In examining the construction of the prison, seminal studies have shown that prisons have become integrated into a broader, all-encompassing carceral system in modern society. This understanding of the prison beyond its confines has also drawn attention to the spatial extension of seclusion. The recognition of a prison’s liminal spaces, porous walls, and permeable boundaries calls for the disclosure of hidden spatial dynamics – bringing architecture to the forefront of the discussion. In this regard, this paper will advance two key arguments. First, by focusing on Kosovo within the complex historical landscape of former Yugoslavia, it will unravel how confinement transcends physical boundaries. To achieve this, the paper will draw on sources such as prison letters, poems, and testimonies – expanding the scope of evidence within architectural history. Second, by producing and utilizing architectural documents, it will develop a novel methodological framework to disclose spatial (dis)connections and their formative context.

To explore the shifting borders of confinement, this paper studies an inconspicuous building in Gjilan, Kosovo, which was one of the most notorious prisons of former Yugoslavia. Here, political prisoners were detained throughout the 1980s and 1990s, subjected to decades of torture and torment in inhumane conditions. The narratives of its survivors, distilled from testimonies, prison letters, and walk-along interviews, are closely tied to the prison’s spatial components (doors, windows, walls, corridors) and its surroundings (streets, adjacent buildings, public spaces). By focusing on these spatial elements, this paper will unravel how confinement can challenge and resist physical borders. It will explore not only material ways, such as prison visits and supplies, but also immaterial ones. These include the transmission of ideas through prison literature, the sense of confinement outside the prison due to surveillance, persecution, and letter censorship, as well as enduring traumatic memories.

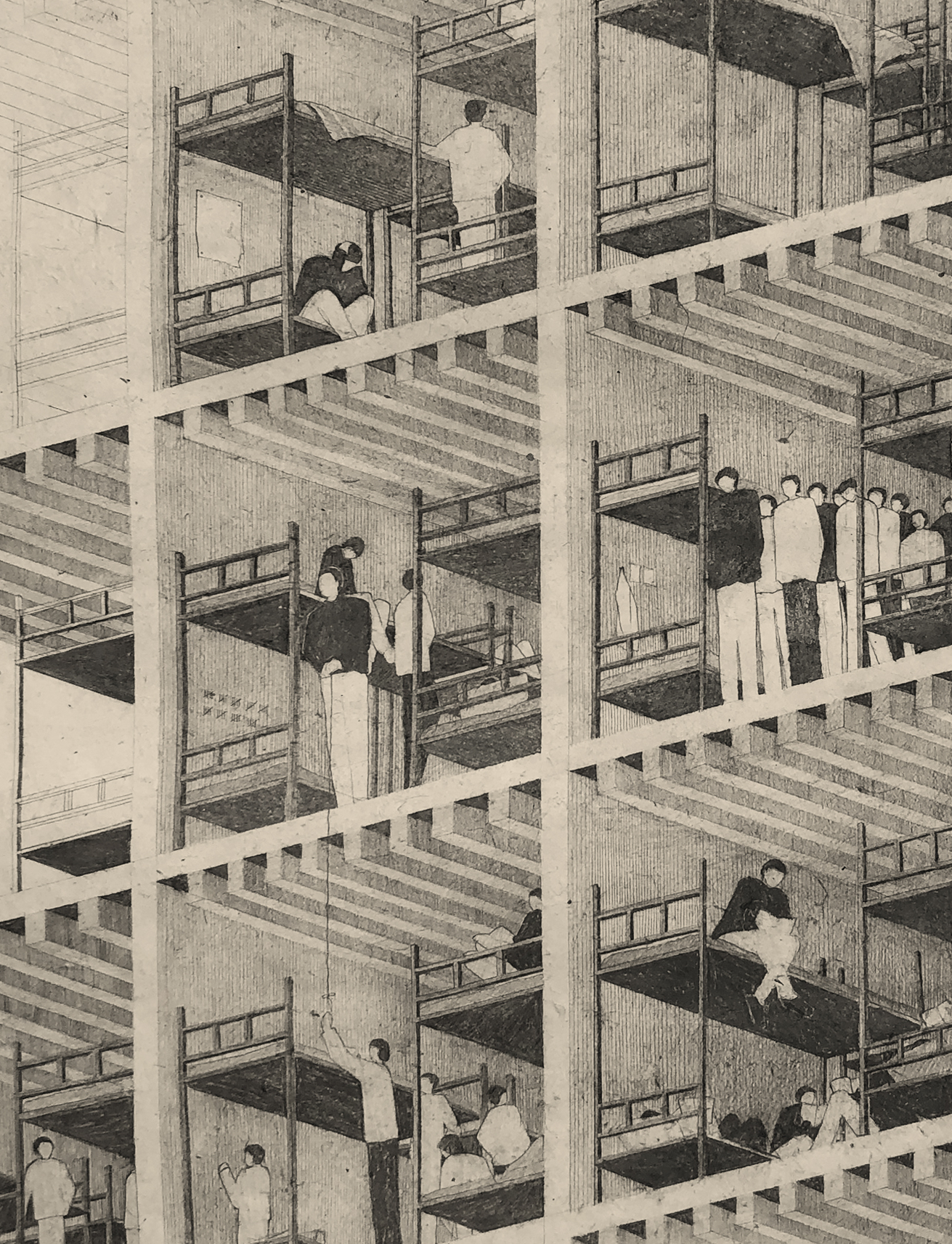

To disclose these spatial connections, this paper will rely on the production of maps, plans, sections, and models. Rather than serving as mere representations, these architectural artefacts function as active research tools, each offering a distinct lens. Maps help us reveal broader spatial connections, plans allow us to trace the internal organization of buildings, sections expose hidden vertical relationships, and finally, models bring structures into three-dimensional forms, making spatial dynamics even more palpable. The novelty of this approach lies precisely in the active and heuristic use of architectural artefacts in the disclosure of hidden spatial dynamics. In doing so, it extends beyond conventional architectural studies of prisons, which often focus on stylistic or typological analyses, renowned architects, psychological studies on confinement, or criminal justice studies on large political contexts.

The Prison of Gjilan, one of the most notorious prisons of former Yugoslavia, today stands abandoned and decaying in the center of Gjilan in Kosovo. Between 1980 and 1999, a period marked by the violent suppression of Kosovo Albanians by Yugoslav and later Serbian authorities, numerous political prisoners were tortured and tormented in inhumane conditions1. Despite its historical significance, the prison remains largely absent from architectural records, with no surviving blueprints or any official documentation. Lacking the hallmarks of a renowned architect or any notable stylistic values, the building has also been dismissed as architecturally insignificant. How, then, can we study a building that resists conventional approaches to architectural history? It is precisely through this question that the prison of Gjilan engages with two ongoing debates in architectural history: the question of architectural evidence and the status of the drawing.

While architectural history has long relied on coherent evidence such as buildings or their protagonist architects, more recent studies have highlighted the limitations of such monographic narrative forms. As a result, there has been a significant shift towards a broader understanding of evidence, which opened the field to more non-traditional sources: from administrative standards of technical and urban infrastructures, to bodily experience and oral history2. Building on this expanded view of evidence, this paper will turn to prison literature and oral history to reconstruct the spatial conditions of confinement. On the other hand, the status of the architectural drawing has long been attributed to its executional and representative functions. However, a shift in such understandings emerged in the mid-20th century with new discussions on the drawing’s instrumentality and agency. This agency has been thoroughly examined by Robin Evans, who notes that

[...] the properties of drawing — its peculiar powers in relation to its putative subject, the building – are hardly recognized at all3.

While Evans does disclose the generative power of drawings, it still remains very much linked to their executive role in the translation from drawing to building. Here, what I believe to be another largely unrecognized generative power, exists just as much in the opposite direction — drawing post-production. The act of drawing existing structures — be it through maps, plans, sections or models — can help reveal certain spatial aspects that remain inaccessible through other means.

Addressing the challenge of piecing together fragmented narratives and dispersed architectural evidence, this paper will employ a dual theoretical framework: Carceral Geography and Narrative Theory. Carceral Geography provides a lens through which to examine the prison as a particular spatial condition4. While it covers a wide range of perspectives from cultural to political approaches, the focus of this paper will lie on exploring the prison boundary and its in-between spaces. As studies have already recognized the prison’s liminal spaces, porous walls, and blurred boundaries, the paper’s contribution to this discourse will focus specifically on the role of architectural documents in disclosing overlooked connections. Narrative Theory, in turn, offers a view on narratives not as mere reflections of human experience, but as active instruments for deciphering spatial dynamics5. In this paper, its role is twofold. On the one hand, it helps examine what we can spatially infer from existing narratives. On the other hand, it offers storytelling as a means for reframing existing narratives, in order to reveal and make evident hidden spatial dynamics.

The paper opens with a newly constructed narrative that emphasizes the shifting borders of confinement in the prison of Gjilan. What it evokes, however, is not a linear sequence of events that happened as such in reality6. Rather, it employs a fictional framework that brings dispersed traces of different narratives into one linear space. More precisely, the story will trace the movement of one sound in prison — from its origin in the city, entering the prison cell, finding place in the poem, going through layers of control and surveillance, returning to the city, and finally, reaching you, the reader. Although this chapter takes a literary form, it is by no means a diary entry or an idiosyncratic exercise. Rather, it is a literary tool through which dispersed traces of undisclosed spatial connections come together and become apparent to the reader. The following chapter then returns to the original narratives of former political prisoners, further exploring the link between lived experience and space. Finally, the paper discloses the starting point of this overall investigation: the production of architectural artefacts. It is here, in the act of making, that the first spatial revelations emerge.

The paper is structured in such a way that, from the first chapter, it engages the reader directly with the research findings. However, it is important to note that although this spatial disclosure — namely, the shifting borders of confinement — becomes immediately apparent to the reader, it in fact emerged only later in the research process. In other words, the methodology behind this paper did not follow a linear process7. Rather, it operated through a feedback loop between the production of architectural artefacts, literary sources, and oral history. In the case of the Prison of Gjilan, the initial inquiry began with the production of drawings and models, which, as explained above, served as active tools in the disclosure of hidden histories. Although the decision to draw and make models started solely as a response to unavailable archival material, new questions emerged in this very act of making8. These were further informed by literary sources such as prison letters and poems, which deepened the spatial interpretation of the prison. Further, walk-along and semi-structured interviews brought new insights that, in turn, redirected attention back to the literary material and the act of making — creating a continuous loop of discovery. This process developed in multiple layers. At times, interviews reinterpreted or challenged insights drawn from literary sources; at other times, unexpected lines of discussion were opened by using the drawings and models during interviews. Therefore, as there are several research phases integrated into this feedback loop, the methodology cannot be reduced to a fixed or linear template. What appears as a clear narrative to the reader, then, is the outcome of a recursive and exploratory methodology.

It is spring of 1981. Streets all over Kosovo are bustling with student protests, and so is the boulevard spanning the north-south axis of Gjilan. Banners demanding freedom and independence for Kosovo Albanians ripple above the crowds, in defiance against the decades-long accumulation of oppression and injustice. On the same streets, the Yugoslav state security service (UDBA) advances with wagons, military tanks, tear gas and police batons striking against the unarmed. For the next two decades, the same streets will remain sites for chaos and resistance, inflicting a big shift in the city's configuration. Houses will become sanctuaries for underground movements, while prisons will fill with those who will later shoulder the historical responsibility of bringing freedom to their people.

At the main crossroad in the center of Gjilan, slightly behind the city hall, stands a T-shaped blue prison. Though not immediately visible from the main road, it is locked by the court and police station with their facades touching as if their functions are inherently inseparable. The only subtle hint showing the boundary between the two is a line formed from the two colored facades — blue for the prison and white for the court. The prison’s rear facade is the only hint one could get from the main road — a blue wall standing perpendicular to the street, parallel to the theatre building just twenty meters away. The theatre, less monumental than one might expect, extends to the city library in the back. Naturally, facing a theatre and a library, this side of the prison offers a little more than the opposite one enclosed in the police station’s courtyard. Perhaps for that reason it is there where the guards’ offices are located, often basking in the sunlight streaming through large square windows. Below them, three windows about one-ninth their size break the facade to open into three solitary cells. Double-barred and fully covered in tin, these windows offer no view of the theatre. If not the view, could the theatre’s sounds have found their way inside the cells?

If the theatre’s sounds do reach the prison cells, like the chirping of birds and growling of dogs, they are merely a part of a larger soundscape that penetrates the prison. While some sounds bring fragmented realities from the outside world, an entirely different rhythm occurs inside the prison. Guards shut the steel doors with force to jolt prisoners into constant wakefulness, while their movement is mapped continuously through the jingling of keys along the corridor. At the far end of the same corridor, the bathroom stands in front of the last prison cell. In cruel amusement, the guards control the water temperature from the outside, as the prisoners’ screams travel to the cells in front. Further down, at the end of the bottom T-wing, lie the interrogation rooms. The guards leave the windows open on purpose, ensuring that every scream travels across the courtyard and slips through the barred windows of those awaiting their turn.

Now, it is raining. For an hour or so, drops of rain cascade down the slanted tiles of houses across Gjilan. It washes over the former textile manufacturers and tobacco warehouses, and seeps through the elongated agricultural parcels along the city’s constrained topography. Rain also hits the prison. Here, it produces a sound different from that of ordinary houses. Going through layers of barbed wire coils, it threads through their spirals before striking the facade. It cannot touch the window itself, for in front of it stands a tilted tin sheet spanning its entire length. As soon as it meets the tin sheet, each drop strikes in an amplified sharpness to produce a piercing uneven rhythm. On this day, the sound of rain enters A’s poem:

In room thirteen,

colour grey

upon my wounds

The rain of day thirteen

on the window tin,

bullet on my dreamsWith thirteen other travellers

we go around the circles of hell,

to meet Galileo,

on day fourteen9.

Once the rain enters the poem, written in the thin skin of an old cigarette box, it waits folded and hidden. With eyes and barriers on all sides, its only opportunity to move seems to be the window — that same window, surrounded in steel bars and covered in tin, which keeps every beam of light from entering the cell. This time, the tin becomes a shield, guarding from the eyes of those who watch from the outside. Pulling a thread from his shirt, A twists it and ties it around the small cigarette paper scroll. As soon as it gets dark outside, he lifts the thread to the window, in between the bars, and lowers it through the narrow gap. The small piece of paper carrying the sound of rain touches the facade softly until it reaches the window below. Inside this cell, B waits, not for the sound of footsteps or the turn of a key, but for the fragile scratch of a paper descending until it reaches his window sill. The sound of rain has arrived on the first floor.

On the first floor, B traces the delicate folds of the paper and presses it flat on his palm. The poem cannot stay, it must keep moving to resist detection. In the other cell, there is X, a half-paralyzed political prisoner who is serving a sentence for driving with a banner that wrote Kosova Republikë. X, having two more months before the end of his sentence, asks B to write the poem on the smallest piece of paper possible. “I’ll get them out,” he tells B, in a calm and determined tone. B hesitates, knowing the inhumane consequences that would await him in case of discovery. Insistingly, X gets hold of the poem, cuts the rubber of his wheelchair, and tucks the piece of paper inside the punctured inner tube. He seals it back up with glue and continues moving on his wheelchair as the poem makes circles front and back.

As the wheels turn, the sound of rain circles with them. For most of its time, the paper stands still in the cell, but sometimes, it visits the corridors along which everyone paces with measured steps. On those rare occasions when X gets closer to the inspection room, he grips the wheels a little tighter. He knows all too well what happens behind that door — letters are torn, books shaken, and even food is turned inside out under the sharp tip of the guard’s copper spear. It is that door, the border of which most items can never cross. Yet, in all their scrutiny, the guards are not interested in the poor man’s wheels. So, as X moves forward, rain rolls past the inspection room time and time again. On his last day, X passes through the gates and approaches the main exit. The sound of rain circles one last time in the dark narrow corridors, before it rattles over the uneven roads of Gjilan. It moves past the boulevard and the theatre, onto muddy villages, slipping out of the wheel to reach the hands of B’s waiting family. From there, it journeys on for 45 years, to safely reach you today.

In a letter written to his father in 1987, Merxhan Avdyli describes his morning routine of waking up before other prisoners, as the only time of day when one can hear “the chirping of jackdaws, the cawing of crows and ravens, as well as the singing of the thrushes”10. Teuta Hadri, imprisoned in 1981, recalls the four iron doors one had to pass to arrive at the women’s pavilion in Mitrovica, and its corridors mapped mentally by the sound of jingling keys in dreadful silence. “Back then, I said, I will never keep keys in my life,” she says, as she takes out her keys to let us inside her home for the interview to take place11. On a stroll around the abandoned prison of Gjilan in 2024, Ahmet Isufi points to the torture rooms in front of the prison, his finger tracing the route in the air where screams echoed from one facade to another. As we enter inside, Selajdin Abdullahu shuts the steel door with a heavy thud, reenacting the sound the guards used to traumatize the prisoners. It is through these and many other narratives of those involved in underground political movements in Kosovo, that the short story of How Rain Escaped Prison is framed to make visible the spatial dimension of traumatic experiences of political prisoners12.

These narratives, in their context, are first and foremost told to document a lived reality which points to a broader historical context — that in which Albanians of Kosovo lived within Yugoslavia. And it seems that, to convey the true essence of these stories, it would be more appropriate to speak in the form of information or report. But for that, Noel Malcolm argues that

to produce an adequate survey of the human right abuses suffered by the Albanians of Kosovo since 1990 would require several long chapters in itself13.

While the role of information remains essential, this paper focuses on another integral element of these narratives: the spatial experience. What storytelling conveys that information and reports cannot, is a transmission of experience that evokes in the reader a different form of understanding. In his short essay “The Storyteller”, Walter Benjamin points out that it is when the psychological connection of events is not forced on the reader and it is left up to him to interpret things, that “the narrative reaches an amplitude that information lacks”14. This approach, especially in a context in which storytelling does not happen for the sake of storytelling, can offer new spatial understandings beyond individual experience.

But why construct a new narrative? Why not insert these collected narratives as they are and discuss them in detail? To avoid an overwhelming description of traumatic accounts, this re-framing instead brings the focus on a widely overlooked dimension — the spatial component of traumatic memories. In each letter, poem, book, or interview, elements of movement, presence, and absence continually construct spatial memory. In her interview, Teuta Hadri speaks of mapping the guards’ movements in the prison of Mitrovica, not by sight, but through traces of light. On sunny days, as the guards would move silently along the corridor, their shadows would slip under her cell door15. However, for Ramadan Dermaku in the prison of Gjilan, no shadows appeared, as the corridors had no windows facing outside. For him, tracing their movement relied instead on sound: the guards’ footsteps and the jingling of keys16. This indirect understanding of space through daily accounts is not only present in practices of surveillance and torture, but also in the prisoners’ resistance to confinement. While some speak of secret practices of communication by knocking on walls, others recount how windows were utilized to send secret messages across different floors.

Some narratives extend even further, mapping spaces beyond the prison’s physical perimeter. While prisoners found ways to subvert the internal borders of the prison, the outer perimeter remained the most difficult of all. Every object that came in or out was subjected to severe censorship. Kosumi’s 1985 poem, Package Inspection, very well captures this invasive scrutiny. He describes how the most ordinary items — fruit, fli, and the mother’s halva — were stabbed by the guard’s copper spear, as if distrust extended not only to the prisoners but to nature itself17. The outer perimeter, however, was still somehow challenged. Xhavit Nuhiu smuggled poetry out of prison by concealing a small piece of paper inside the punctured inner tube of his wheelchair tire. As he sealed the tire back with glue, he carried the letter inside for over a month – risking severe punishment had it been discovered18. In another instance, Hysen Gega, another political activist, concealed written messages inside a bar of soap. Using a sharpened spoon handle, he hollowed out a space just large enough to fit a tightly wound roll of paper, then sealed the cavity with the same soap shavings, smoothing its surface to appear untouched19. The soap travelled undetected, and the poem got out.

The reach of confinement beyond the prison border did not only manifest in material ways, but also in immaterial ones. In Correspondence in Censorship, Mehmet Hajrizi speaks of his wife and children who used to travel for three days for a three-minute visit in the prison of Novi Sad, during which they were forced to sit 10 meters apart. Since these visits were rare, their primary means of communication became letters. Hajrizi explains that, though at home, his family lived under the constant weight of surveillance and silencing, as letters went through multiple layers of censorship from prison authorities, secret services and the judicial system20. Bajram Kosumi’s imagery, too, speaks to this pervasive sense of control, as he describes the

heavy black stamp – and not that solemn kind of black — pressed over the written text like a palimpsest, bearing the word "cenzurisano", [which] evokes the image of a death telegram or violence inflicted upon the text21.

This layered censorship became often embedded into the act of writing itself, leading to self-censorship for both those in prison and at home. In a letter to his daughter in January 1987, Ahmet Qeriqi writes, “I am writing to you without any hope that you will receive this letter, as it seems that letters written in Albanian are not allowed here, even though they do not say it openly.” Three months later, he writes again: “Be careful, my dear daughter, to write without making illustrations or drawings, just as I have written this letter to you”22. What becomes clear through these accounts, is that the practice of censorship was not limited to the inspection room, nor to the prison building or its surroundings, but stretched far further to reach those who lived “freely”.

Turning the prisoners’ narratives into a linear spatial story does not follow an arbitrary route. What precedes the narratives’ analyses, in fact, is the drawing of the prison itself. With unavailable archival sources, drawing becomes not only the first tool with which to approach the building, but also the instigator leading to all research outcomes. Rather than serving the purpose of precise documentation, it takes on different roles, as a research tool and a mediator. The first one in a series of many is a floor-plan drawing (fig. 1). Initially, it discloses visible spatial hierarchies: the guards’ offices larger than the cells, with far more light and broader views; the unaligned doors along the corridor, keeping prisoners from seeing the guards’ rooms; the systematic repetition of doors, reinforcing in prisoners a sense of disorientation and confinement — and so on. Yet, besides exposing spatial relations in the prison’s design, the drawing raises fundamental questions of architectural representation. How does one draw a prison door? Can you draw a door that is almost more of a wall than the wall itself, in the same way as a conventional door?

The same drawing defines the borders of the prison: the building ends there, the courtyard is enclosed, and the outer perimeter is fixed. ‘That’ is the prison. Yet, the floor plan drawing strains against these limits once sound comes into question. Following, the soundscape drawing (fig. 2) expands to trace a larger environment of life in prison. It begins with the inside, tracing the clang of steel doors, the jingling of keys and the pounding of rain against tin-covered windows. It then moves slightly outward, capturing shuffled voices from the courtyard and screams traveling from windows of one facade to another. It is only later, that poems, letters and conversations with former prisoners reveal sounds from beyond the prison’s perimeter. On a walk behind the prison, Isufi speaks of the solitary cells while pointing at their windows touching the ground. Suddenly, he turns around to point at the rear part of the theatre. “That was the city library,” he says, “I used to read there a lot as a child.” In that moment, the drawing faced a new question: given the proximity, could faint melodies from the theatre have drifted into the cells? How far must the drawing stretch to capture not only what we see of the prison, but also what is seen, heard, and remembered from within it?

What follows is a section drawing (fig. 3), which opens a previously unseen dimension — the vertical cut. This vertical section reveals relationships that cannot be observed in a site visit, nor in horizontal projections such as floor plans. It first traces the cells’ proportions, concrete ceiling bars, sight lines, and bunk beds. When perspective is added to the drawing, narratives begin to unfold inside each room. Some show the overcrowded cells with up to thirteen prisoners in one room, while others reveal prisoners reading on their bunk beds or standing in place and facing the window23. As pencil shades darken each cell of the section, the structure of the prison remains blank – its walls and slabs forming a white grid. Here, then, the boundaries become clear — thick, heavy walls and concrete slabs separating each narrative as they unfold independently within their small box. Yet, in certain narratives, the pencil traces over the white grid. Abdullahu recalls how coded knocks on the wall allowed prisoners to communicate between cells, a rhythm of taps signalling messages such as the arrival of a new cellmate24. In this instance, the wall transforms from a rigid border into a conduit of communication. Similarly, Isufi shares another story: taking a piece of paper from a cigarette box, writing on it, and then tying it with a thread from his shirt to lower it out of the window to the cell below25. It is here, that the section starts to expose connections between adjacent cells, or even those across different floors – challenging the idea of a total, isolated prison cell.

Moving from architectural drawing to model-making, the next artifact introduces a 1:10 section model, bringing the prison cell into three-dimensional form (fig. 4). Unlike drawings, the model engages more directly with proportion, light, texture, and detail. For instance, the choice of white cardboard as material plays a crucial role in the model’s perception. Stripped of its patina of decay, the cell is abstracted into an unsettling, pure white space. But beyond materiality and perception, there is something in the very act of making that is of the essence here. As the window is built, the thickness of the wall becomes evident, with an immense depth and covered by bars on both sides. The tilted tin sheet — a detail encountered repeatedly in the prisoners’ accounts — is now fixed in place, enclosing the window completely. As this element takes shape in the model, it begins to resist previous narratives: how did Isufi manage to slip a piece of paper below, if the tin sheet fully covered the window? With the model as a mediator, in a later conversation, Isufi explains in detail how the tin sheet was not attached at the bottom, but tilted in an angle and fastened by screws along its sides. Nearly 45 years later, this memory resurfaces with certainty, and a later visit to the site confirms the remaining screw holes on the window sides. The model, therefore, does not merely represent the cell. It questions, clarifies, and reconstructs reality, revealing details that would otherwise remain overlooked.

In the preface of Letters from Prison: The Censored Book – a collection of letters from political prisoners in Kosovo – Merxhan Avdyli notes that, while the book will in no doubt leave a heavy mark on its reader, this was never the intention of the letters’ original authors. What is quite evident here, is that the spatial information we derive from these sources gives an account of the prison so direct that makes them almost incomparable to conventional architectural documentation. Thus, this exploration calls for an expanded understanding of evidence in the field of architectural history. Smuggled letters, secret poems and whispered messages — often overlooked as spatial evidence — begin to map carceral spaces in ways that defy conventional understandings of prisons as total institutions. Each narrative unfolds spatially –speaking of doors, windows, walls and floors — but also temporally — structuring events, waiting, mapping movement and resistance. However, both spatially and temporally, they remain bound to the human scale, written by and for humans. It is only in combination with architectural documents that we reach the non-human scale to discover the prisons’ own narrativity in its ability to evoke stories.

The production of architectural documents, such as maps, plans, sections and models, serves both as a process and a tool through which to uncover spatial dynamics. Each document, in its own dimension, abstracts certain aspects of the building that would otherwise remain undiscovered. Maps reveal broader spatial connections highlighting proximities and boundaries; plans allow us to investigate internal organizations; sections expose vertical relationships, and finally, models bring structures into three-dimensional forms, making spatial dynamics even more palpable. In the case of the Gjilan prison, these documents reveal the alternate uses of the prison infrastructure — the door becomes a torturing instrument, the window a shield for secret exchange, and the wall a conduit for communication. In doing so, these documents do not merely describe space, but they continuously produce and transform it.

Through rethinking the limits of architectural evidence and unveiling the generative role of architectural documents, this paper calls for a more liberated field of study, not only in regard to history, but also in rethinking how we engage with the present — in heritage and in writing architecture. Moreover, through these two contributions, the relevance of this paper extends beyond the field of architectural history. First, it engages with Narrative Theory by examining how narratives and storytelling can intersect with architectural documents. It is through this dialogue that spatial relationships first become apparent. Second, it contributes to discussions on the prison boundary within the field of Carceral Geography, by spatially unveiling the tangible and intangible flows that penetrate physical borders. While Hilde Heynen notes that contemporary architectural research is marked by a growing interdisciplinarity, she also marks it crucial to keep maintaining the core questions that define the discipline's identity, namely:

the discipline’s focus on the spatial and material characteristics of buildings — their plans and sections, their integration into context, the way they enable or guide movement, and their practical as well as symbolical values.

Accordingly, this research places architectural documents at its center, treating them as primary tools for the disclosure of overlooked information. Overall, in its layered content, this paper does not aim to construct an unambiguous and objective architectural history of a building. Rather, it embraces the subjectivity inherent in oral history and experience, highlighting spatial discoveries and creating space for multiple readings to emerge.

notes

For an overview of Kosovo’s status within Yugoslavia and the increasing repression of Kosovo Albanians from the 1980s until the start of the war in 1998, see: Judah, Tim. 2000. Kosovo: War and Revenge. New Haven: Yale University Press. See also: Malcolm, Noel. 1998. Kosovo: A Short History. New York: New York University Press. For a human rights perspective covering the war period, consult: Human Rights Watch. 2001. Under Orders: War Crimes in Kosovo. New York: Human Rights Watch. As there is an abundance of studies on the breakup of Yugoslavia, an overview of key scholarly debates can be found in: Ramet, Sabrina Petra. 2005. Thinking about Yugoslavia: Scholarly Debates about the Yugoslav Breakup and the Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

For an examination of shifts in architectural evidence, see: Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative, 2021. Writing Architectural History: Evidence and Narrative in the Twenty-First Century. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. For perspectives on oral history as evidence, see: Gosseye, Janina, Naomi Stead and Deborah Van der Plaat, eds. 2019. Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, as well as: Akcan, Esra. 2018. Open Architecture. Migration, Citizenship and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA 1984/87. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Evans, Robin. 1997. Translations from Drawing to Building. Cambridge: MIT Press, 154.

For more information on the spatial dynamics of incarceration, see: Moran, Dominique. 2015. Carceral Geography: Spaces and Practices of Incarceration. Farnham: Ashgate.

For a thorough study on literature approaches to architecture, see: Havik, Klaske. 2014. Urban Literacy: Reading and Writing Architecture. Rotterdam: nai010. For a more specific view on narratives, see: Bernal, Dalia Milián and Carlos Machado e Moura. 2023. “Unearthing Urban Narratives Towards a Repository of Methods.” In Writing Urban Places. New Narratives for the European City, edited by Klaske Havik et al., 53-72. Rotterdam: nai010.

While each element in this constructed narrative is taken from the original accounts of political prisoners in Kosovo, they occurred separately in different prisons and at different times. Their original contexts are then discussed in the following chapters.

This exploration of the Prison of Gjilan is part of a larger PhD project titled In Space We Read Trauma: Disclosing Microhistories in Kosovo, 1980-1999, funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) and supervised by Prof. Rajesh Heynickx and Prof. Gisèle Gantois. The project investigates the complex relationship between traumatic experiences and space. Thus, the methodology elaborated in this paper is neither limited to nor focused on prison architecture. For this reason, it does not primarily engage with established literature within prison studies.

The first interview was conducted in 2021 as part of my master’s thesis To Meet Galileo on Day Fourteen. An Eclectic Architectural Documentary: The Case of Gjilan Prison at KU Leuven, within the 'Incipient Raum' studio with Tomas Ooms. Although focused differently, its initial findings laid the groundwork for this PhD project. In 2023 and 2024, six additional former political prisoners were interviewed. Those interviewed during this research were contacted based on prior acquaintance and through the Association of Political Prisoners of Kosovo (Shoqata e të Burgosurve Politikë të Kosovës). While it was important to integrate different actors and perspectives, only one former prison guard agreed to be informally interviewed, providing very limited information on the proportions and lighting of prison offices. The research has been reviewed and approved by KU Leuven’s privacy and ethics committee (PRET), ensuring that participants’ privacy and consent are handled with the utmost care and confidentiality.

Author's translation. Original poem from the private archive of Ahmet Isufi: "Në dhomën trembëdhjetë, ngjyrë e përhimtë, mbi plagët e mia. Shiu i ditës së trembëdhjetë, mbi llamarinë, plumb mbi ëndërrat e mia. Unë me trembëdhjetë udhëtarë, sillemi rrathëve të ferrit, për ta takuar Galileun, në ditën e katërmbëdhjetë."

Author's translation. Original letter: “Këtu, është interesant se për çdo mëngjes, nëse zgjohesh herët, derisa nuk zgjohen të burgosurit e tjerë, me të madhe dëgjohet zhurma e përzier e shpezëve: cicërrima e harabelave dhe e vremçave të tjerë, krrokatja e sorrave dhe e korbave, si dhe kënga e vaji i kumrijave […]” See Avdyli, Merxhan and Bajram Kosumi. 2004. Letra nga Burgu. Libri i Censuruar[Letters from Prison. The Censored Book]. Pristina: Brezi'81, 307.

Interview with Teuta Hadri, conducted by the author. Pristina, April 2024.

Underground movements and political imprisonments were widespread in the region since the early post–World War II period. However, this paper focuses primarily on the 1981 protests which emerged in response to the systemic repression of Kosovo Albanians under socialist Yugoslavia. For a detailed account of the 1981 protests, see Noel Malcolm’s Kosovo: A Short History, particularly the chapter “Kosovo after the death of Tito: 1981-1997.” Many of the activists involved in these protests, including those discussed in this paper, were affiliated with various underground groups operating under the broader movement known as Ilegalja. Due to its clandestine nature, Ilegalja’s history remains relatively dispersed. For insights, consult: Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie. 2011. “The bequest of Ilegalja: contested memories and moralities in contemporary Kosovo.” In Nationalities Papers 41(6). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 953–970. For a feminist perspective, refer to: Krasniqi, Elife. 2011. “Ilegalja: Women in the Albanian underground resistance movement in Kosovo.” In Profemina, 2. 99-114. The complex evolution of the Ilegalja movement, from the 1960s until today, is evident in a recent study that traces the origins of the Kosovo Liberation Army and its eventual transformation into the Army of the Republic of Kosovo. For more details, read: Muharremi, Robert, and Alisa Ramadani. 2024. Transforming a Guerilla into a Regular Army: From the Kosovo Liberation Army to the Army of the Republic of Kosovo. Cham: Springer.

Malcolm, Noel. 1998. Kosovo. A Short History. New York: New York University Press, 349. Malcolm writes: “Most Albanian doctors and health workers were also dismissed from the hospitals; deaths from diseases such as measles and polio have increased, with the decline in the number of Albanians receiving vaccinations. Approximately 6,000 school-teachers were sacked in 1990 for having taken part in protests, and the rest were dismissed when they refused to comply with a new Serbian curriculum that largely eliminated the teaching of Albanian literature and history. In some places the Albanian teachers were allowed to continue to take classes (without state pay) in the school buildings, but strict physical segregation was introduced - with, for example, separate lavatories for Albanian and Serb children - and equipment or materials, including in one case the window-glass, was removed from the areas they used. [...] Arbitrary arrest and police violence have become routine. Serbian law allows the arrest and summary imprisonment for up to two months of anyone who has committed a 'verbal crime' such as insulting the 'patriotic feelings' of Serbian citizens. It also permits a procedure known as 'informative talks', under which a person can be summoned to a police station and questioned for up to three days: in 1994 15,000 people in Kosovo were questioned in this way, usually without being told the reason for the summons. Serbian law does not, of course, permit the beating up of people in police custody; but many graphic testimonies exist of severe beatings with truncheons, the application of electric shocks to the genitals, and so on. Also widely violated in Kosovo are the official rules for the lawful search of people's houses: homes are frequently raided without explanation, and goods and money confiscated (i.e. stolen) by the police. In 1994 alone the Council for the Defence of Human Rights and Freedoms in Kosovo recorded 2,157 physical assaults by the police, 3,553 raids on private dwellings and 2,963 arbitrary arrests.”

Benjamin, Walter. 1969. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Random house. 83-109.

Interview with Teuta Hadri, conducted by the author. Pristina, April 2024.

Interview with Ramadan Dermaku, conducted by the author. Pristina, March 2024.

Avdyli, Merxhan et al. 1991. Libri i Lirisë [The Book of Freedom]. Pristina: Rilindja.

Kosumi, Bajram. 2020. Letërsia nga Burgu: Kapitull më vete në letërsinë shqipe [Prison Literature. A chapter on its own in Albanian literature]. Skopje: ITSHKSH, 66-67.

Ibid.

Hajrizi, Mehmet. 2021. Korrespodencë nën Censurë [Correspondence in Censorship]. Tetovo: Syth.

Kosumi, Bajram. 2020. Letërsia nga Burgu: Kapitull më vete në letërsinë shqipe. [Prison Literature. A chapter on its own in Albanian literature]. Skopje: ITSHKSH, 254.

Author's translation. Original letter: “E mira e babit, po të shkruaj pa kurrfarë shprese se do ta marrësh këtë letër, sepse si duket këtu nuk i lejojnë letrat e shkruara në gjuhën shqipe, edhe pse këtë nuk e thonë hapur. [...] Të kesh kujdes cuca e babit, të shkruash pa bërë ilustrime e vizatime, kështu siç ta kam shkruar këtë letër” in Avdyli, Merxhan and Bajram Kosumi. 2004. Letra nga Burgu. Libri I Censuruar [Letters from Prison. The Censored Book]. Pristina: Brezi'81, 52-53.

In an interview I conducted with Ahmet Isufi, he recounts the protocol in which every prisoner was required to stand and face away from the door each time the guard entered the room.

Interview with Selajdin Abdullahu, conducted by the author. Pristina, March 2024.

Interview with Ahmet Isufi, conducted by the author. Pristina, October 2021.

Heynen, Hilde. 2024. "Architectural History Today: Where Do We Stand? Where Do We Go?.” In Perspectives in Architecture and Urbanism, 1(1), 100005.

Simone Barbi

Gianfranco Orsenigo

Giorgia Strano

Eliana Martinelli