The Alami Farm School, founded in 1949 in Jericho by Palestinian leader Musa Alami, was an agricultural school that served as both a refuge and an educational institution for Palestinian refugee children displaced by the Nakba—the mass displacement of Palestinians during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Transforming the arid land of the Jordan Valley—then part of Palestine under Jordanian administration—into a thriving agricultural and educational environment, the Alami Farm School modelled a regenerative approach to the impermanent, aid-dependent structures of typical refugee camps. Refugees at the school actively participated in land restoration, developing skills in sustainable farming, water management, and ecological care. This hands-on approach enabled them to reclaim both knowledge and autonomy, embodying a decolonial ethos that positioned them as active participants rather than passive recipients of aid.

Rather than reinforcing dependency, the Alami Farm School empowered students to revitalize their environment, integrating cultural identity with environmental stewardship. Its regenerative model countered extractive systems that had historically depleted resources and disrupted traditional ecological knowledge, instead fostering a self-sustaining relationship with the land. Alami’s vision prioritised reintegration and resilience, strengthening both community cohesion and ecological sustainability.

Drawing on newly examined archival materials, this paper examines the architectural, pedagogical, and ecological strategies of the Alami Farm School, highlighting its significance in refugee settlement design.

The school’s architecture reflected this philosophy, being constructed from locally sourced materials and designed to serve both educational and agricultural functions. Its structures harmonised with the surrounding landscape, countering colonial legacies of environmental degradation and nurturing a symbiotic connection between people and place.

As climate-driven displacement accelerates globally, the Alami Farm School’s approach offers a compelling model for refugee spaces. In a time when displacement is increasingly long-term, the school’s legacy challenges contemporary refugee policies, advocating for regenerative, not extractive, refugee settlements that foster autonomy, ecological restoration, and community resilience. Even within the constraints of displacement, the Alami Farm School demonstrates the possibility of cultivating rootedness, resilience, and sustainable development, presenting a vision for humanitarian architecture in a world facing escalating climate and displacement crises. Its relevance is amplified by contemporary humanitarian and environmental crises.

The Alami Farm School, founded in 1949 by Palestinian leader Musa Alami, represented a remarkable intervention in the aftermath of the Nakba – the forced displacement of Palestinians during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. As over 700,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled from their homes, humanitarian efforts focused on temporary relief rather than long-term solutions. Refugee camps, set up at that time under the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), became spaces of waiting rather than reconstruction, reinforcing aid dependency and political exclusion1.

In contrast, the Alami Farm School redefined the refugee experience – not as a condition of passivity but as an opportunity for self-sufficiency, environmental restoration, and economic renewal. Situated on two thousand acres of arid land in the Jordan Valley, the school functioned as both an agricultural training centre and a model village, where displaced Palestinian youth could learn to cultivate the land, reclaim economic independence, and envision a self-sufficient future 2,3.

At its core, the school was an experiment in architecture, pedagogy, and resistance, offering a material alternative to the spatial confinement of UNRWA refugee camps. Through regenerative architecture, hands-on agricultural training, and self-reliant communal living, it sought to prove that Palestinian displacement could be transformed into an act of restoration. This paper explores the historical, architectural, and pedagogical significance of the Alami Farm School, positioning it within broader debates on decolonial education, environmental resilience, and the politics of refugee architecture4,5 (fig. 1).

The Nakba was not only a mass exodus but an act of erasure – a campaign that dismantled Palestinian space and dislocated rural life. Entire villages were destroyed, farmlands seized, and local economies systematically disrupted6. The establishment of the State of Israel led to the systematic depopulation of over five hundred Palestinian villages, many of which were transformed into Israeli settlements or military zones7 (fig. 2).

In the wake of this destruction, UNRWA was established to manage the refugee crisis. However, rather than facilitating resettlement or long-term economic independence, UNRWA-administered camps functioned as containment spaces, where refugees received minimal provisions, including basic rations, makeshift shelters, and limited infrastructure8. Though initially intended as temporary relief, this system became a permanent mechanism of statelessness, in which Palestinians remained geographically displaced and politically marginalised (fig. 3).

Musa Alami, one of Palestine’s most influential intellectuals, criticised this architecture of dependency. In 1949, he founded the Arab Development Society (ADS), securing Jordanian state backing and international funding to establish a self-sufficient refugee training centre in Jericho. His vision was to create a training centre for Palestinian orphans where modern agriculture would serve as a tool for rehabilitation and renewal. On the outskirts of Jericho, a landscape thought to be agriculturally unviable became a site of pedagogical and ecological experimentation9,10 (fig. 4).

While radical in its rejection of aid dependency, the ADS was also implicated in the era’s developmentalist ethos. It relied on funding from organisations such as the Ford Foundation, Oxfam, and the World Bank – entities often associated with Western agendas of modernisation. This paradox reveals the dual identity of the Alami Farm School – both a radical rejection of refugee dependency and a product of cold war-era development economies11,12.

The built environment of the Alami Farm School was central to its pedagogical vision. In contrast to the rigid, grid-like structures of UNRWA camps, which were designed for administrative efficiency rather than autonomy, the school was conceived as a living laboratory for regenerative architecture13.

Rather than relying on prefabricated shelters or concrete structures with little regard for environmental context, the Alami Farm School’s material and spatial choices were deeply intentional. Housing units were constructed from sun-dried mud bricks, produced on-site, which ensured both durability and insulation while symbolically preserving pre-colonial Palestinian construction traditions14 (fig. 5). The school's architecture blended with the surrounding landscape, mitigating the sense of alienation often associated with prefabricated refugee housing15. The spatial arrangement followed vernacular logics, interweaving communal and agricultural functions rather than separating them16.

Even the site selection – a rocky, arid edge of the Jordan Valley – was significant. It was a deliberate act of reclamation, demonstrating how ecological knowledge and collective labour could rehabilitate “unusable” land17. Each housing unit included a small garden cultivated by students, producing food for communal meals and reinforcing principles of cooperative responsibility and sustainability.

Key architectural features of the school reflected its commitment to pedagogy, the environment, and community integration. The locally produced materials reinforced the school's ethos of self-reliance, minimizing dependency on external resources. The classrooms opened directly onto agricultural fields, allowing students to transition between theoretical instruction and hands-on training18. Communal living was also central to the school's architectural vision. Collective housing units were deliberately designed to foster social resilience, offering an alternative to the nuclear family model that was more typical of Palestinian village life19. Vocational training, such as textile, carpentry or construction workshops, played a key role in equipping students with practical skills to maintain and expand these living spaces (fig. 6). These spaces encouraged cooperation and shared responsibilities, mirroring the broader philosophy of regenerative education and settlement.

Daily life at the Alami Farm School extended beyond agricultural training and labour – it fostered a sense of belonging and normality. Students swam, cared for animals, and shared meals they helped grow. (figg. 7 and 8). The presence of animals, gardens, and recreational activities underscored the school’s holistic approach to education, in which emotional well-being was valued alongside vocational training. By creating shared experiences and a structured daily rhythm, the school allowed students to grow up as part of a supportive community rather than merely receiving aid20.

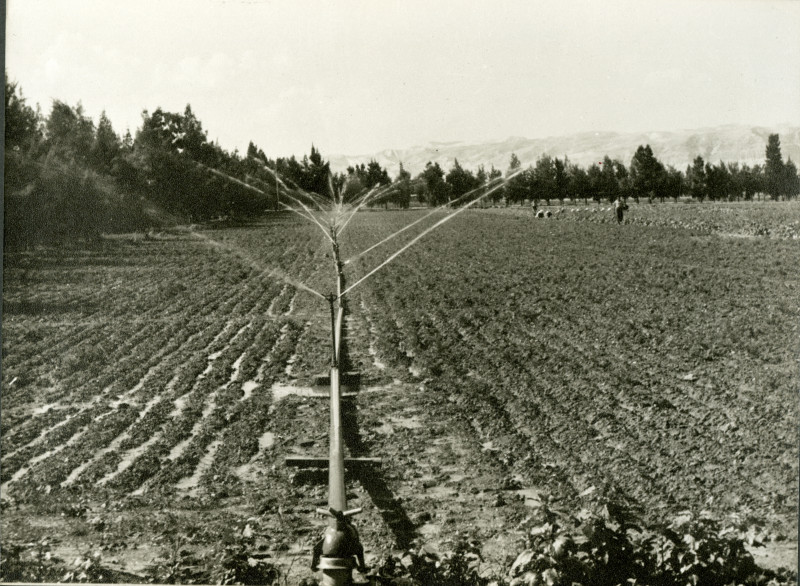

The school’s irrigation systems not only demonstrated the Jordan Valley’s agricultural potential – challenging Western assessments of the region as unviable – but also served as a pedagogical tool where students learned hydrological techniques, soil conservation, and sustainable water management21 (fig. 9). Housing and learning spaces were not discrete entities but interconnected, ensuring that students were fully immersed in the daily rhythms of land cultivation22. Classrooms opened directly onto fields, with movable partitions allowing for seamless transitions between indoor and outdoor learning spaces, reinforcing the integration of theoretical and applied knowledge23 (fig. 10). Each residential unit, home to ten students, maintained its own garden, where boys cultivated crops together as part of their daily routine24. This agricultural engagement extended beyond the practical – through cultivating the land, students developed a deep sense of stewardship, understanding their role not only as learners but as active participants in shaping their environment. The gardens also symbolised a broader philosophy: that displaced communities could sustain themselves through regenerative practices, transforming landscapes while reclaiming agency over their livelihoods25. This approach anticipated contemporary biophilic design principles, where built environments are designed to cultivate ecological awareness and engagement26.

The central irrigation system was not merely an infrastructural feature but also a pedagogical tool, where students participated in hydrological experiments, soil conservation techniques, and sustainable water management, acquiring hands-on knowledge crucial for farming in arid conditions27.

The school’s architectural philosophy contrasted with both traditional Palestinian village layouts, which were rooted in kinship networks, and Israeli kibbutzim, which functioned as state-sponsored agrarian collectives. The Alami Farm School occupied an ambiguous position between community-building and developmentalist planning28.

The philosophy behind the school’s spatial design can be understood as a counter-colonial spatial strategy, asserting permanence in the face of enforced displacement. By creating a landscape capable of regenerating itself over time, the school subverted the dominant model of refugee settlements, which typically relied on precarious, short-term shelter solutions29,30. In many refugee camps of the time, architecture functioned as an instrument of containment rather than a catalyst for development, reinforcing the notion that displacement was a passive condition to be endured rather than actively overcome. The Alami Farm School rejected this premise, demonstrating that refugee communities could actively shape their environment, reclaiming agency over both built space and agricultural landscapes31,32.

Yet the physical resilience of the school could not shield it from political violence. Following Israel’s occupation of the West Bank in 1967, the Israeli military dismantled its irrigation systems, effectively erasing its capacity for self-sufficiency33. This act was not isolated – it formed part of a wider strategy aimed at undermining Palestinian agricultural autonomy.

Throughout the occupied territories, agricultural landscapes have been deliberately targeted as a form of environmental warfare. The systematic razing of farmlands, water wells, and cooperatives has served as a mechanism of geopolitical control, ensuring that Palestinian communities remain dependent on external food markets rather than achieving economic sovereignty34,35.

The dismantling of the school’s self-sustaining infrastructure was not incidental but strategic. It aligned with broader Israeli policies restricting Palestinian access to water, constraining agricultural output, and obstructing efforts to rebuild independent farming systems36.

Ultimately, this destruction was not merely an attack on the school itself but an effort to erase the possibility of alternative Palestinian futures—where displaced communities might sustain themselves beyond the imposed structures of humanitarian aid and military occupation37,38.

Today, as climate change displaces millions, Alami Farm School – better known as the Arab Development Society – offers an urgent alternative to conventional refugee policy frameworks. Unlike United Nations-administered camps of its time, which relied on external aid and non-sustainable materials, the school modelled a self-sufficient, regenerative approach to displacement39.

Modern refugee settlements remain dependent on international aid and humanitarian infrastructure. However, as climate-induced displacement accelerates, there is growing recognition that long-term refugee spaces must prioritise ecological sustainability40.

The Alami model – centred on self-sufficiency, land regeneration, and participatory settlement planning – offers a critical framework for rethinking refugee architecture41. Rather than treating displacement solely as a humanitarian crisis, its legacy challenges policymakers to view refugees as active agents of environmental restoration42. In an era where forced migration is increasingly long-term and systemic, the Alami Farm School remains a provocative alternative, urging us to design refugee spaces not as sites of containment but as landscapes of renewal43.

The pedagogical and ecological principles tested at the Alami Farm School have not disappeared. In recent years, experimental schools such as the ARCò-designed Primary School in Al Khan Al Ahmar (Jerusalem periphery), and the Earth-Bag School in Um al Nasser (Gaza Strip), co-designed by ARCò and MCA, have echoed similar commitments to local materials, community autonomy, and regenerative construction. These projects, like Alami’s, emerge in landscapes of restriction and displacement – yet imagine new educational and environmental futures through architecture44,45.

In light of the ongoing humanitarian catastrophe in Palestine, the legacy of such models becomes even more urgent. They not only demonstrate design resilience but challenge dominant paradigms of humanitarian aid, positioning refugee communities as stewards of their environments, even under occupation46,47.

notes

Feldman, Ilana. 2008. Governing Gaza: Bureaucracy, Authority, and the Work of Rule, 1917–67. Durham: Duke University Press. For UNRWA’s founding mandate and evolution as a permanent humanitarian institution.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2023. “The Dilemmas of Local Development and Palestine Refugee Integration in Jordan: UNRWA and the Arab Development Society in Jericho (1950–80).” Jerusalem Quarterly 93. Detailed study comparing UNRWA’s relief model with the ADS.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2023. “Forgotten History: A Vision for Palestinian Refugees’ Agricultural Self-Sufficiency.” The Architectural Review, October 30. Describes Alami’s land acquisition and the nationalist framing of agricultural rehabilitation.

Tan, Pelin. 2022. “An Agricultural School as a Pedagogical Experiment.” In Radical Pedagogies, edited by Beatriz Colomina et al. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Discusses the integration of technical education and local knowledge at the school.

Bosch, Susanne. 2017. Alter-Nationality: 4 Aphorisms. Reflects on spatial autonomy in refugee settlements through examples like the Alami Farm School.

Khalidi, Walid. 1992. All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies. Foundational documentation of village erasure following the Nakba.

Masalha, Nur. 1992. The Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of "Transfer" in Zionist Political Thought, 1882–1948. Institute for Palestine Studies. Provides ideological and strategic context to village destruction.

Feldman, Ilana. 2018. Life Lived in Relief: Humanitarian Predicaments and Palestinian Refugee Politics. University of California Press. Explores the everyday implications of UNRWA aid mechanisms.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2000. “The Arab Development Society: Vocational Training and the Struggles of Palestinian Self-Sufficiency.” Middle East Journal 54, no. 2: 251–275. Outlines Alami’s plans, political support, and training methodology.

Khalidi, Rashid. 1997. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. Columbia University Press. Situates the ADS in wider debates on exile, return, and identity.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2021. “Consolidating the Rule of Experts: A Model Village for Refugees in the Jordan Valley, 1945–55.” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 10, no. 2: 361–391. Frames ADS within Cold War developmental politics.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2000. Op. cit.; see also Miracle in the Holy Land, Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford. Archival sources documenting ADS infrastructure and external funders.

Bosch, Susanne. 2017. Op. cit.

Near East News Association. 1953. The Arab Development Society’s Jordan Valley Project. Beirut: Near East News Association.

Ibid.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2000. Op. cit., 251–275.

Tan, Pelin, and Dima Yaser. 2022. Designing Modernity: Architecture in the Arab World 1945–1973, edited by George Arbid and Philipp Oswalt, 149. Berlin: Jovis Verlag.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Penguin Books.

Khalidi, Rashid. 1997. Op. cit.

Near East News Association. 1953. Op. cit.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2023. Op. cit.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2023. Op. cit.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Penguin Books.

Near East News Association. 1953. Op. cit.

Ibid.

Harrell-Bond, Barbara. 1986. Imposing Aid: Emergency Assistance to Refugees. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 214.

Weizman, Eyal. 2007. Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso.

Bosch, Susanne. 2017. Op. cit.

Tan, Pelin and Dima Yaser. 2022. Op. cit., 152.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2023. Op. cit.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2023. Op. cit.

Khalidi, Rashid. 1997. Op. cit.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2023. Op. cit.

Weizman, Eyal. 2007. Op. cit.

Harrell-Bond, Barbara. 1986. Op. cit., 214.

Tan, Pelin and Dima Yaser. 2022. Op. cit., 149.

Al Husseini, Jalal. 2000. Op. cit.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2021. Op. cit., 361–391.

Chatty, Dawn. 2010. Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ADS serves as a precedent for regenerative, land-based refugee settlements that foreground ecological recovery.

Betts, Alexander et al. 2017. Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System. New York: Penguin. Current settlements in Jordan, Lebanon, and Bangladesh exemplify containment models that fail to integrate ecological resilience.

Galtung, Johan. 1977. Development, Environment and Peace. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute. Early argument for integrated, sustainable design in contexts of displacement.

Abusaada, Nadi. 2021. Op. cit., 361–391. Reviews the structural dismantling of self-sustaining models in favor of aid dependency.

Harrell-Bond, Barbara. 1986. Op. cit., 214. The Alami model challenges prevailing aid-based governance, advocating for refugee agency and autonomy.

ARCò Architecture and Cooperation, Primary School in Al Khan Al Ahmar, project summary, 2015. Designed to serve the Jahalin Bedouin community under threat of demolition, the school employed sustainable building methods adapted to a militarized landscape.

MCA Architects and Vento di Terra NGO, Earth-Bag School in Um al Nasser, Gaza Strip (2011–2014). Built with local labour and earth-bag techniques to reinforce spatial autonomy in a context of economic blockade.

UN OCHA. 2023. “Education Under Threat in the West Bank and Gaza,” Humanitarian Bulletin. Documents the systematic demolition of Palestinian learning spaces by Israeli authorities, including schools using sustainable materials.

UNRWA. 2025. “Situation Report #171 on the Humanitarian Crisis in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem,” May 16.

Anna Veronese

Tara Bissett

Edited by: Elisa Boeri (Politecnico di Milano), Luca Cardani (Politecnico di Milano) and Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano)

Fabio Gigone