: Olschki.

Maggi, Laura. 1980. “Verso una gestione laica dell’assistenza: dai progetti per le ‘case di lavoro’ agli edifici per la cura e l’educazione degli orfani.” Annali di Storia pavese 2–3: 181–192.

Capra, Carlo. 1987. La Lombardia austriaca: istituzioni, economia, società. Bologna: Il Mulino, 252–255.

Scotti Tosini, Aurora. 1984. Architettura austriaca in Lombardia: il classicismo di Leopold Pollack. Milan: Electa, 84–89. Maggi, Laura. 1979. “Gli edifici pubblici promossi da Giuseppe II a Pavia. L’attività di Leopoldo Pollach.” Bollettino della Società pavese di storia patria 31: 96–118.

Grechi, Giovanni. 2006. “Le istituzioni assistenziali femminili nella Mantova del Settecento.” Annali di storia mantovana 17: 59–72.

Dardanello, Giuseppe. 2010. “L’assistenza pubblica a Mantova nel XVIII secolo.” In Spazi di cura nel Settecento lombardo, edited by Stefania Buganza, 173–178. Mantova: Tre Lune.

Sperber, Jonathan. 2000. Op. cit., 67–72.

Foucault, Michel. 1999. Les Anormaux: Cours au Collège de France (1974–1975). Paris: Seuil/Gallimard. Italian translation: Gli anormali. Milan: Feltrinelli, 2000, 101–107.

Beales, Derek. 2009. Op. cit., 243–248. Maggi, Laura. 1982. “La riforma delle infrastrutture urbane in età teresiano-giuseppina: le fabbriche degli orfanotrofi lombardi.” Storia della città. Rivista internazionale di storia urbana e territoriale 22: 49–64.

Buganza, Stefania. 2010. “Orfani, conventi e riforme: la costruzione del nuovo orfanotrofio milanese.” In Spazi di cura nel Settecento lombardo, edited by Stefania Buganza, 111–125. Mantova: Tre Lune. Maggi, Laura. 1982. “La riforma delle infrastrutture urbane in età teresiano-giuseppina: le fabbriche degli orfanotrofi lombardi.” Storia della città. Rivista internazionale di storia urbana e territoriale 22: 49–64.

Dodi, Luisa. 1993. “L'Orfanotrofio dei Martinitt nell'età delle riforme.” In Dalla carità all’assistenza. Orfani, vecchi e poveri a Milano tra Settecento e Ottocento, edited by Cristina Cenedella, 127–146. Milan: Electa.

Ibid.

ASM, Luoghi Pii, parte antica, b. 238 Il Nuovo piano per l’Orfanotrofio Generale di Mantova…, 26 gennaio 1775. Rossi, Ginevra. 2022-2023. Op. cit.

Dardanello, Giuseppe. 1998. “L’assistenza all’infanzia a Mantova: frammentazione e tentativi di centralizzazione.” In Luoghi della carità e della disciplina, edited by Lucia Sandri, 189–195. Florence: Olschki.

Scotti Tosini, Aurora. 1984. Architettura austriaca in Lombardia: il classicismo di Leopold Pollack. Milan: Electa, 91–96. Tolomelli, Davide. 2009. “Giuseppe Piermarini, Leopoldo Pollack e l’orfanotrofio maschile di Milano (1768–1810).” In Leopold Pollack e la sua famiglia. Cantiere, formazione e professione tra Austria, Italia e Ungheria, edited by Giuliana Ricci and Giovanna D’Amia, 83–91. Cesano Maderno: ISAL.

Fontana, Anna Chiara. 2013. “Igiene e sorveglianza nell’architettura assistenziale mantovana del tardo Settecento.” Storia Urbana 140: 133–46. Seidel Menchi, Silvana. 2007. “Educare e sorvegliare: l’orfanotrofio di San Felice a Pavia.” Annali di storia pavese 18: 77–84. Maggi, Laura. 1979. “Gli edifici pubblici promossi da Giuseppe II a Pavia. L’attività di Leopoldo Pollach.” Bollettino della Società pavese di storia patria 31: 96–118.

Foucault, Michel. 1999. Op. cit., 132–137.

Venturi, Franco. 1979. Op. cit., 460–467.

Foucault, Michel. 1976. Op. cit., 226–231.

ASM, Studi, p.a., b. 128, Imperial dispatch of February 12, 1774.

Buganza, Stefania. 2010. “L’Accademia di Brera come dispositivo urbano e culturale.” In Spazi di cura nel Settecento lombardo, edited by Stefania Buganza, 129–135. Mantova: Tre Lune. Ganna, Angela, and Marina Pisaroni. 1998. “Disegni di Piermarini per la riforma di Brera.” Arte Lombarda 122: 67–77. Scotti, Aurora. 1979. Brera 1776–1815: nascita e sviluppo di una istituzione culturale milanese. Quaderni di Brera 5. Florence: Centro Di.

Seidel Menchi, Silvana. 1991. Op. cit., 215–223.

ASM, Luoghi Pii, p.a., b. 238, January 21, 1775.

Rao, Anna Maria. 1990. Op. cit., 130–132.

Ceriani, Paolo, Federica Nicoli, and Katia Tamassia, eds. 2022. Un polo culturale nel cuore della città antica: il Palazzo degli Studi Liceo Virgilio di Mantova. Mantova: Publi Paolini. Grechi, Giovanni. 2008. “Il Palazzo dello Studio a Mantova: da collegio gesuitico a scuola pubblica.” Annali di storia mantovana 19: 113–21.

ASM, Luoghi Pii, p.a., b. 244, August 30, 1787.

Foucault, Michel. 1999. Les Anormaux: Cours au Collège de France (1974–1975). Paris: Seuil/Gallimard. Italian translation: Gli anormali. Milan: Feltrinelli, 2000, 142–145.

Tara Bissett

Edited by: Elisa Boeri (Politecnico di Milano), Luca Cardani (Politecnico di Milano) and Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano)

Eduardo Mantoan Paulo H. Soares de Oliveira Jr.

Giorgia Strano